Facebook: Next stop Europe

The Düsseldorf Higher Regional Court on Wednesday added a new twist to the Bundeskartellamt vs. Facebook saga: The case is going to Luxembourg to the European Court of Justice. Meanwhile, as of today, 24 March 2021, it remains open whether the Bundeskartellamt will have Facebook’s implementation plan submitted to it in the meantime. Rupprecht Podszun was at the hearing in the Düsseldorf Higher Regional Court for D’Kart.

As I stumbled out of the Higher Regional Court, out into the open, the sun was shining, I briefly took off my mask for a breath of fresh air, the Rhine was rolling with some momentum towards the North Sea – I met a well-known Düsseldorf antitrust lawyer whom I had not seen in the courtroom. Put the mask back on. Oh, he was with the beer cartel. True, that was running in parallel to the most exciting, most spectacular, most important antitrust case of the last few years, decades. (And if you forget about the beer cartel, which is quite juicy, that’s saying something).

The lawyer asked briefly how it went before he had to rush on and I said: The Facebook case is going to the ECJ. The expression on his face was priceless. It virtually summed up everything that had unfolded in terms of emotionality, irritation, enormous intellectual effort, theatricality and, ultimately, perplexity over several hours in Room A01 in the basement of the Düsseldorf Oberlandesgericht (OLG), the Higher Regional Court.

A Senate in line?

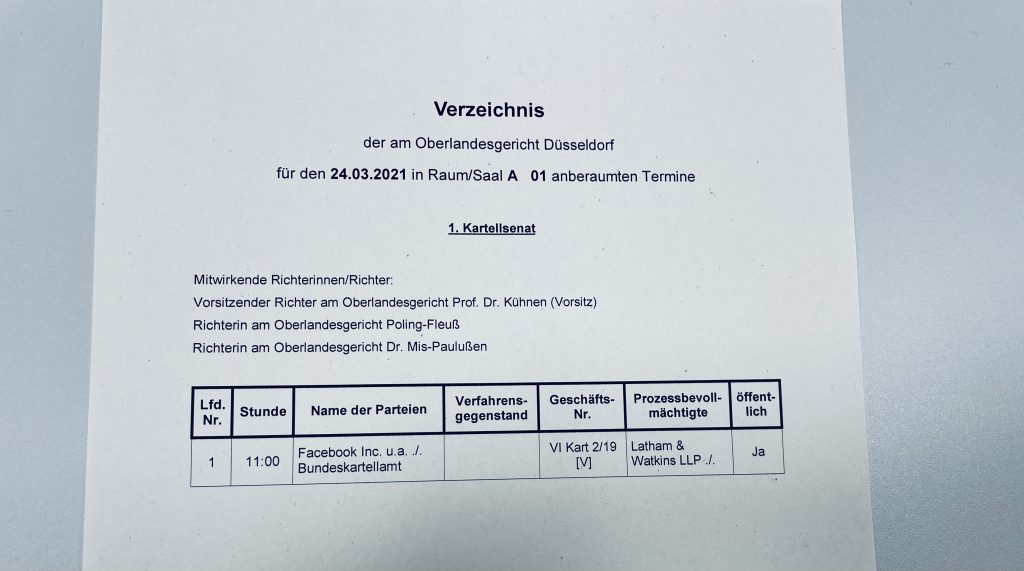

Actually, everything was clear: On 24 March 2021, 11.00 a.m., the case Facebook Inc. et al. (the “et al.” will still have to be discussed) v. Bundeskartellamt was called. The case was chaired by Prof. Dr. Jürgen Kühnen. The case has a history: in 2016, the Bundeskartellamt (Federal Cartel Office, FCO) initiated proceedings against Facebook, and in 2019 it made a decision that, in its remedies, aims at the heart of Facebook’s business model. A shuttling between Düsseldorf and Karlsruhe followed: Kühnen’s senate ordered suspensive effect in the interim proceedings, thereby helping Facebook. The Bundesgerichtshof (BGH), the Federal Supreme Court, overturned this decision. However, it was not enforced; a rather strange interlude prevented this for the time being. (You can read all the details, including numerous references, on our new service page https://www.d-kart.de/der-fall-facebook/, which I compiled with students from my antitrust class).

Anyone who had read the summary decision of the OLG could have no doubt that there would be little to gain for Jörg Nothdurft and the team from the Federal Cartel Office (Irene Sewczyk, Gunnar Pampel and Stephan Schweikardt). In the summary proceedings, the court had already criticised so many deficiencies that it would have been a surprise if the Bundeskartellamt had taken victory today in the main proceedings. Having said that – after all, the BGH had dealt with the case in the meantime and made detailed statements. Would the Senate follow the BGH line?

Closer observers would probably take such a question as a joke. The different opinions of the two senates are well-documented and well-known – examples from today later. However, it should also be borne in mind that Kühnen had two new judges at his side compared to the summary proceedings – Alexandra Poling-Fleuß and Ursula Mis-Paulußen. They deviated slightly from the line Kühnen had set out with their predecessors in the summary proceedings, Lars Lingrün and Andrea Lohse.

For those who doubt whether a court lower in the pecking order of the judiciary, such as the OLG, can take a different view from what the BGH had said: Yes, of course. Judges are independent. That’s the whole thing about judges. The OLG is neither factually nor legally bound by the BGH. Judge Kühnen: “It is the official duty of the members of the Senate to determine the factual and legal situation themselves.” And he added: Whoever thinks we would just fall in line with the BGH is probably insinuating that we are violating our official duties. You better think twice.

Corona-style class reunion

The hearing, a highlight of the face-to-face events in this year’s thinned-out antitrust calendar, had a bit of a scaled-down Corona-style class reunion about it: Facebook now has three law firms: Latham Watkins (Michael Esser, Jan Höft, Judith Jacop), Gleiss Lutz (Ingo Brinker, Ines Bodenstein) and WilmerHale (Hans-Georg Kamann). Esser sinks into his inner self before the trial begins, while the Facebook representatives around him chatter somewhat excitedly – that’s probably the way it is when you work in a chatterbox corporation (Facebook, Whatsapp, Instagram). Ingo Brinker from Gleiss Lutz, advisor in the background, seemed – as usual – calm and was even able to have a short chat with economist Doris Hildebrandt, who – at a distance – was sitting next to him. The consumer advocates from the Federation of German Consumer Organisations (VZBV) were parties to the proceedings, too. Appropriately, the small tables for Heiko Dünkel, their chief litigator, and lawyer Sebastian Louven were placed on the side of the FCO. Dr Louven’s name badge was emblazoned with a still quite fresh doctorate.

Speaking of doctoral theses. Or, no, I’ll write that down later, let’s walk the halls first. The Cartel Office, as written, is represented by four people, led by Nothdurft. When you know that there are only three people in a decision-making department who are responsible for this mega case, you may of course start to wonder whether such an authority is still on a par with the most powerful companies in the world.

At a measured distance: the media and the public. The prudent press officer of the Higher Regional Court, Dr Michael Börsch, had the delicate task of managing the expected crowd in a small courtroom in times of a pandemic, and he solved it to general and definitely my satisfaction: D’Kart sat in a row with journalistic icons dpa and Süddeutsche Zeitung, which, as the readers of this blog may well concede, is at least appropriate. In the cheap remaining seats: More Facebook lawyers and observers who eagerly took notes. Those who couldn’t find a seat here were directed to another room where the hearing was broadcast with sound. Some of my students were sitting there, and for them it was an ambivalent foretaste: they will enter this room again for taking their final exams.

The goals of abuse control

Judge Kühnen, focused, calm, not a sip of water the whole time, opened the hearing – after the usual Corona references – with a 90-minute presentation of how he and the two wing judges provisionally assess the case.

The very first major point of the proceedings was a fundamental consideration, the significance of which was not quite apparent. Why did the Office not apply Article 102 TFEU? The Senate was puzzled. Cartel Office: Because in German law the violation by general terms and conditions is already much clearer than in EU law. So. Is Section 19 of the German act GWB stricter than Article 102 TFEU? The Senate takes the view that Section 19 GWB and Article 102 TFEU, the two prohibitions of abuse, are essentially the same. I tend to say that in my lectures. Jörg Nothdurft, on the other hand, an expert on Section 19 of the German act, as a very prominent publication of his in a book called Langen/Bunte proves, explained that Section 19 has a completely different “canon of objectives” than its European counterpart. That was interesting, and I hoped my students would take notes at that moment on the meaning and purpose of German and European abuse control. But as is so often the case when things get particularly gripping academically, the practical benefits remained manageable: it was rather unlikely (and so it did not happen) that Facebook would also ask for a slap on the wrist based on Art. 102 TFEU.

The GDPR is back in play

The second major step in Kühnen’s presentation, however, was very much to the point. He opened the point with a clear statement:

“In principle, an abuse of market power can be brought about by a breach of consumer protection law standards. “

This opens the door to a violation of competition law due to a breach of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). In doing so, the Senate basically recognised the test it had read out of the Cartel Office’s decision. The fact that the BGH structured the case differently did not bother the Senate any further – it had to decide on the Cartel Office’s order. The fact that the FCO would probably not put it that way either still became an issue. Two big buts are attached to this “abuse through breach of law”-theory: Does the FCO even have jurisdiction for dealing with GDPR violations? And if so, is Facebook in breach of the GDPR?

You may stop reading at this point, because the (abstracted) answers will hopefully be given by the European Court of Justice within the next aeons years. But then you would not learn anything more about the value of science, and about some quite remarkable sentences we heard today.

An Irish brew over competence

The Senate has considerable doubts as to whether a competition authority may “ultimately, in the end, act as a data protection authority”. So is the GDPR enforcement framework assigning competencies? If yes, the Irish data protection body (I hesitate to call it an authority in the field) would probably be responsible. To my knowledge, they are doing about as well with privacy enforcement as Germany is with testing, vaccination and contact tracing. However, rules on jurisdiction are not designed in such a way that someone else can simply step in if others have vacated the place. Nothdurft’s remark to this effect (the Irish don’t do anything, so we’re allowed to!) was dryly commented on by Kühnen as a “bold statement”.

The crux, however, lies in the words “ultimately, in the end”. Yes: If the Cartel Office is successful, this would be a considerable blow to Facebook’s building of super profiles by combining all possible data. But: did the office apply the GDPR here? Or did it only (according to the reading preferred in Bonn and Karlsruhe ) use the value judgments of the GDPR to justify or illustrate a violation of antitrust law? Is this a problem of economic power (i.e. antitrust law) that is mirrored in too intensive data processing? Or is it about the overly intensive data processing itself (i.e. privacy law)?

As I understand it, the OLG will submit the question of whether the Bundeskartellamt is inadmissibly interfering with an (allegedly) definite framework of jurisdiction, provided for by the GDPR. But I am not sure to that one hundred percent, since it happened very quickly when Kühnen revealed shortly before the end of the hearing day that they intended to refer the case to the ECJ.

Material for Luxembourg from the D-Court (and D is for data)

On the question of an infringement by Facebook, the court also noticed some ambiguities in the GDPR. What is sensitive data within the meaning of Art. 9? What is used for the performance of a contract according to Art. 6 para. 1 lit. b GDPR? What role does Art. 21 play?

This is almost ironic: with its questions for referral, the Cartel Senate of the Düsseldorf Higher Regional Court is now doing hard-core data protection law. In other words, Judge Poling-Fleuß who is the rapporteur is now engaging in a field that according to their indications the FCO should not be allowed to do. Depending on how this turns out the data protection activists may then go after Facebook on the basis of established ECJ case law (if it finds violations of the GDPR), thanks to the Düsseldorf competition court.

Twists and turns: The Cartel Office gets going because the Irish data protection authority remains inactive. The Düsseldorf Higher Regional Court has doubts as to whether the Cartel Office is allowed to apply data protection law at all. Instead, it does it itself and triggers a top court interpretation of the GDPR. If Facebook’s representatives were pleased today that the Düsseldorf Higher Regional Court has once again quite clearly lashed out at the Office, they will probably not be very happy about this reading.

The good news for the FCO

It was not an easy day for the team of the Cartel Office. Jörg Nothdurft said that, after the Senate’s presentation, he had expected the Office’s order to be held invalid today. Who could blame him? In the meantime, when Kühnen repeatedly said: “Clarification is needed…”, one may have thought of a referral according to Art. 267 TFEU. But actually, there was not much left to say in favour of the Cartel Office. And in particular, the court did not seek a legal discussion with the parties on the point of what to take to Luxembourg.

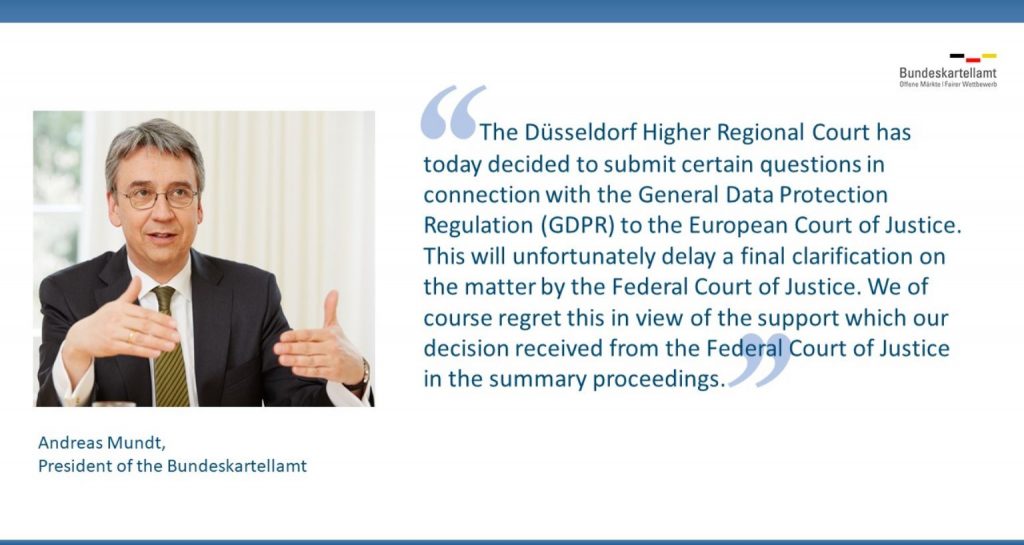

At least Kühnen let it be known that a representative of the FCO himself had “suggested” to him by telephone that the matter be referred (I tend to wonder what people talk about over the phone). The Cartel Office had also suggested this during interim proceedings at the BGH. But for long stretches of the 90-minute Kühnen lecture, nothing was actually heard of a referral. Against this background, the fact that the ECJ has come into play is news that should make the Office rejoice.

A referral under Art. 267 TFEU is only possible on questions that are relevant to the legal dispute. This means that whether or not the Cartel Office is proven right now depends on the answers from Luxembourg. Voilà! The Düsseldorf OLG apparently does not consider the way in which the Bundeskartellamt gives its reasons to be so misguided that the GDPR questions are irrelevant. Otherwise, there would be no need to consult the ECJ. Even in the assessment of Facebook’s handling of data, a critical approach to these questions became visible again and again – by no means was this an acquittal of Facebook. The “Register” button does not constitute effective consent. Nor do other measures. Some of Facebook’s explanations for users are “hardly readable”.

It is hard to imagine that the ECJ will affirm violations of the GDPR and that the Higher Regional Court will subsequently say: “Oh, we had only asked just for fun. This is not relevant for our case. Thank you anyway!” This is all the more true because in the almost exemplary examination structure that Kühnen went through (students, pay attention for structure!), there were a lot of subjunctives, auxiliary considerations, ifs and buts. No doubt: the trio on the bench thought the case through very carefully and then did not overturn it, but sent it to Luxembourg.

The good news for Andreas Mundt is that the Cartel Office can still win this legal dispute in Düsseldorf, and whether it does so now depends largely on the ECJ.

No good news for the BGH

However, until the announcement of the decision, this looked completely different. After the explanations on the GDPR, a thunderstorm came down, moderate in tone but powerful in substance. The office did not make any distinctions, did not give enough reasons, that is interventionist administration. And, holy moly, the BGH! Replaces the Office’s reasoning with a substantially different one, thereby changing the essence of the order. Probably inadmissible! The new line of reasoning (“imposed extension of benefits”) has no basis in doctrine (vulgo: off limits)! It also does not support the order as written down by the FCO! Facebook could simply stop its services, see Australia! There is no evidence that the users don’t want all that! The press release of the Higher Regional Court, which we found in our inbox as soon as we had left the mighty main portal of the courthouse, looking onto the Rhine, also deals with the errors of the Federal Supreme Court in much more detail than with the referral to Luxembourg.

On the value of science

On the question of whether it was an imposed extension of services at all, which apparently depends on what the users want, advocate Esser was happy to second. He obviously attaches great value to science, which the author of these lines is pleased to hear due to his profession. Esser was able to cite three expert opinions (which, as is customary in the industry, were probably not prepared pro bono by the authors). The “luminary” Professor Matthias Sutter from the Bonn Max Planck had come to a “devastating conclusion” regarding the survey of the Cartel Office, according to which more than 40 percent of the respondents said they could imagine switching to another network if it collected less data. In return, Nothdurft did not miss the opportunity to read out the core question from the consumer survey for the audience to judge themselves whether that was misleading… Oh, that was sweet.

Professor Martin Nettesheim from Tübingen has certified that the Cartel Office decision is contrary to European law. His colleague from Tübingen, Stefan Thomas, has written on causality – this expert opinion is, however, likely to be of historical value after the amendment of Section 19 of the GWB, which is of relevance here.

As far as the value of science is concerned, however, there are distinctions to be drawn: Commissioned expert opinions are of a high value, but 10-year-old doctoral theses are not. Roland Broemel, a learned colleague from the University of Frankfurt, had been cited by the BGH with his PhD book “Strategisches Verhalten in der Regulierung” published in 2010. Kühnen stated that the BGH had misquoted Broemel. Esser, later: What is the relevance of a 10-year-old PhD-thesis… adding that the Presiding Judge had said everything about that (who, however, had said he would not say anything on relevance). (I would have liked to know whether Esser’s verdict of irrelevance-theory also applies to this work. Unfortunately, it was not clarified. But this man has a sense of humour, I know that, he would certainly have had a good line to say about it!) (By the way: A list of not-so-old dissertations on antitrust law can be found here!)

What data exactly?

Two points still hit the Cartel Office to the core.

No. 1: There is not enough differentiation between different data and their effects. It is obvious that Facebook is allowed to collect certain data – the office has to be more precise.

At points like this, it was noticeable again and again that it would no longer be possible to reach an agreement between the Office and the Senate. They read the FCO decision differently. The Office, as Nothdurft put it, is concerned with a power problem – and the accusation here is not that individual data was collected unjustly, but that Facebook imposes its conditions on its users without leaving them a choice, thereby amassing its power. Nothdurft countered the accusation of too little evidence on exact data and justification with an interesting metaphor and an interesting statement. The metaphor: Facebook has just “taken a big gulp from the bottle”, they collect everything they can somehow get, that’s what it should mean. There had been no discussion with Facebook about what was necessary, because Facebook had declared everything to be necessary.

And now the interesting thought: The differentiation of what Facebook has to do in detail is part of the remedial measures. That’s why Facebook was first asked for an implementation plan in order to see exactly what would be sufficient.

The concept of an undertaking in cartel law

No. 2: The already mentioned “et al.“. The Bundeskartellamt has addressed the injunction to Facebook Inc. (USA), to the Irish Facebook branch that does the data processing, to Facebook Germany and to all affiliated companies of these companies. Here Kühnen left no doubt: this is illegal. He switched from the otherwise frequently used subjunctive to the indicative. The data processing is handled by Facebook Ireland, the others, certainly not any subsidiaries, sister companies or second-tier subsidiaries had anything to do with this case, they had not even been heard, there was no discretionary consideration of this addressee position. This had something of a game over. An illegally addressed order!

Nothdurft to the rescue! And I may now allow myself a few lines of fanboy here: the way Jörg Nothdurft responds to such considerable reproaches in a powerful, concise, comprehensible and free speech manner – that is truly great art. In the Kühnen/Nothdurft dialogue, competition law becomes Netflix-material. After the lunch break, Kühnen opened the rest of the hearing by saying that what the Federal Cartel Office had said before lunch needed a response from the bench. I guess you could call that a pat on the back.

So what did Nothdurft say in response to the allegation that the addressing of the injunction was unlawful? The following: The “operating company” had been addressed, and that was what was at stake. We are dealing with a whole “cosmos” – one of the most powerful and strongest companies in the world. And this is not about factories and conveyor belts, but about digital services that can easily be moved from here to there. Facebook would only have to change its imprint, then the FCO order would already run into the void. “If that is the case, we can no longer investigate such companies.” One wonders about the concept of an undertaking under competition law – but my colleague Christian Kersting is responsible for such questions in Düsseldorf.

Towards the end

Sebastian Louven for the consumer association also had his say. He reminded the audience that this was not so much about the GDPR (“I thought we had that out of the way”, he said, alluding to the BGH take of the case), but about a violation of antitrust law. He also reminded the audience of the fundamental rights aspects (his luminary: Prof. Oliver Lepsius). And he spoke of consumer sovereignty – the protection of the consumer as a core concern of competition law. Towards the end, these were once again the three bullet points that were good to hear for all those who seemed very sympathetic to the solution provided for by the BGH, but wiped off the table by the OLG (I am one of these people, see my paper in GRUR 2020, 1268 ff.).

What happened next: pause. Counselling. A mini-pizza and a Coke in a hurry, consumed 50 metres away from the pizzeria, as is Corona law in Germany. We didn’t need the Coke. At the reopening, it was now 3 p.m., Judge Kühnen told a rather surprised audience: “We are suspending and referring to the ECJ on questions of the GDPR.” The decision would be handed down in the next few weeks and the court would wait for the answer. And that was it. Nearly.

When will it be enforced?

“Now, we are just performing secretarial duties”, Kühnen said almost coquettishly. A burden fell from him, too, it seemed, after this exhausting hearing. The question of the day remained open: Does the FCO actually enforce its injunction now? After the BGH ruling, there is no suspensive effect for Facebook at present. And, how timely, the deadline for the first implementation step expires next Monday. Then Facebook must submit the famous “implementation plan”. The Cartel Office is allowed to demand this. But will it do so – despite the risk of liability in case they are proved wrong in a couple of years?

The Facebook representatives gave the impression that it was an undue hardship to have to present an implementation plan in three days (!), as if they had only just been informed. One would like to know how far the work on such a plan has progressed. Or were they relying on the OLG to bail them out in time?

Nothdurft felt unable to make an ad hoc decision. He wanted to call the office first (just like a trainee public prosecutor has to do in Germany). The decision is with the decision division (headed by Julia Topel), not with him. During lunch break, he had obviously prepared himself for the situation that the OLG would side with Facebook today. That was what it had looked like. To enforce with a lost court case in the first instance court, that would be a brave move. But now? With the ECJ as a potential game changer?

Esser announced: If the FCO wishes to enforce, Facebook will file a new application for an order of suspensive effect. Kühnen would be responsible for this again, and he promised to decide quickly – if necessary within days. I would hope that the implementation plan would at least be called in. The risk of liability for this first step would be quite manageable… But academics dream such dreams.

One jump, one sentence

So what remains after this day?

The waiting time until the ECJ decision is 15.5 months on average, I gathered from Simon Van Dorpe’s Twitter account. If the Grand Chamber decides and Corona delays play into it, it will probably take even longer, Anton Dinev added. So we are deep into 2022, when the OLG will have to decide again. Then, in all likelihood, it will go to the BGH again. If that is the end of the matter and there is no further appeal to the ECJ or the OLG, we will probably be in 2023 at least – if not later. By then, we may already have the Digital Markets Act and a Section 19a GWB case against Facebook. What is at issue here is explicitly regulated there – in Section 19a (2) No. 4a GWB in the version that has been in force since January 2021, and in Article 5a of the DMA proposal.

Regardless of whether you think the FCO case is right or wrong – all this takes too long. The Bundeskartellamt has been on this case since 2016. Five years and several court decisions later, we have not made a single step forward in the result, neither in one direction nor in the other. It seems to me that our beloved field of law is choking on substantive and procedural complexity. This is not an accusation against the parties, who only show “strategic behaviour in regulation”, as Broemel called it too many years ago, nor against the courts, which have to examine what they have to examine. If, however, there were still a need for proof as to why speeding up-regulations such as Section 19a of the German competition act or the DMA are necessary, then let everyone turn their gaze to this case and ask themselves whether effort and return for the markets are still in proportion.

As far as content is concerned, Jörg Nothdurft deserves the last word: “Either you jump or you don’t jump. That’s how it is in the digital economy.”

Even if it didn’t look like it at first: The Senate has jumped.

Rupprecht Podszun is a Director of the Institute for Competition Law at Heinrich Heine University and the editor of this blog. He thanks Philipp Offergeld for important advice. You can find a lot of information on the Facebook proceedings here: https://www.d-kart.de/en/der-fall-facebook/. After publication, the wording of one sentence and some typos were corrected #netiquette.

The Facebook case will also be this week’s topic in our (German language) podcast with Justus Haucap and Rupprecht Podszun – “Bei Anruf Wettbewerb”. Available wherever you hear good podcasts!

10 thoughts on “Facebook: Next stop Europe”

Liebes D’Kart-Blogteam: Gratulation zu der raschen und genauen Beschreibung des gestrigen Termins, den ich genauso erlebt habe: ein beeindruckender 90 Minuten-Vortrag von Prof. Kühnen, ein fulminanter Push-Back von Dr. Nothdurft und ein smarter Schachzug des OLG als Abschluss. Die Frage ist, ob der EuGH – so wie der BGH auch – den Facebook-Fall umfassender einordnen wird?

Doris Hildebrand, EE&MC/Paris Sorbonne & Nanterre

Ich frage mich mittlerweile, ob das Land irgendwann die Reißleine zieht und die Kartellrechtszuständigkeit nach Köln gibt.

Suppose Section 19 of the GWB actually is stricter than Article 102 TFEU, and that the FCO was correct not to apply Article 102 TFEU (as they otherwise should have done according to Article 3 of Regulation 1/2003). Should the ECJ in that case reject the request for a preliminary ruling because it is not relevant to the legal dispute?

very interesting, thanks (why not a printable version?)

Sehr interessanter Auftrag zum Thema Wirtschaftsrecht / Kartellrecht!

Really a great post.