SSNIPpets (47): Voilà – le DMA!

Finally. The Digital Markets Act #DMA is here! Rupprecht Podszun has not yet seen the little sister of EU antitrust law, but he has seen the rather proud parents at the press conference. Plus, he has comments on the war in Ukraine and courts doing their job well or not so well. Here are his SSNIPpets – small but significant news, information and pleasantries – our pet project!

On the war

In other times, this would have been big news: The Digital Markets Act is coming.

But times are not as they usually are, unfortunately. The DMA finds its echo somewhere hidden in the business section of the newspapers. Other news is more important – and more shocking. When I look at the war through the glasses of a competition lawyer, I am moved by a great disappointment: Free trade, secured by competition rules, agreements and WTO frameworks, has always been an insurance of peace for me. Those who are closely intertwined economically do not shoot each other. Perhaps I was naive.

On the other hand, if Russia’s conglomerates had been less highly concentrated, if there had been stronger antitrust enforcement, if the political sphere had been governed by free and fair exchanges, this war would probably not have happened. Perhaps I don’t have to give up completely on the hope that economic and democratic competition can bring about peace.

One bright spot is the commitment to Ukraine. When my colleague (and podcast partner) Justus Haucap recently asked some lawyers if anyone could take on a Ukrainian antitrust lawyer who had fled, he quickly had several offers.

Dependencies

The German reaction to the invasion is determined by an energy policy that has become entangled in unbearable dependencies over the years. Dependence is something we know very well in competition law. So, we have some tools to analyse the situation.

From a competitive perspective, the German reaction is made worse by the fact that gasoline prices in Germany serve as fuel for populists. Goodbye, Ordoliberalism! Of course, this is only one of the minor collateral damages that we have to accept.

Another topic that is interesting due to increased spending in the sector is competition on defense markets – a topic I haven’t looked into ever since 1989 when the German defense merger of Daimler/MBB gained ministerial approval after having been blocked by the Bundeskartellamt. Well, at that time I didn’t even know what merger control was.

Incidentally, in the recent Miba/Zollern case, where the Minister of Economics granted another of his political approvals overriding the competition agency, arms policy arguments were again put forward as a public welfare reason. However, then-Minister Peter Altmaier preferred to rely on the soft green arguments to justify the ministerial permit. Plain bearings for wind turbines instead of plain bearings for tank engines.

More info on War & Antitrust:

The ECN intends to treat cooperation agreements that become necessary, for example, because of supply chain disruption, according to the Covid framework.

ICN Chairman Andreas Mundt has suspended the Russian antitrust authority from participation in the International Competition Network.

Wirtschaftswoche writes about what has become of the OPEC oil cartel; Justus Haucap told me what there is to say about gasoline prices in a special episode of our podcast “Bei Anruf Wettbewerb” (in German).

Eugen Wingerter, a Düsseldorf lawyer and a professor in Dortmund with Russian roots, gave me a moving interview for the German competition law journal WuW.

Is market power per se a problem?

Germany’s dependence on Russian gas is a bitter reminder of how destructive dependence can be. For years, however, it was hammered into our heads that market power per se isnot problematic, but only the abuse of market power. I never really understood that. Every economics textbook names monopoly or quasi-monopoly structures as causes for market failure. So it surely must be bad! But I didn’t really dare to question the mantra ever since I had a journalist at the Fordham Conference 2009 in the U.S. shove the Microsoft decisionofthe European Court under my nose (literally!), combined with the question:

“So do the Europeans say that market power as such is illegal???”

The evidence for this, from the point of view of the questioner, abstruse opinion was a misleading paragraph in the CFI decision (which I unfortunately can’t find now). At that time I surely murmured something like: No, no, market power is not bad as such.

Today I would answer more accurately: The abuse of market power is prohibited by law. This does not mean that market power as such is unproblematic, especially if it takes the form of a monopoly. This, in turn, does not mean that every monopoly must be broken up and all market power must be prevented. But the mantra, such are mantras, has obscured our view of the fact that for a market economy to function, it is not enough merely to prove abuses. Which, as we all know, is difficult enough.

Perhaps dependence is a better term than market power. It expresses more clearly that protecting competition is about freedom. A freedom that Germany now lacks in its political response to the Russian war of aggression.

DMA – proud parents

This has been a bit of a long run-up to the DMA. The Digital Markets Act regulates companies, most of which have been able to grow pretty much undisturbed by legal rules for over 20 years. This kick-start for Google & Co. is now coming to an end. That’s right, because countless companies and consumers have long since become dependent on digital ecosystems. This is not always associated with an abuse of market power, but often with a loss of freedom. (People who don’t feel this way, or even welcome it, are those who reach for convenience food in the supermarket and say, “Hey, that looks healthy!”)

The trilogue negotiations reached a breakthrough shortly before midnight on March 24, 2022, with a “political agreement” on a text. The text now needs some final polishing, it will be officially confirmed and then published in the Official Journal. Six months later, it is applicable. Companies then have three months to notify their gatekeeper status, and the Commission in turn has a maximum of 60 days to classify the company as a gatekeeper. In short, if everything goes smoothly, we will see the first effects of the DMA in spring 2023. But when does everything ever go smoothly?

The EU will enter a new phase: the era of regulating digital gatekeepers will begin, and to some extent the era of antitrust law will end.

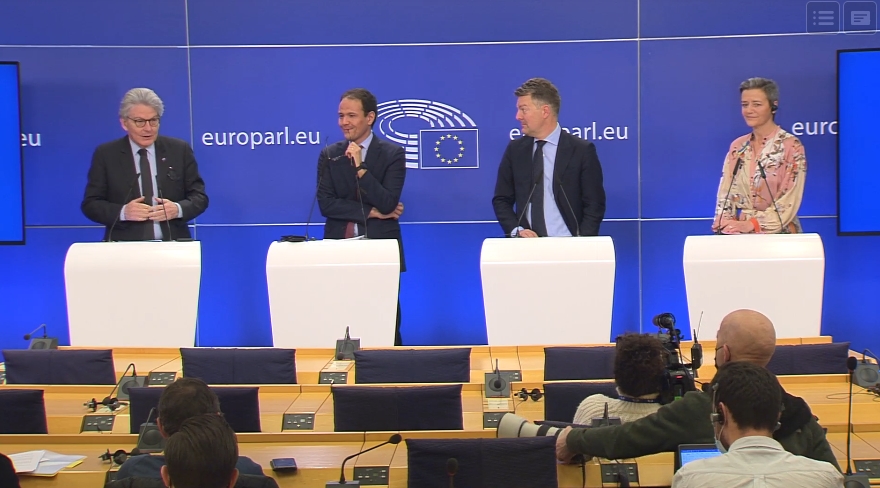

At the press conference, the DMA was presented by four co-parents: Andreas Schwab for the European Parliament, which acted with persistence, many proposals and Schwab’s expertise; Margrethe Vestager and Thierry Breton for the Commission; Cédric O, the French “Secrétaire d’Etat chargé de la Transition numérique et des Communications électroniques” for the European Council. Breton gave marks to his fellow campaigners, all of them got a straight A. Vice-President Vestager, for example, formally his superior, had to accept Breton’s approval as the world’s best in antitrust; he seems to know a lot about it. Breton himself (who had published a Spotify playlist on the DMA in advance) gave himself a straight A, too, I think. At least, he pointed out that he had already written a book on the subject at the age of 28 or 30 (age varying). He probably meant Softwar – La Guerre douce, a book that became a bestseller in 1984.

Inspired by the United States

The French in particular had been pressing, and so O said at the presentation (in French, of course):

“L’Europe, elle, est parfois caricaturée pour sa lenteur, pour sa bureaucratie.”

But the fact that the text was adopted so quickly shows that the EU is up to date. Hm, hm. So Europe is managing to hammer out new regulations in a reasonably short period of time (this benchmark is also likely to be reviewed). It is less able to give birth to successful digital champions. Eh bon… (I was similarly irritated recently by the words with which the German government celebrated the new Tesla factory built in Germany as a symbol of speed; after all, Tesla’s Elon Musk had built the plant at its own risk without the official permits).

EU politicians have resisted US lobbying attempts. What the GAFA groups have spent in lobbying money in Brussels, and that was not exactly little, seems to have been spent in vain. However, we are trained to think about the counterfactual: Perhaps the rules on merger control, breakup, targeted advertising or data combination would have been much tougher without U.S. pressure from business and politics? The Biden administration had a certain credibility problem: Here Gina Raimondo, Secretary of Commerce, who consistently railed against the DMA. On the other hand, FTC chief Lina Khan, presidential adviser Tim Wu & Co. who themselves promised to tame Big Tech. To a September 2021 meeting of various agencies, Wu wrote they wanted to

“boldly go where no antitrust agency has gone before”.

The sentence is well put, like so much of Tim Wu, but – as one of my PhD students with special skills tells me: this is a reference to Star Trek. Well, with the DMA, we are indeed entering unknown galaxies that even the German Federal Cartel Office has so far only seen from afar in its pioneering voyages.

It is unclear how far the antitrust authorities can still go. Even if the anti-GAFA-provision in Section 19a of the German act against restraints of competition remains applicable, as a press release from the Federal Cartel Office indicates (and anything else would have been a mockery!), there will in fact be a certain shift of importance in the direction of Brussels: Starfleet’s command center is in the Commission now. I’m curious to see how coordination, administrative assistance and balancing will work out, and whether the Bundeskartellamt will really withdraw from the digital scene for the time being. I can’t and don’t want to imagine that.

But whether enforcement really works in Brussels is another matter, about which we know even less than about the paper on which the DMA is printed. (A shout-out to consumer advocate Miika Blinn, who elicited a laugh from me with a tweet about his tattered printed copy of the DMA draft – I’ve grown fond of the thing, too!) Vice President Vestager responded to a question by Politico’s Sam Stolton about how the Commission now envisions the internal organization of enforcement, that this “may be of second order interest”. Madam Vice President, you underestimate our geekiness!

Even more US references

Cédric O invoked the legendary saint of Progressive Antitrust, Louis Brandeis, and called the DMA an echo of the Sherman Act – precisely in its combination of economic and democratic aspirations. Tom Wheeler, former head of the U.S. Federal Communications Commission, provided O with the slogan of the day:

“Don’t break them up, break them open.”

(Whereby breaking up is probably not yet completely off the table in the DMA either).

I will leave the DMA topic now until we have a reliable text – there is already enough speculation, and the statements at the press conference, for example on merger control, were too vague for our specialist community.

Final observation: Council representative O noted that the trilogue final was the first time he had seen people from “inside the room” tweeting in ongoing negotiations. He seemed to find that somewhat disconcerting. The man is definitely not suitable for German party committees.

Next big thing: Data Act

The next big thing in the digital regulation puzzle is the Digital Services Act, followed by the EU Data Act, a draft of which has been submitted by the European Commission. I am sure that it will be more difficult to reach an agreement. European economic interests are essentially affected here. As a representative of an association recently put it in an online discussion, the question is whether the European industry will now have to give away its silverware. That was an exaggeration, of course, but there is some truth to it: the silverware of the future is seen as the data generated by product use, which opens up a huge field for associated services and secondary markets. The silverware image doesn’t fit, however, because with silverware, ownership is usually relatively clear: “Originally, my great-aunt Adelgunde (A) was the owner of the silverware. She gave it to uncle Gotthold (G). He in turn bequeathed it …”

In the case of data generated by the use of a product, there is no legal attribution. They belong neither originally nor later to anyone, and it is by no means a matter of course that the manufacturer of the product must automatically also be the owner of the fruits of the use of the product. In the material world, we would find it rather astonishing if the garden center that sold the apple tree were to say: The apples, of course, belong to us.

Move the dial

The antitrust community is feverishly awaiting the first major in-person events, as far as they are not currently positively tested – or just then. One such event is undoubtedly the Brussels conference organized by Cristina Caffarra and CRA on March 31, 2022. With so many big names on the podium (from A for Khan to M for Mundt to Z for Coscelli), it was easy to smuggle my no-name. For 30 minutes, I am allowed to serve as a punching ball sparring partner for Marc van der Woude, the president of the EU General Court. We will discuss whether European courts are standing in the way of a more progressive application of competition rules. Or, in Caffarra’s words, “Will the courts help move the dial?”

One of the questions intriguing me is: to what extent are courts relevant at all? Many cases no longer even reach the stage of judicial review. Three examples from the automotive industry:

- The highly controversial “Emissions Cartel,” in which restrictions on innovation were the cause of a large fine, remained untested.

- Although the trucks cartel has triggered many follow-on proceedings for damages, only Scania has challenged the Commission’s decision in court, unsuccessfully in first instance as we now know.

- For the third example: Later.

As a result, the courts can no longer comment on landmark cases and exciting legal issues, whether because companies don’t want to go through a years-long odyssey through the judicial system or because it’s easier for authorities and affected parties to agree on settlements or commitments. Who can blame them? Still, it’s a pity. And something to worry about.

Decision of the week

Nevertheless, there still are fascinating cases, not least in private enforcement. My recommendation for the week: The decision of the Kammergericht, the Berlin Higher Regional Court, on Section 20 (3a) of the German competition act. This anti-tipping paragraph, introduced in 2021, states:

“An unfair impediment (…) shall also be deemed to exist where an undertaking with superior market power on a market within the meaning of Section 18(3a) impedes the independent attainment of network effects by competitors and in this way creates a serious risk of significantly restricting competition on the merits.”

Yes, friends, it says competition on the merits (Leistungswettbewerb), I know that’s spectacular, but that’s not my point. Above all, the provision opens up a far-reaching possibility for intervention. The Berlin Court, just like the first instance court, ruled on a first case of application by way of a special order in interim proceedings. The case involves a dispute between two real estate portals. One, the market leader, offers brokers discounts if they place 95% of their listings on the market leader’s websites (“list-all rebate”) or if they place their listings exclusively on the market leader’s websites for the first seven days (“list-first rebate”).

The decision is worth reading for several reasons (if you know German, that is). First, it shows what antitrust law can do in the digital world, without DMA. Second, it is so clearly reasoned that it is a pleasure to read. A rapporteur has really taken the trouble to go through and carefully fan out digital competition law. If you need a crash course on network effects or tipping markets, this is the place to be. When you have struggled with a meandering ECJ decision, where in the end you no longer know what it was all about, you quickly appreciate the clarity of some decisions. Thirdly, as a scholar, I am pleased that two colleagues, Heike Schweitzer and Thomas Ackermann, have provided expert opinions for the parties on the application of the new standard that are looked at by the court.

When applying Section 20 (3a), the crux is in the question whether the far-reaching rule needs some limitation. Aren’t type I-errors programmed here? The Kammergericht writes:

“Knowing the difficulty for courts and authority to identify those situations in which a so-called tipping is likely without intervention (…), the legislator has opted for an extension of the prohibition of abuse at a relatively early stage for preventing the risks for competition and it has consciously accepted the associated risk of overenforcement.”

In other words, the 10th amendment of the German competition act #GWB10 was intended to enable more intense intervention in markets. If the legislator says so, then, as a court, you have to jump. I will perhaps remind Marc van der Woude as a precaution in case his court has to decide on the DMA one day.

No judgment is a good judgment

At the German Federal Court of Justice (Bundesgerichtshof) there is still no new chairman (m/f/d) for the Cartel Senate, although Peter Meier-Beck retired in September 2021 (which was foreseeable). Months ago I had inquired with the press office, how it stands. Answer: “At present it is not yet foreseeable…”. Whether this is still true? First, the Federal Ministry of Justice has to appoint someone as presiding judge, then the presidium of the Court decides who gets which senate to lead. For the time being, professor Wolfgang Kirchhoff, well known in the antitrust community, is in charge of affairs.

Meier-Beck – freed now from the shackles of office – gave an interview to German law gazette JUVE. My favorite part relates to the question of whether he would have liked to see an ECJ decision in the Connected Cars case Nokia/Daimler (voilà: car example No. 3). The two companies were fighting over patent licenses and FRAND. The Düsseldorf court submitted essential questions to the Court of Justice in Luxembourg in this regard (Case No. 4c O 17/19). But: Nokia and Daimler settled, there will be no preliminary reference on this. Ex-Judge Meier-Beck does not mourn the missed opportunity for an ECJ decision:

“Some answer would have been given by the judges, of course. But probably, it would have been very vague, and then all the experts would have stopped thinking about an appropriate solution to the current problem. Instead, as we saw with the 2015 ECJ ruling in the Huawei/ZTE case, they would have rushed to interpret the more or less cryptic new ECJ ruling.”

Well said! Somehow encouraging that a retired judge recognizes the limitations of the judiciary.

A good start into a new week, which hopefully may bring better news than the last weeks!

Rupprecht Podszun is the Director of the Institute for Competition Law at Heinrich Heine University in Düsseldorf. This week he serves as a Global Law Professor at KU Leuven.

Stay tuned: You can subscribe to our e-mail newsletter here (please check your spam folder and confirm your subscription!)

We corrected the date of the agreement – a reader alerted us that the breakthrough was before midnight – see the blog of Simonetta Vezzoso.

4 thoughts on “SSNIPpets (47): Voilà – le DMA!”

I have a question about the decision of Berlin Higher Regional Court on Art 20 GWB. I wonder why the court refused to disclose the name of the claimant and respondent. Is there any relevant legal basis to justify the concealment?

Good question! That is standard practice by German courts, but it is not mandated by a specific law. In this case, it is known that the parties are Immoscout and Immowelt, see

https://www.juve.de/verfahren/kampf-der-immobilienportale-erstes-tipping-urteil-ist-rechtskraeftig/.

Thank you for your answer. In my opinion, for the sake of transparency and given the increasing role of interim orders in the context of digital market, the courts should disclose the name of the parties.

Eine weitere Gemeinsamkeit zwischen dem Kartellrecht und dem Angriffskrieg Russlands ist die Spieltheorie.

Johann von Neumann, der Begründer der Spieltheorie, hat lange Zeit bei der RAND Corporation in den USA geforscht und sich dort unter anderem mit der nuklearen Abschreckung befasst. Die RAND Corporation ist im Grunde der „Geburtsort“ der Spieltheorie (auch John Nash und Kenneth Arrow forschten dort). Die Theorie militärischer Abschreckung basiert im wesentlichen auf einem Beitrag von Herman Kahn aus dem Jahr 1960 mit dem Titel The Nature and Feasibility of War and Deterrence, der auch heute noch aktuell ist. Sowohl von Neumann als auch Kahn waren die Vorbilder für Dr. Strangelove im gleichnamigen Film des Regisseurs Stanley Kubrick (1964). Auch Thomas Schelling, der Kartellrechtlern vor allem wegen des Begriffs „fokaler Punkt“ (auch Schelling-Punkt) bekannt ist, war lange Zeit bei RAND tätig und hat gleich zwei wichtige Beiträge zur Abschreckung bzw. der Anwendung der Spieltheorie auf militärische Konflikte geliefert: The Strategy of Conflict (1960) und Arms and Influence (1966) geliefert.