Antitrust Super Tuesday

PDF version: Click here

Suggested Citation: Podszun, DKartJ 2023, 54

Such a mass of competition law developments on a single day is rare: Germany is getting the “New Competition Tool”, i.e. an amendment to its competition act, the ECJ has ruled in the matter of the Federal Cartel Office vs Facebook, and the companies that see themselves as digital gatekeepers in the sense of the Digital Markets Act have reported to the European Commission. Whew. On the Fourth of July 2023, an antitrust festival virtually took place in Europe. Rupprecht Podszun sifted through the events of the day.

Little Tuesday

Little Tuesday is a detective, he is one of Emil’s gang, that wonderful investigator character dreamed up by Erich Kästner. Emil Tischbein had 140 marks stolen on his way to Berlin by a crook called Grundeis. With the help of a special investigative commission – Gustav mit der Hupe and Pony Hütchen – Emil chased the perpetrator, caught him and could rely on Tuesday, who was on telephone duty (“Parole Emil”). Emil and the detectives had qua imagination unlimited resources and investigation possibilities. The dawn raid ended in a bank, Grundeis’s illegal profits were skimmed off, he was taken into custody and Emil was invited to eat cake by a journalist called Kästner. Well, that is a well-known German child book with this guy called Little Tuesday.

The 4th of July 2023 was not a little Tuesday in Europe, but a big one, an Antitrust Super Tuesday in fact, with all my favourite topics: Meta and ministerial permission, a burst knot and dashed hopes.

The biggest reform since Ludwig Erhard

Let’s start with “tamed hunting dogs”, i.e. the Bundeskartellamt, and let’s fast-forward two days: At 6:16 p.m. in the early evening of 6 July in the year 2023 of our calendar, the German Parliament Bundestag convened and agreed in 2nd and 3rd reading to a “paradigm shift” in competition law and passed a reform of the Act against Restraints of Competition (GWB) – and indeed “the biggest since Ludwig Erhard” (State Secretary Sven Giegold from the Federal Ministry of Economics (BMWK) on Twitter). The knot was, so it was said, broken on Monday night: the government parties agreed on the final wording of the law. It was sent to the Members of Parliament on Tuesday, i.e. 48 hours, not 14 days before the vote.

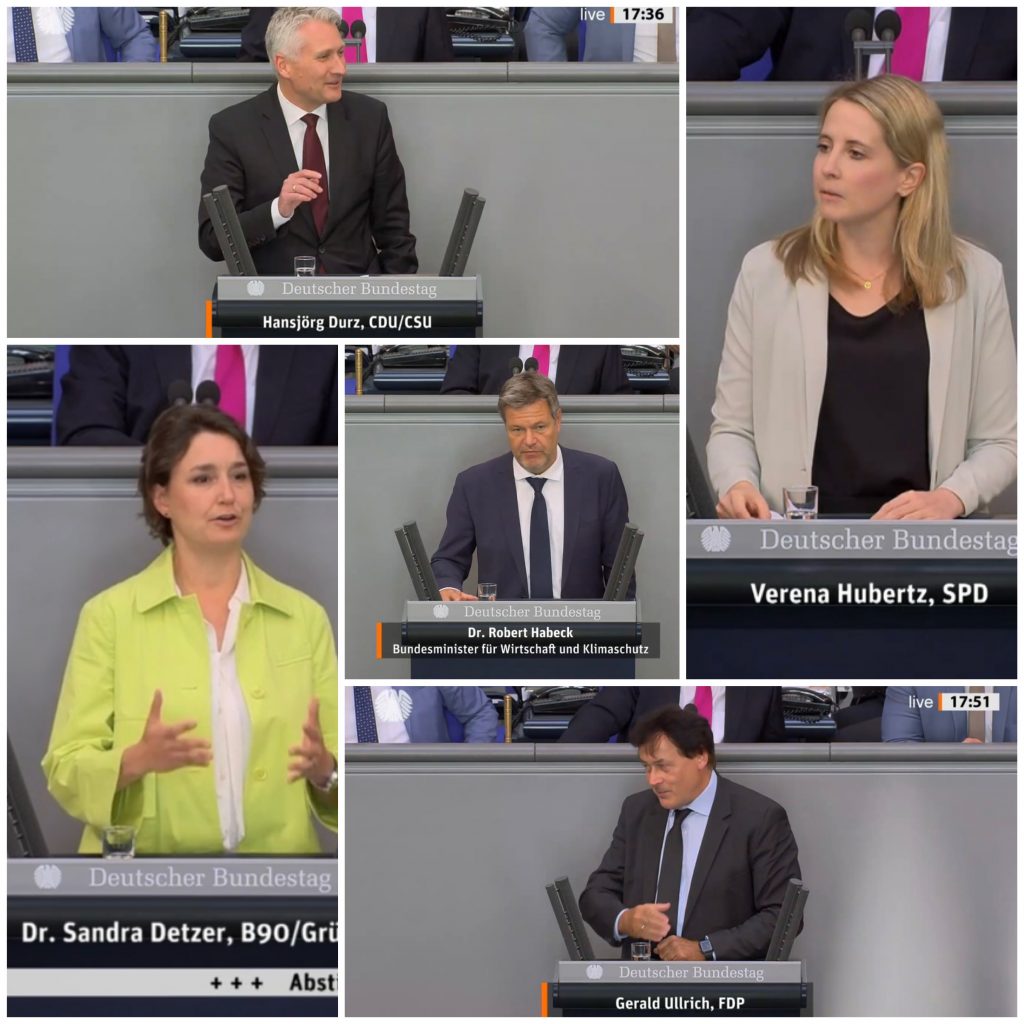

The Federal Constitutional Court did not stop this rather short-term consultation, as it had done just a day before with another German law for lack of time for Parliament to go through the text. But in the case of the GWB there was no plaintiff, with no plaintiff, there is no constitutional veto. Opposition politician Hansjörg Durz (CDU/CSU) confined himself to a few enjoyable points (his speeches on competition policy are on point anyway, even if one disagrees on the matter):

“You say you are presenting here the biggest reform since Ludwig Erhard, but you hide it as if it were unpleasant for you. (…) Fundamental changes need broad political debate in a democracy.”

And good laws also take time. I am writing this in the knowledge that I myself had a learning curve with this GWB amendment – even a law professor (well, certainly not me) doesn’t always notice the issues that could still be changed when reading a draft for the first time between teaching civil procedure and the faculty council meeting. More about my learning curve later.

Bumper Sticker Material

Let’s get this straight right away: I’m in favour. In the meantime, this amendment to GWB has taken on a polarising character. You just have to take a stand. In the USA, we would already have bumper stickers: “When competition is disturbed – leave an emergency lane!” or “GWB11 – I stop for cartel enforcement”. I found some of the statements in the debate a bit shrill in their choice of words. But maybe that’s the way it is, the attention economy of the lobbyists. Perhaps some associations still have to get used to the fact that cargo bikes are currently on the fast lane to the green decision-makers in the Economics Ministry.

There are three topics in the GWB amendment that Florian Wagner-von Papp has already described here: the enforcement of the DMA in Germany, the facilitated disgorgement of profits from competition law infringements (Section 34 GWB) and the power for the Federal Cartel Office to take measures following sector inquiries even without a violation of the law, namely in the case of a significant and continuing disturbance of competition – up to and including unbundling (Section 32f GWB). This was once discussed at EU level as the “New Competition Tool”. For more details on the latest status, please refer to the small print in this overview.

The Big Points of the Novel

I was always puzzled by the fact that the focus was on Section 32f GWB, and there on issues whose practical relevance will possibly remain manageable. If I had to guess what we will see above all, it would be two points that hardly played a role in public discussions: First, the thresholds for stricter merger control following sector inquiries in Section 32f(2) GWB are considerably lowered compared to the previous Section 39a GWB. Instead of 500 million (acquirer) and 2 million (target) EUR turnover, only 50 million and 1 million EUR turnover will be required in future. My guess: As a result of sector inquiries, there will first be a considerable expansion of merger control for certain companies in the future, especially since this can be enforced more easily than everything else provided for in Section 32f GWB.

The other big point of the amendment is the facilitated disgorgement of profits according to Section 34 GWB. (This has nothing to do with the market investigation tool, but is a general provision). A profit of 1% can be skimmed off quite easily with the help of an almost irrefutable presumption after an infringement of competition laws. MP Sandra Detzer (Greens) thankfully pointed out in the concluding Parliament debate that an essential requirement of the rule of law is thus realised – that the perpetrator is not left with the fruits of his crime. Emil Tischbein and Little Tuesday in the child book understand this without further ado. Yet, according to the Bundeskartellamt itself, the German practice up to now has been different: The fines allegedly do not skim off any unjust gain, but merely punish the unlawful act. The new provision could become an expensive game changer for competition law infringers, especially when abuse of dominance is at stake, where there are hardly ever financial sanctions in Germany (no fines, no damages, no disgorgement of benefits).

On the practical relevance of the new tool

The last amendments to Section 32f GWB lower the subsidiarity clause somewhat (i.e. the issue whether it first has to be established that the behaviour in question cannot be remedied with traditional competition law proceedings). Changing that subsidiarity clause is a reasonable step. Also, legal protection is strengthened by giving suspensive effect to appeals against measures taken by the Bundeskartellamt after sector inquiries. From the lectern, Sebastian Roloff (SPD), who had acted as Parliament’s rapporteur, expressly thanked the team of the Federal Ministry of Economics around Thorsten Käseberg, who must have invested some nerves into the wording of the Market Investigation Tool. So what has come out of it now? In the words of Verena Hubertz (SPD):

“The [Federal Cartel Office] is not a tiger that we let out of some cage, but it is a well-tamed hunting dog.”

Right after the vote in Parliament, Andreas Mundt, leader of that hunting pack, tried to lower expectations a little:

“With the application of the new provisions, we will be entering new territory, with many new legal questions. The procedure is very complex, offers the affected companies extensive legal protection and is subject to very high evidence requirements. Proceedings will probably take years.”

And of course, the ceterum censeo of a head of authority could not be missing:

“We hope to get the resources we need to do this.”

The bars of the tiger cage

Mundt is right. The “biggest reform” ever ever ever will play a limited role in practice. And that has also been a major point on my learning curve, after I had initially let myself be carried away by what a paradigm shift is in store when it is no longer an infringement of the law but “only” a disturbance of competition that becomes the starting point for executive intervention. The sector inquiry plus will probably be a rarity, but it will be really helpful in the cases then examined. So far, the Bundeskartellamt has only completed one sector inquiry per year, if at all. With increased requirements and the reduced willingness of companies to cooperate in sector inquiries (they must now expect that something will follow), the number will decrease rather than increase. There is really no question of a tiger out of control, snatching up companies at whim.

The second point of my learning curve (after I too had racked my brains as to how to define the disturbance of competition more precisely): The real limitation of an extensive interpretation of the necessarily open concept lies not in piling up new material terms (essential, substantial, special, continuous, terrible, worst ever), but in a procedural safeguard: through judicial legal protection, but also – this is my plea – through a broader set-up within the Bundeskartellamt. Decisions in the German competition agency are independently taken by chambers of three members (similar to courts). That looks a bit weak for decisions based on the Market Investigation Tools. Why not have another Decision Division cross-check with “a fresh pair of eyes”? Why not set up a larger decision senate, chaired by the vice-president, as Heike Schweitzer (HU Berlin) suggested? This would promote the uniform interpretation of the many new terms, and that is all the more important when there are not many opportunities to do so. In addition, this would be a further safeguard in case a decision-making trio turns wild (such cases of institutional capture are said to exist, although of course never at the Bundeskartellamt). The legislator has not provided for this safeguard; there would still be room for it in the Bundeskartellamt’s rules of procedure.

Is that even necessary?

The key question remains: Are there constellations or sectors in which antitrust law is currently not getting anywhere? I do believe that there are such situations of a structural lack of competition. My Mannheim colleagues Martin Peitz and Jens-Uwe Franck saw it the same way in the expert hearing. Even Heike Schweitzer, who is not suspected of being sympathetic to hipster antitrust, affirmed such a need for readjustment in the expert hearing. She would react to this with selective amendments to the ARC. I prefer the general clause of “distortion of competition”, so that we don’t have to make costly readjustments every time there is a new phenomenon in the market. If you look at the previous sector inquiries and their results (Tristan Rohner and I summarised this in a statement for the Bundestag, see here page 11f.) you get the impression: Yes, these could really be areas where a small competitive impulse would be helpful.

To sum up: In the future, the Bundeskartellamt can provide some stimulation in markets that fell asleep. Hurdles for the Amt are high, but still it is pretty amazing that it can interfere without an infringement of the law. This can be viewed critically because of the general clause-like wording. One could restrict the Bundeskartellamt more in terms of procedural safeguards. It can also be argued that in such cases the legislator should intervene (a counterfactual that friends of competition may view with mixed feelings).

The following criticism, however, seems rather exaggerated, to say the least:

“The planned changes will dampen competition and thus tend to lead to higher prices” (Stefan Genth, Managing Director of the HDE trade association).

Perhaps the logic that an intervention that stimulates competition dampens competition will become clear to me after a longer period of reflection – learning curve. If this is not the case, I blame the HDE position on the fact that the large retailers, which apparently set the tone in the HDE, perhaps see their little group as potential candidates for pro-competitive intervention. After all, the federal government has hinted at this in its coalition agreement (p. 37).

The next amendment around the corner?

As far as the coalition agreement is concerned, Gerald Ullrich (FDP) had a little surprise in store during the Bundestag debate. He said that the coalition agreement had actually been over-fulfilled and that he therefore assumes that there would be no further amendment of the competition act in this legislative period. Can Team Giegold drop its pen for the time being? Not so sure – in my reading of the coalition agreement there are still competition law issues that have not been settled with the 11th amendment: Integration of sustainability, powers for consumer protection, reform of ministerial authorisation. Oh, the next season will be entertaining!

Eating cake

Presumably, the people involved from the Ministry and the Bundestag will first treat themselves to a piece of cake on the Ku’damm, just like Emil and the detectives after they had finished off Grundeis. For that, three little icings on the cake:

- Minister of Economics Dr Habeck is not a historian, but he is a literary scholar. He had said in the debate: “Mothers and fathers of the economic-political order of the Federal Republic” had written the GWB as the basic law of the market economy. I am under the impression of a remarkable editorial on the topic of “feminist competition law” in the journal NZKart by Katrin Gaßner and Thomas Lübbig, and so the question arises in my mind: Were there “mothers” of the economic order in Germany? So far, the Freiburg School of ordoliberals has seemed rather male-dominated to me. Hints welcome!

- The Süddeutsche Zeitung reported an interesting detail on the last ministerial approval of a merger that had been banned by the Bundeskartellamt. The Ministry (then led by Merkel’s Peter Altmaier) had trumped the Bundeskartellamt’s prohibition of the Miba/Zollern bearings merger on grounds of public interest. It had set as a condition that the parties involved were required to invest EUR 50 million in the joint venture in Germany. According to the newspaper (and reported on Super Tuesday), this condition is said to have been partly fulfilled by buying companies from the parent company. Oh. More detailed clarification of this affair: Unfortunately not – business secrets.

- On Super Tuesday, the new report of the German Monopolies Commission also arrived in due time. Its core statement: Deutsche Bahn must be split up. This could even be done without recourse to Section 32f of the GWB, since the owner is, appropriately enough, the legislator himself. The Commission published its damning report on the German railway sytem with the headline “Time to GO”, a request that some would like to address to the management of Deutsche Bahn, but which unfortunately is also addressed by Deutsche Bahn to its customers from time to time (then in the variant: Time to WALK/FLY/DRIVE/USESCHIENENERSATZVERKEHR).

ECJ: Mega Mega META

Another topic. The European Court of Justice has ruled on the case that has thrilled this blog for years. The decision, a response to the questions referred by the Higher Regional Court of Düsseldorf in the Facebook case of the Federal Cartel Office, leaves nothing to be desired in terms of clarity. The Grand Chamber of the ECJ (15 judges!) chaired by President Koen Lenaerts obviously wanted to set an example. From the point of view of antitrust law, the Court held that competition law in the digital age does not work in isolation:

“As pointed out by the Commission, inter alia, access to personal data and the fact that it is possible to process such data have become a significant parameter of competition between undertakings in the digital economy. Therefore, excluding the rules on the protection of personal data from the legal framework to be taken into consideration by the competition authorities when examining an abuse of a dominant position would disregard the reality of this economic development and would be liable to undermine the effectiveness of competition law within the European Union.” (para. 51)

It is a matter of course that the competition authorities, when they examine data protection, must then coordinate with the data protection authorities. What is not self-evident is that the ECJ itself has already subsumed how this was done in the specific case – some may still remember the probing questions in the oral proceedings when the Bundeskartellamt’s team (Jörg Nothdurft, Konrad Ost, Irene Sewczyk and Julia Topel) had to explain again and again when exactly they had communicated what with which data protection authority. The answers seem to have been convincing: “The Federal Cartel Office appears to have fulfilled its obligations of sincere cooperation with the national supervisory authorities concerned and the lead supervisory authority.” (para. 61)

The low-data variant

The Bundeskartellamt’s examination concept is confirmed again towards the end of the ECJ decision. In the case of a dominant company, there could be a clear imbalance between platform and user. And further:

“Thus, those users must be free to refuse individually, in the context of the contractual process, to give their consent to particular data processing operations not necessary for the performance of the contract, without being obliged to refrain entirely from using the service offered by the online social network operator, which means that those users are to be offered, if necessary for an appropriate fee, an equivalent alternative not accompanied by such data processing operations.” (para. 150)

The rapporteur, the Italian judge Lucia Serena Rossi, has apparently read the commentary on the Digital Markets Act. According to Art. 5 para. 2 DMA and Recital 37, the user must have the specific choice of selecting a variant that requires little personal data. This applies not only to Facebook or Instagram, but to all core platform services that are covered by the DMA – we will see which ones in a moment. In any case, Google Search is one of them.

Data protection service

Wait a minute, those in the know will now say, even if consent may be difficult, there is still the possibility of other permissions to collect data! Correct. But this is where the ECJ decision really comes into its own. The judges in Düsseldorf, who brought the case, had inquired into the interpretation of Articles 6 and 9 of the GDPR, and in doing so, they have done the data protection lawyers a longed-for great service. What the ECJ is establishing here has disruptive potential for the digital economy. The requirements for the collection of data covered by Art. 9 GDPR, i.e. particularly sensitive data, are formulated strictly. Example: Anyone who calls up a queer website and is subsequently sorted into the advertising marketing category “queer” will presumably be the victim of a data protection violation – unless the person has given explicit prior informed consent on the basis of explicit information. According to my layman’s assessment of data protection law in the parallel sphere, these requirements are likely to be fulfilled rather rarely in practice.

And this also applies to the facts of Art. 6 of the GDPR, which provides for several exceptions. Every conceivable justification that Meta had put forward in the proceedings to justify the building of super profiles is brushed aside. For example, the weighing of the legitimate interests of the user and the platform according to Article 6(1), subparagraph 1(f) of the GDPR is in favour of data protection in the case of financing: It must be assumed that the interests and fundamental rights of the user outweigh the interest of the platform operator in personalising advertising and thus financing the service (para. 117). I am not sure whether all Instagram users would agree with this vote if they were faced with the choice of comprehensively disclosing their data or paying something for Insta – but so far they are not faced with this choice either. This is data protection law with claws and teeth!

More rounds

The ECJ decision is a clear victory for the Federal Cartel Office. It would be incomprehensible if the Office did not now finally demand radical steps from Meta. After all, the highest courts have now blessed the enforceable decision from 2019. The first implementation measure presented in a media release in June – the creation of individually controllable user accounts – is unlikely to suffice, especially if it is hidden behind a few clicks somewhere in the settings menu. However, the office can of course take another year. Then Article 5 (2) of the DMA will apply and the Bundeskartellamt’s Facebook decision, which will then never be implemented, will go down as a significant footnote in its legislative history.

Little Tuesday, by the way, the one from Emil and the Detectives, was played in the film by Hans-Albrecht Löhr, who got the part after sending Erich Kästner, the book’s author, fan mail. In it was the unmistakably beautiful sentence: “It was a corky book.” (Not sure whether this correctly translates into English…) The ECJ decision definitely deserves the title “corky” as well.

DMA: The Seven

On Super Tuesday, it became known which companies see themselves as gatekeepers in the sense of the Digital Markets Act (DMA). There are just seven companies. The seven dwarfs? The Magnificent Seven? The seven deadly sinners? In addition to the usual suspects, i.e. Apple, Amazon, Meta, Alphabet and Microsoft, they also include ByteDance (TikTok) and surprise candidate Samsung. Not listed: Booking.com, Airbnb, Spotify, Oracle, Netflix, SAP, Vivendi, Zalando, Paypal, Zoom, Salesforce, D-Kart, Uber, Verizon – and whoever else was floating through various lists. In the meantime, there was talk of 10, 15, 20 gatekeepers. Now, in the first attempt, there are only 7.

How is this to be interpreted? I have three readings on offer:

- Bubble variant. Quantitative key figures are what count most in determining the gatekeeper: 7.5 billion EUR in turnover or an average market capitalisation of 75 billion EUR, at least 45 million monthly active end users and at least 10,000 annually active business users, all in three consecutive business years. Are some of the big things on the internet just a soap bubble that bursts when you take a closer look at the figures? Hype, hype.

- Tea-drinker variant. All those who have not come forward would have to be nominated by the Commission. This is costly. The DMA team is probably already well in work with seven gatekeepers. So if there is at least a legal doubt here or there as to whether one really meets the criteria, one could first sit back, wait and see: let the COM come. This would fall into a strategy that pessimists expect for the DMA anyway – no nerdy compliance participation, thereby overburdening the Commission, which is hardly equipped for a real confrontational approach.

- Oligopoly variant. In addition to creepy TikTok and the candidate that came out of the darkness, Samsung, this is the well-known five GAFAMs. They have, after all, been the focus of attention since the beginning of internet criticism. And perhaps the critics have always been right: the internet is ultimately run by these companies – and the others that hang around the edges of the five-headed hydra of the five-headed monopoly bloc are not infrastructure providers of the digital economy after all.

Which of these readings is correct and what the Commission makes of it is open. Perhaps it is also a very good thing that it can concentrate on the top 7 for the time being and not have to deal with a multitude of companies straight away.

We know that we know nothing

What is already certain, however, is that transparency is low and the forecasting skills of the think tanks are meagre. The fact that the gatekeeper reports became a surprise actually shows how little is still known about these companies that have been in the spotlight for years. Samsung, by the way, is an interesting example in this respect. Even the day after, no one really knew what core platform services Samsung actually provides. Suspicion: the academic elite that deals with big tech criticism doesn’t use Samsung phones and therefore doesn’t know anything about them (they run Android, by the way, but there is a separate Samsung app store and browser). Is it possible that the age-old accusation is true that enforcers and policy-makers are best able to think their way into their own everyday problems, i.e. into their iPhone lock-ins?

Incidentally, the Meta Group has not rolled out its new “Threads” feature in Europe for the time being. According to Politico, Threads is “a poor man’s version of Twitter circa 2011”. Copy & paste is one of Meta’s strengths. In any case, Twitter has already taken steps to defend itself against the imitation of its service, as can be read on, well, Twitter. The fact that Meta is able to immediately enter the Twitter business with a relevant user base thanks to its tie-up with Instagram speaks volumes. The mastodon cries silent tears behind its big trunk.

However, the reason for the reluctance with the new feature in the EU is probably digital rules, even though the Irish Data Protection Authority, which has been in contact with Meta, has – surprise – not opposed it. So is European digital regulation working and saving us from a new annoying social media channel? Those who regret it (eg for lack of competition for Twitter), be comforted: You have D’Kart! Not just on a little Tuesday, but every day of the week at www.d-kart.de.

Have a nice weekend!

Prof. Dr. Rupprecht Podszun is co-director of the Institute for Antitrust Law at Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf and editor of this blog.