AGENDA 2025: Time for a Comeback? The Case for Structural Antitrust

This article is part of the D’Kart Spotlights: AGENDA 2025, in which experts from academia and practice comment on aspects of the Competition Policy Agenda presented by the Federal Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK). The contributions already published can be found here.

Many have hoped that big companies would be disciplined by competition. For Dominik Piétron the opposite is true. Corporations have become increasingly powerful and developed new tools to impose private arbitrariness. To effectively protect society from economic oligarchs, anti-trust must address the structural causes of market power – as proposed by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action.

There is no doubt, market concentration has increased in the past decades. Large firms owe their expanding empires as much to technological progress as to ineffective antitrust legislation, excessive intellectual property protection and aggressive merger and acquisition strategies. Over the past 35 years more than one million merger and acquisition (M&A) deals have been completed globally (Khan/Vaheesan 2016). Mergers and acquisitions in 2021 saw the highest deal value in history. Intense lobbying by the patent community has been a major force driving the consolidation of market power, along with regulatory capture by large corporations. The vicious cycle of market power begetting political lobbying power has meant that the economic underworld of corporate rent-seeking is becoming legitimate, systematically contributing to rising income inequalities and power imbalances in the global economy.

The social and economic consequences of this concentration of economic power can no longer be ignored: Since ownership of companies and shares are very unevenly distributed, profits mostly end up in the pockets of owners, investors, and managers. Asset management firms holding many shares of corporations across the sector are driving listed companies to increase their returns and to follow aggressive M&As pursuing this goal. Powerful companies can increase their margins by forcing suppliers to decrease prices, controlling market access, and leveraging economies of scale. It is mainstream economic thinking that rising market power has led to extraordinary profits of powerful corporations, falling labour income shares, lower investments, and lower output.

This is particularly evident in the digital economy, in which platforms give rise to a new type of “monopsony” power. Due to their market power, Internet corporations such as Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta but also smaller platform companies like Spotify or Booking have become the gatekeeper for company that wants to offer digital content, services, or products to consumers. Based on their power to control access to proprietary marketplaces they can define the market rules, prefer their own products and extract valuable market intelligence. They pressure their business users, dictate prices, influence their customers’ purchase decisions and even copy profitable products. Even niche platform companies such as Booking or Spotify employ opaque algorithms making it particularly difficult to supervise and regulate these empires. Driven by large venture capital funds, they invest large sums to subsidize their prices, prevent potential competition and consolidate their market position by buying up innovative newcomers.

It is often forgotten that it was a structural intervention by the U.S. antitrust authority that paved the way for BigTech. By breaking up America’s monopolistic telecommunications provider AT&T in 1983, the U.S. antitrust agency cleared the market for digital newcomers, which subsequently developed into powerful platform companies like Google and Apple (Kushida 2015). Since then, however, the Chicago School of Antitrust gained prominence and started to weaken effective antitrust law. The Chicago boys and their descendants have subverted the traditional goals of antitrust such as dispersion of power, and instead promoted corporate concentration and returns to shareholders while facilitating the appearance of big players. Rather than prohibiting dominant positions, Chicago Antitrust only ruled out the abuse thereof, thereby potentially allowing for significant degrees of concentration. The paradigm shifted to price theory, which increasingly made business efficiency and consumer welfare the sole decision-making criteria. As a consequence, the balance of power has obviously shifted in favour of international corporations and particularly the financial sector, at the expense of smaller and nationally oriented businesses and labour.

“We’re now 40 years into the experiment of letting giant corporations accumulate more and more power (…). I believe the experiment failed“

(US-President Joe Biden, 2021)

“For this reason, the GWB Novelle is intended to create an break up option that is applicable irrespective of a proven violation of antitrust law“

(German Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, 2022)

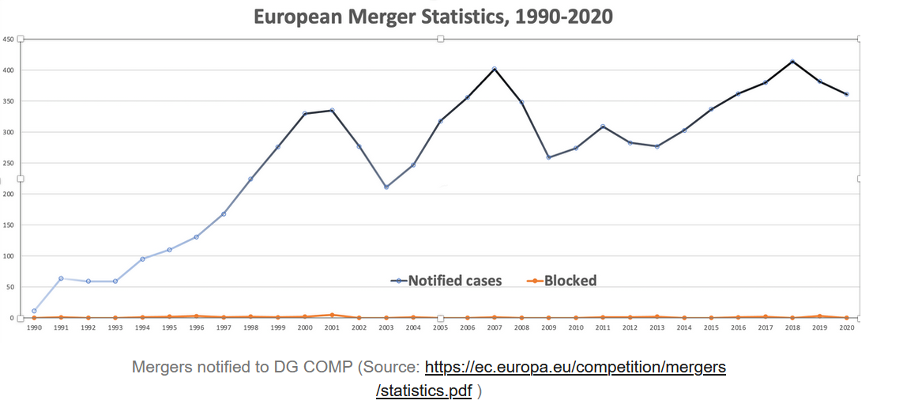

What is the European response to excessive market power? The EU Commission is “possibly the strictest and most efficient antitrust institution” however, their cases on abuses of dominance – such as the ones on Google – did not lead to any significant changes in the structure of markets or how they operate. The Digital Markets Act provides a set of rules for economic gatekeepers, but applies only to the digital economy and even there fails to address the underlying economic imbalances that enable structural abuses in the first place. In fact, when it comes to structural measures against vertical integration and vertical mergers, the EU Commission has taken a pro-concentration stance in competition policy. Out of the roughly 15,000 mergers every year, 400 transactions are notified to the Commission, maybe 30 go into a deep assessment, maybe 15 get some remedies, and often none are blocked. Here, the historical path dependency of neoliberal competition policy becomes apparent. When the Commission announced its plan for adopting merger rules in 1985, for example, it assured business organisations like the European Roundtable of Industrialists (ERT), UNICE (today BusinessEurope) and AmChamEU that it would not take the line “that bringing the big together is bad” (Wigger/Buch-Hansen 2011). Instead, the Commission refers to synergy effects, such as lower costs and thus lower prices for consumers, product innovation and the displacement of inefficient management structures. Moreover, Executive Vice-President Margarete Vestager has repeatedly refrained from curtailing the powerof large technology corporations through “structural separations”. It maybe that the EU-Commission doesn’t see any need to change its stance.

In order to challenge competitions’ supremacy over social and environmental aspects and to create fair market structures, mental and political shifts are needed. It all depends on EU parliament, member states and civil society asking for stricter competition rules to address rising market power in the EU. One option is that the new German government takes the initiative. Its coalition agreement as well as the new “Wettbewerbspolitische Agenda“ of the German Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action are committed to strengthen merger control and the break-up option at European level. Recently, German Economics Minister Robert Habeck reiterated his ambitions to reintroduce structural antitrust measures and argued for abuse-independent break up instrument. Together with an alliance of European countries like France, there might be a chance to enlarge the competition review agenda of the Commission.

The US is an inspiring example in this regard. Under the Biden administration, we can currently observe a comeback of the market structure-based understanding of competition, for example in the work of the Federal Trade Commission on stricter guidelines for merger controls. The basic idea of structural antitrust, which formed the basis of antitrust thinking and action up until the 1960s, is that concentrated market structures promote anticompetitive forms of conduct. This view holds that a market dominated by a very small number of large companies is likely to be less competitive than a market populated with many small- and medium-sized companies. This is because (1) monopolistic and oligopolistic market structures enable dominant actors to coordinate with greater ease and subtlety and because monopolistic and oligopolistic firms can (2) use their existing dominance to block new entrants (3) have greater bargaining power against consumers, suppliers, and workers, which enables them to hike prices and degrade service and quality while maintaining profits (Khan 2017).

With this in mind, civil society organization in Germany and the EU as well as the European Parliament demand stronger structural antitrust instruments to protect people and the planet from excessive corporate power: On the one hand, stronger merger controls need many improvements, of which we can only name a few. First, purported efficiencies should not factor into merger review decisions, instead structural presumptions on data / market concentration and buyer power as well as on considerations on the externalization effects of social and environmental costs should be introduced. Second, the burden of showing that a merger is unlikely to negatively impact the broader economy and to restrict potential competition should fall on the parties whenever there is a realistic prospect of such a restriction occurring. Third, killer acquisitions must be prevented, even if the company to be acquired is still below the threshold of market dominance. Many other proposals are on the table.

On the other hand, it is time for an explicit abuse-independent break-up instrument for companies with cross-market power as proposed by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action. Structural separation has been discussed several times in certain sectors, such as telecommunications, energy and railway. Especially in the digital economy, where companies tend to form cross-market ecosystems, the structural separation of companies must be part of the standard toolbox of competition authorities. There is no known example of such a split having a negative impact on the market. Instead, breaking up companies after consummated mergers is a common economic practice and can certainly be a success. The breakup tool should be used primarily in serious cases where corporations’ power threatens fair business operations and democratic control, such as with Google Search/Android, Instagram/WhatsApp/Facebook or the various divisions of Amazon. This way, such an instrument will also have a disciplinary effect beyond individual cases. Breakups do not replace regulation. But they address one fundamental issue: the concentration of economic power and the resulting imbalances.

Dominik Piétron is a researcher at the Institute of Social Sciences at the Humboldt University of Berlin and conducts research in the field of ‘Political Economy of Digital Capitalism’.

One thought on “AGENDA 2025: Time for a Comeback? The Case for Structural Antitrust”

Ein interessanter Artikel. Mir stach insbesondere dies ins Auge: “Um die Vorherrschaft des Wettbewerbs über soziale und ökologische Aspekte in Frage zu stellen und faire Marktstrukturen zu schaffen […]” Ich sehe eine gewisse Mode, Wettbewerb einerseits und soziale und ökologische Belange andererseits als unvereinbare Gegensätze darzustellen. Z.B. sollen Absprachen zu ökologischen Zwecken zulässig werden. Es wirkt so, als könnte der Wettbewerb bei ökologischen Belangen nicht helfen. Dabei dürfte das Gegenteil der Fall sein. Wettbewerb um besonders umweltfreundliches Verhalten dürfte hilfreicher sein als zweifelhafte Tierwohl-Labels (da bin ich bei Herrn Haucap und dem Kronberger Kreis). Der Gesetzgeber müsste sich entsprechend statt auf den Abbau des Wettbewerbs darauf konzentrieren, die Kosten umweltschädlichen Verhaltens bei den Verursachern zu internalisieren. Auch der Widerspruch zwischen Wettbewerb und sozialen Fragen überzeugt mich nicht. In Volkswirtschaften mit funktionierendem Wettbewerb geht es allen sozialen Schichten besser. Und die Beschränkung des Wettbewerbs wird schwerlich zu faireren Marktstrukturen führen. Die Einhegung von Big Tech erfordert auch keinen Abbau des Wettbewerbs. Es geht vielmehr darum, den Wettbewerb wieder herzustellen bzw. zu schützen. Mancher Ökonom sieht dort einen Widerspruch, weil Unternehmen keine Anstrengungen mehr im Wettbewerb unternehmen würden, wenn das Monopol nicht als Lohn winke. Das überzeugt mich nicht. Für viele Unternehmen liegt die marktbeherrschende Stellung in unerreichbarer Ferne, trotzdem liefern sie harten Wettbewerb.