Refill: Beer Cartel (da capo)

Hello again! The parties involved in the German beer cartel are meeting in court again. The Cartel Senate of the Federal Court of Justice called for another round by overturning an acquittal of the Düsseldorf Higher Regional Court in this case in 2020. Now other judges of the Düsseldorf Court have to take up the matter. Rupprecht Podszun, who had written about the first proceedings here, has followed the new start of the trial.

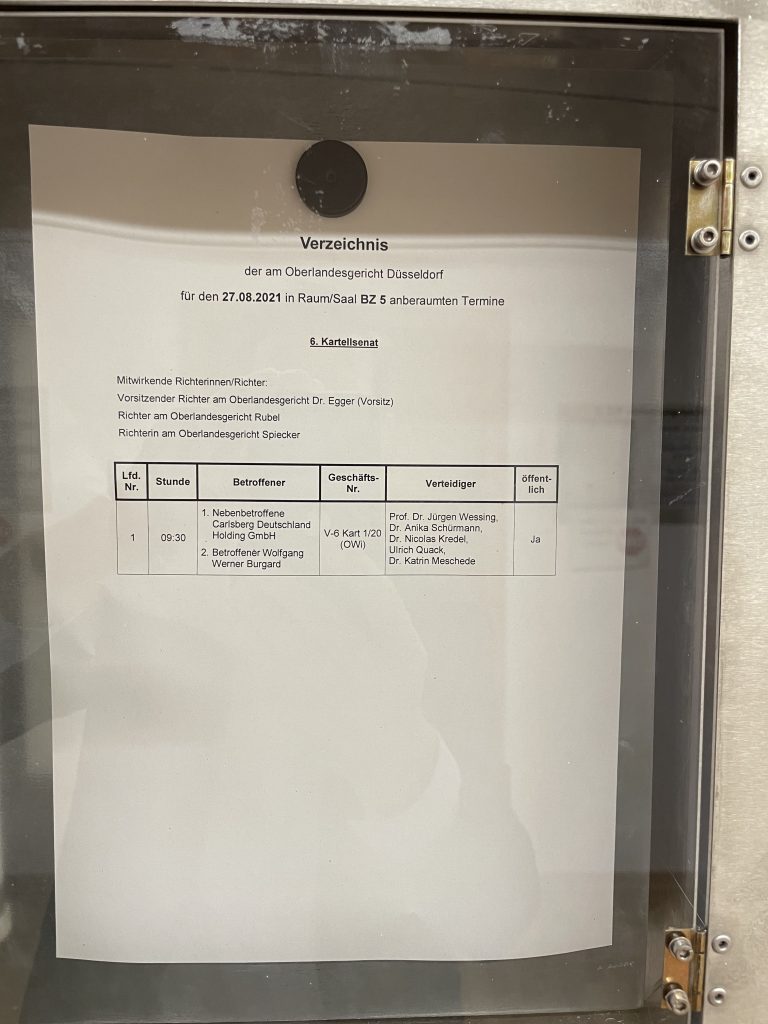

“We are new! Let’s start again with an open mind!” exclaimed the presiding judge Ulrich Egger about half an hour after the beginning of the trial. However, there was no real excitement in room BZ5 of the Düsseldorf Higher Regional Court, the Oberlandesgericht. If it were customary to heckle in court proceedings, someone on the left would certainly have shouted: “But we are not new!” On the left side of the courtroom (seen from the spectators’ chairs), however, only sat soigné gentlemen, who – as should be shown later – can be quite sharp in their remarks. But they prefer to direct them against the right side than against the bench, on which a lot depends.

This lot is worth 62 mio. € – that is the fine imposed on the Carlsberg brewery (Holsten, Astra, Duckstein and others). Another, much smaller fine is at stake for its then managing director in Germany, Wolfgang Burgard. Except for Carlsberg, all breweries had accepted their fines and withdrawn appeals in the German beer cartel shortly before the first trial of this case began. Carlsberg stood firm and was initially rewarded: because of the statute of limitations for prosecution, the 4th cartel senate of the Düsseldorf Higher Regional Court had handed down an acquittal. But the Supreme Court, Bundesgerichtshof, overturned this decision and referred the case back to Düsseldorf. It is now the sixth cartel senate of the Oberlandesgericht that is in charge. The reversal by the top court was sobering for the team that had won at the first attempt. Now, everything starts afresh, and so we will see a lot of double in the coming months.

In the repeat loop

The exclamation by presiding judge Egger occurred while discussing a problem that, in the form of a small procedural issue, sums up the great discomfort with the process. Let’s call it the “Restorff effect” (even though this name actually refers to something else in psychology). The Restorff effect of the beer cartel trial ties back to the status of witnesses: Is a witness who at the same time represents the company in the dock authorized to sit through the proceedings? Actually, it is not supposed to be the case that witnesses follow what is going on, but this representative, Matthias Restorff is his name, is the legal counsel of the Carlsberg brewery. He has already heard all of what is presumably being performed a second time – he was also in the courtroom throughout the first Düsseldorf trial. He is apparently still to be heard on compliance measures during the course of this repeat trial, but he also follows the proceedings on behalf of his employer. The senate has doubts: “If, after several months of hearings, I hear a witness who was there the whole time…” – Dr. Egger leaves the sentence unfinished. Lawyers for Carlsberg: “But he was already present during Winterscheidt’s trial!” That’s the crux of the matter: the parties on the left and right are stuck in a groundhog day loop. They have already spent 27 trial days before the 4th Cartel Senate under Manfred Winterscheidt, before that they had to report to the Federal Cartel Office – and before that the events that are now once again at issue also took place in reality. Or not. Only the judges in the courtroom are new and unbiased: Dr Ulrich Egger as chairman, Stefan Rubel as rapporteur, Vera Spiecker as associate judge.

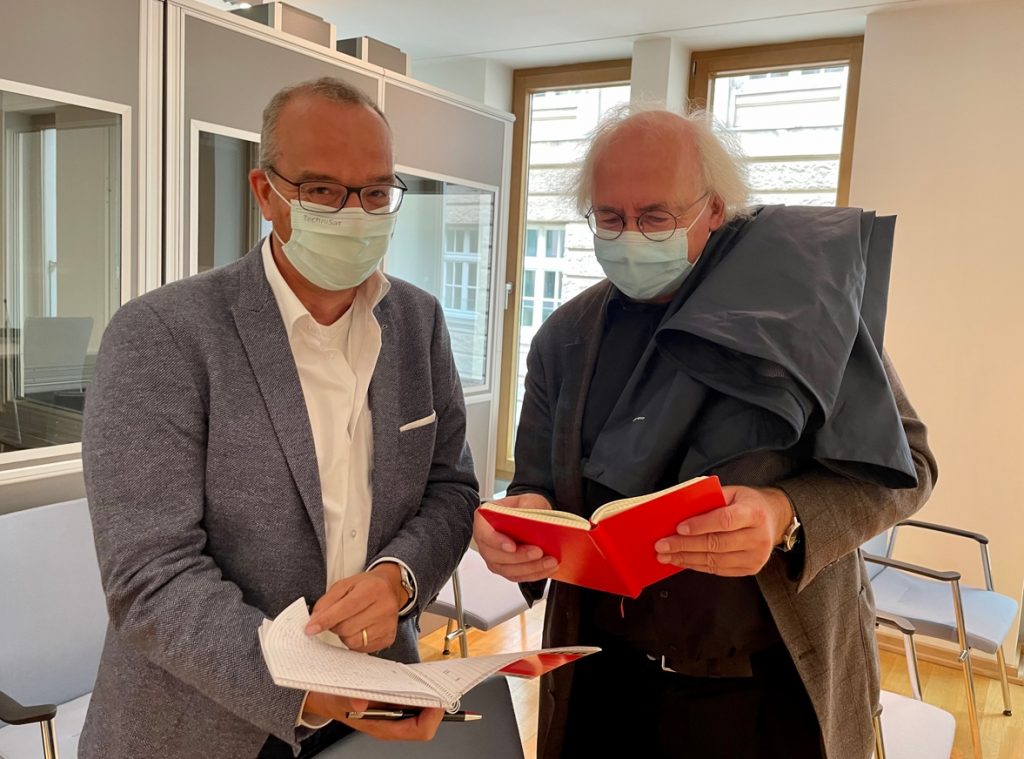

So should Restorff perhaps be allowed to stay in the room after all? Attorney Jürgen Wessing, a veteran of the white-collar criminal defense scene, declares to the Senate in a moment of silence: “Mr. Schmitt thinks you might allow.” Wessing, the pro, says this in a voice as if he had just received a call from God, who had thus blessed Restorff’s whereabouts. For a brief moment, Judge Egger also seems to doubt incredulously whether there isn’t an authority above his Senate besides the Bundesgerichtshof, named Mr. Schmitt. But then everyone goes ahhhh: We are talking about Bertram Schmitt who wrote on this issue in a well-known book on criminal proceedings. Wessing’s maneuver doesn’t catch, but the court finds a comfy solution: Restorff will be questioned in the trial next week.

The beginning of a long journey

The Senate has scheduled 33 days of hearings, but it wants to finish this year. It’s going to be a long journey, and Judge Egger is the tour guide. He’s very friendly, very approachable to everyone on this first day of trial. He toils like a motivational teacher in front of a group of bored students who now have to go to a museum, even though they’d much rather be lounging around the lake with a six-pack of beer. When Ulrich Quack, defender of the former Carlsberg managing director, asks very politely whether he has to travel from Berlin for all the hearings (“in these times!”), Egger looks as if he wants to say: “I know, Uli, but we only get the subsidies for our trip if we also go to that museum.” The point: Everyone – but Egger and his colleagues – had been to that museum before.

The cultural programme begins with the reading of the fine notice from 2014 by Dr. Jan Steils, representative of the Attorney General’s Office. Next to him sits Markus Rauber from the Federal Cartel Office, the Bundeskartellamt, behind him is Andrea de Lagaye de Lanteuil. Her job title “Public Prosecutor at the Federal Cartel Office” is remarkable. When taking the attendees to the minutes, however, Egger rather stumbles over the correct pronunciation of the surname: “Only had two years of French”, he mumbles, and one may assume that it was not his favourite subject. The Cartel Office put it succinctly. The core accusation: Carlsberg was involved in the beer cartel of the large Pils breweries. The starting point for this was a meeting on 12.3.2007 in a Hamburg hotel “on the occasion of the Internorga”. (This phrase – “on the occasion of the Internorga” – comes up so often that for antitrust lawyers the Internorga gastronomy trade fair is probably only ever relevant “on the occasion”).

The presiding judge now clarifies that the first ruling of the Oberlandesgericht Düsseldorf, the Winterscheidt one, is legally void due to the ruling of the Bundesgerichtshof. The judges now are not bound by it. He looks piercingly at the eight people watching the trial while making this statement. He uses the look that professors sometimes have when they warn students not to make that one fatal mistake. If you do you should burn in hell.

The price of the rule of law

Then the 37-page Bundesgerichtshof ruling is read out. Stefan Rubel is the first to read, after half of it Egger relieves him. Judge Rubel does it really well! It’s great to listen to him, he emphasizes in such a way that one can follow the explanations wonderfully. Anyway, this bench has a sympathetic aura. Judge Spiecker does not wrap herself in the apathy of a bored associate judge, as is sometimes seen. She goes along with the proceedings, even laughs once in a while when it suits her. As a team, the three of them now want to deal with a trial they didn’t ask for and which is actually an imposition for everyone involved, but they don’t want to let that show at any price. The lawyers for Carlsberg – in addition to Quack and Wessing, the latter’s colleague Maximilian Janssen has also appeared – have to hope that in the repeat match they will manage another coup like the first time. (Incidentally, the company has remained loyal to Baker & McKenzie as well as Wessing, although part of the Baker team has moved to Mayer Brown. ) Unpleasant questions could arise for the Federal Cartel Office. And in the coming weeks, current and former managers of the beverage industry will take the witness stand who have already been through all this before and are now supposed to remember a meeting “on the occasion of the Internorga” and subsequent bilateral contacts which meanwhile happened fourteen years ago.

The reading of the BGH ruling is a visible expression of an insane effort for the rule of law. It does not ask for time, costs and sense of such a repetition game. The parties involved have probably already turned over every comma of the now time-consuming read-out decision three times. They could now play Candy Crush (as German politicians when discussing Corona measure as was revealed by one prime minister) but they take the dignity of the place more seriously. Checking e-mails is not really possible either: Internet is lousy in this wing of the building. Even the journalists have worked through the BGH ruling in advance and marked it with different colours – admittedly, they are two impressive antitrust experts, Erich Reimann of dpa and Hanno Bender from Lebensmittel-Zeitung.

At least not triple digits?

After a short break, something of a scoop does come: Judge Spiecker reads out a note of a preliminary meeting that took place on 13 April this year “from 10:01 am to 11:15 am.” For observers, this is a welcome glimpse into what will unfold in the coming weeks. There has been no deal in the process, with views irreconcilably opposed. The evidence is thin, attorney Quack is quoted as saying, who was apparently digitally connected (at least once). Egger let it be known in the meeting that the meeting “on the occasion of the Internorga” is likely to be decisive. Also the question of the statute of limitations is apparently not yet off the table for him. And then: A fine in the three-digit million range – as most recently demanded by the public prosecutor’s office in the trial – is not conceivable.

So it is becoming apparent that all the managers will have to dig into their memories to reconstruct what happened “on the occasion of Internorga” (hereinafter: otooI). At the Federal Cartel Office, which closed the case with the help of leniency applications (AB InBev came out of the proceedings without a fine), investigators were convinced that the managers decided to agree on a price: 1 euro more per crate. At the beginning of 2008, the Office writes in its case report, “there was again an almost nationwide price increase for bottled and draught beer in Germany. ” Attorney Wessing later presents the matter differently: The otooI meeting had been “a talking shop which did not advance anything”.

Social gathering

As an unbiased observer who naively believes in the principle of competition, one is always amazed by the sociability of company representatives for whom it is apparently a matter of course to meet with the competition instead of tackling it. “Compliance” still seemed a strange animal otooI in the fiftieth year after the introduction of competition law in Germany. On the other hand: the SIDE Hotel in Hamburg on the Gänsemarkt looks good, the bar there serves Radeberger and Duckstein beers these days. People like to get together there, perhaps also to fight the hangover in the industry: beer consumption was falling in 2007, costs were rising, and some CEOs were under pressure from their corporate groups. Of course, this is no excuse for an alcoholic fraternization.

The requirements of the BGH

Without the otooI meeting, the antitrust world would have missed out on an interesting decision by the Supreme Court (BGH). The judges with Chairman Professor Peter Meier-Beck apparently saw it similarly; the decision has been scheduled for reprint in the official collection BGHSt, which is not the rule. The first guiding principle (“Leitsatz”) reads:

“The offence of concerted practice is twofold; it requires, in addition to a coordination process (contact), an actual conduct in the sense of a practical cooperation on the market, i.e. a concrete market conduct in implementation of the coordination. A typical means of prohibited coordination is the exchange of information on parameters relevant to competition with the aim of eliminating uncertainty about the competitor’s future market conduct.”

To this end, the BGH offers some clarifications as to what constitutes coordination within the meaning of Article 101(1) TFEU. Ultimately, it is the exchange of information that so often causes headaches in antitrust law: Has this already been a coordination? The BGH does not set particularly high standards here. The 4th Cartel Senate of the Düsseldorf Higher Regional Court had overstretched the requirements, so the BGH says. The exchange of competition-sensitive information is a typical contact which is sufficient for contact. An “expectation of coordination” does not have to go hand in hand with this. This is entirely in line with the strict view expressed here that it is not appropriate to “chat” with competitors. Even an exchange of information that ends “openly at the end” is such a contact.

The implementation and its proof

In the second step, however, the BGH requires an implementation in the form of a causally brought about concrete market conduct. What is required is “conduct downstream of the coordination process on the relevant market affected by the cartel […], which does not cover mere communication between undertakings”.

So the CEOs are allowed to chat with each other. If the exchange of information remains without any consequences, there is no violation of antitrust law, as the Federal Court of Justice explicitly states:

“Insofar as the Higher Regional Court assumed that the ‘attempted coordination’ aimed at an agreement in violation of cartel law, which was to be seen in the meeting of 12 March 2007, fulfilled in itself the constituent elements of a concerted practice within the meaning of Article 81 (1) of the EC Treaty and Section 1 of the German competition act, the judgment contains an error of law detrimental to the persons concerned (Section 301 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, Section 79 (3) sentence 1 of the Code of Administrative Offences).”

As is so often the case, this thorny issue is overshadowed by questions of proof. For it is of course part of “economic empirical knowledge that an undertaking normally takes account of knowledge of intended or contemplated market conduct of a competitor when determining its own market conduct” (BGH). Anything else would be unrealistic. But how far does it follow that there is a presumption, or even an obligation, to provide evidence to the contrary for the companies that have talked about prices?

Caution, principle of guilt applicable here! The BGH states that according to the principle of guilt, the full conviction of the trial judge is required; there are no exceptions to this. But there is an “indication”, whatever that means exactly, and this “all the more so if – as here – competitors, after having discussed a coordinated course of action, promptly engage in similar conduct towards each other”.

Another flower of this procedure is that the market behavior can apparently be read from the news. Mr Rauber of Bundeskartellamt announces they will present documentary evidence in the form of the journal “inside Getränke”. According to the Bundeskartellamt’s reading, the price agreement was communicated there to the public. Public announcements of raising prices – information exchange at the limit.

Who was there

That is the tricky conundrum now facing the three judges: are they convinced – after taking evidence – that the exchange of information was reflected in Carlsberg’s pricing?

Wessing & Co. want to make this a little more difficult for the court. Wessing, who, by the way, is also an honorary professor at Heinrich Heine University in Düsseldorf, makes an “opening statement” pursuant to § 243 (5) sentence 3 of the German Code of Criminal Procedure (StPO) that is quite something. He questions whether Wolfgang Burgard of Carlsberg was even present at the meeting otooI. Later contacts in smaller groups are possibly not particularly well documented, which would lead to the fact that the accusation would stand on shaky legs. Wessing does not commit himself at all. The phrase “Burgard was not present” does not come up. Wessing knows what matters: Can it be proven?

Of course, Burgard does not make any statements on the matter. One would now like to politely tug at his brown jacket and ask: Where were you on that 12 March 2007? If up to this point one still had a certain pleasure in the legal gymnastics of criminal law, frustration now follows. What if Burgard really doesn’t even remember himself? It would be quite understandable, it was a long time ago and meetings between competing brewery directors seem to be nothing unusual.

A serious accusation

Whether the defense strategy will work depends on statements made by top management of other breweries in leniency applications and settlement documents. They led to Carlsberg now being on trial. Wessing claims that the Bundeskartellamt “at least unconsciously” influenced the testimony. It is getting uncomfortable in the courtroom of Dr. Egger now, who after all was trying to keep a good mood.

Wessing literally:

“There has been evidence of unrecorded assistance. Affected people have also been pressured. They have stated things in leniency applications and settlement that they themselves were not aware of.”

Such accusations are probably necessary when a fine of millions and victory in a replay are at stake. For a moment, one may ponder the question for whom Wessing’s announcement is actually more egregious: for the investigators of the Federal Cartel Office who, in his view, have flouted fundamental principles of the rule of law? Or is it more embarrassing for the interrogated CEOs who, with their top lawyers at their side, were apparently so soft-boiled by officials in Bonn that they simply signed anything in the end? Cartel Office representative Rauber rejects the accusation. The proceedings were conducted in a “flawless” and “spotlessly clean” manner, the court will be able to convince itself of that.

The court will have its first opportunity to do so after the lunch break. It’s a Friday, 2:00 p.m. Christof Vollmer, who led the proceedings at the Federal Cartel Office, is scheduled to testify that afternoon. Here we go again.

Further articles in our blog on the “beer cartel” can be found here (an assessment by Rupprecht Podszun prior to the first start of proceedings at the OLG), here (on the decision in the 1st trial), here (on an event of the study association on distortions of the fine law by Laura Delgado Pazos), here (on reforms in fining law by Maximilian Janssen) as well as here (Thomas Wostry on investigative powers).

If you don’t want to miss any future posts on D’Kart, you can sign up for our email newsletter here. You will still be asked for a confirmation. Please also check your spam filter. Have fun with D’Kart!

The German language podcast “Bei Anruf Wettbewerb” with Justus Haucap and Rupprecht Podszun is all about the Bundestag elections these weeks. The guests are politicians of the parties with good prospects of forming a government, who talk to the two professors from Heinrich Heine University about themselves and their ideas. The podcast is available at all podcast providers or here.

4 thoughts on “Refill: Beer Cartel (da capo)”

Was mir Gedanken macht: Der Trend zu langen Verfahrensdauern im Kartellrecht setzt sich fort. Was sich bspw. beim Facebook-Verfahren zeigt, gilt leider auch hier. Wir müssen uns ernsthaft Gedanken machen, wie wir gerade im Bußgeldbereich kürzere Verfahrensdauern erreichen können. Wer momentan in diesem Bereich aktiv ist, braucht Ausdauer und ein gutes Gedächtnis.

Die erste Entscheidung des OLG Düsseldorf zum Vorwurf des abgestimmten Verhaltens auf Basis der Vorgaben der Carlsberg-Entscheidung des BGH folgt am 8. September im Bierkartellverfahren Teil II – es ist wieder der 4. Senat am Zug. Lessons learned? Der Grundsatz “in dubio pro reo” muss künftig in der Praxis deutlich mehr Gewicht haben. Es kann nicht sein, dass sich Unternehmen trotz jahrelanger Ermittlungen gegen Vorwürfe verteidigen müssen, die keine klare Grundlage haben. Das gilt ganz besonders für den sehr weitreichenden Vorwurf des abgestimmten Verhaltens.

Großartiger Text. Gerne mehr!!

@Paul Mey: Es gilt hier, was auch sonst überall gilt: Wenn die Ausstattung stimmt, werden die Verfahren kürzer. Alles andere ist Augenwischerei.

Danke für diese amysante Darstellung des doch nicht unkomplzierten Verfarhens. Sie haben mir damit die Stimmung an einen verregneten Nachmittag gerettet.