Market power = relative (also in Switzerland)

Switzerland has – after a long struggle – adopted a new regulation that now also covers relative market power in competition law. It is to come into force in 2022. Patrick Krauskopf and Dominic Schopf explain the new rule and its background.

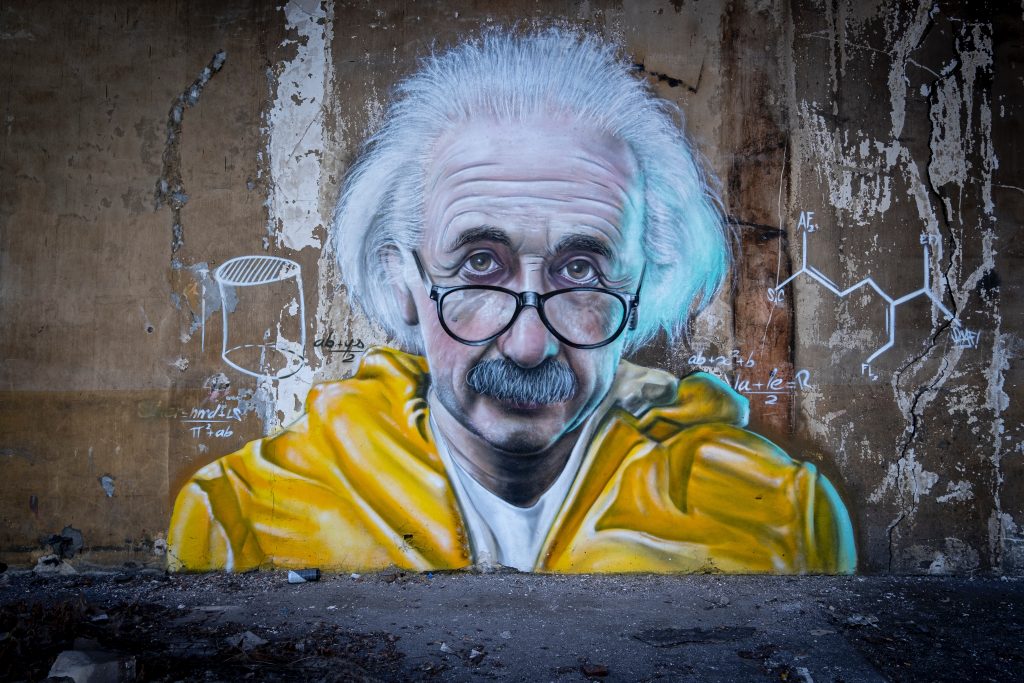

Bern, a City of Relativity

Bern, Kramgasse 49 in 1905: Albert Einstein is about to make a fundamental contribution to basic research in physics. He recognises that space and time are relative to each other and do not represent absolute quantities. His work will conquer the world as the “theory of relativity” (for the sake of physical and, above all, for the sake of legal correctness, which is much more important here, one would still have to distinguish between the “general” and the “special” relativity) and continue to shape it to this day.

Bern, Bundesplatz 3 (Federal Palace) in 2021: Some 116 years later, relativity is once again being “researched” in the city of Bern. Parliament is on the verge of passing a fundamental change in the foundations of antitrust law. 162 (out of 246) parliamentarians recognise that the market positions of suppliers and demanders are relative to each other and that market dominance is not an absolute parameter. Their votes will pave the way for the concept of “relative market power” and hopefully stimulate competition in Switzerland’s small domestic market in the long term.

The (relatively) long road to knowledge

Relative market power – hasn’t it been there before? The introduction of relative market power is of course – and here the antitrust experts from the “big canton” (Swiss for: Germany) will surely agree – overdue. Strictly speaking, it was thought that relative market power had already been introduced on the occasion of the last major competition law revision in 2004. At that time, the definition of a dominant company in Art. 4 para. 2 of the Cartel Act (KG) was amended as follows after extensive parliamentary debates (amendment in bold, full text here (also available in English)):

“Dominant undertakings are defined as individual or several undertakings which, as suppliers or demanders on a market, are in a position to behave to a substantial extent independently of other market participants (competitors, suppliers or demanders). »

A controversial concept from the beginning. The conclusion from some 16 years of (non-)application of the terms in parenthesis: A parenthesis in the article is not enough to introduce the complex concept of relative market power; certainly not in a country that traditionally has a liberal conception of its economic order. Although there are references to the introduction of relative market power in the legislative materials, in particular the accompanying statemtent of the Federal Council (the Swiss government), there has been no lack of doctrinal opinions since the beginning that did not want to know anything about the introduction of relative market power. Other doctrinal opinions, in turn, interpreted the addition in brackets merely as a request to the authorities to define the relevant market more narrowly or restrictively.

Swiss restraint. Due to this shaky legal foundation, relative market power only had had a chance from the outset from an ex post perspective if the Competition Commission (Wettbewerbskommission, WEKO) had taken decisions quickly after the revision of the law in which relative market power was clearly recognised. However, the practice was – and remains to this day – cautious: the WEKO has so far mainly concentrated on further developing the classic concept of market dominance from Art. 4 para. 2 of the Cartel Act and giving economic dependency a place within the boundaries of this concept. Thus, the WEKO has analysed questions of relative market power under the guise of “individual dependencies”. This concept was repeatedly applied to supplier relationships in retail, which is dominated in Switzerland by the two big players Migros and Coop. Here, too, much is relative: the retail giants in Switzerland are faced not only with small suppliers but also, in some cases, with global manufacturers of branded goods. However, the actual introduction, consolidation and development of an independent concept of relative market power similar to the meaning of Section 20 of the German competition act (GWB) has not taken place.

Popular initiative promises lower prices – thanks to relative market power! This development, which many business leaders and antitrust lawyers find timid, was directly addressed in 2017 with the submission of a political initiative called “Stop the high price island – for fair prices (Fair Price Initiative)”; the aim here was to give the WEKO a leg up. The initiative was brought for popular vote (like a referendum). At this point, the initiators of the “Fair Price Initiative” achieved a feat: they knew how to “sexily” (not to say populistically) frame the complex and difficult issue – and they made this topic of relative market power interesting for the average consumer. The following picture is typical for the “packaging” of the initiative – pointing at the differences in price between Germany and Austria:

Victory without a fight: Parliament feels compelled to act. Behind this packaging, as already mentioned, is the explicit idea of placing relative market power into competition law. The initiators of the “Fair Price Initiative” succeeded in bringing this abstract concept closer to the general public by means of examples of price differentiation, especially for branded goods. It is therefore significant that this initiative was given the nickname “Lex Nivea” (Nivea being a major cosmetics brand in Switzerland). In the campaign, which was certainly brilliant from a communication point of view, even the intensive lobbying of the business associations – who said that the initiative was structural policy, not competition policy – could no longer prevent the introduction of relative market power. In the end, parliament passed a so-called indirect counter-proposal to the initiative, which practically adopts all the concerns of the “Fair Price Initiative” and above all the concept of relative market power. At the same time (for the sake of completeness), the indirect counter-proposal includes a ban on geo-blocking in the Unfair Competition Act (Gesetz gegen den Unlauteren Wettbewerb). As a result, the initiators agreed to a conditional withdrawal of the popular initiative; this will take place once the indirect counter-proposal enters into force (probably 01.01.22).

The formula

Definition of relative market power. So what is the groundbreaking formula – to speak again in the jargon of the parallel drawn at the beginning – that is supposed to permanently change the Swiss world view of market power? The spectacular answer (at the most for those who are extraordinarily fond of antitrust law):

“The Cartel Act of 6 October 1995 is amended as follows:

Art. 4 para. 2bis

2bis An undertaking shall be deemed to have relative market power if another undertaking is dependent on it in relation to the supply of or demand for a good or service in such a way that there are insufficient or unreasonable opportunities to switch to another undertaking.

Abuse of relative market power. The elements of abuse are the same for companies with absolute and relative market dominance and arise from Art. 7 of the Act. This is supplemented by lit. g as follows – and this explicitly addresses the “high price island Switzerland”:

“1Dominant undertakings and undertakings with relative market power behave unlawfully if, by abusing their position on the market, they hinder other undertakings from commencing or exercising competition or disadvantage the market opponent.

2Such conduct shall include in particular:

g. the restriction of the possibility of demanders to obtain goods or services offered in Switzerland and abroad at the market prices there and the conditions customary in the industry there.”

First assessment. Some thoughts on these still young provisions of Art. 4 para. 2bis KG and Art. 7 para. 2 lit. g KG:

- The legislator’s formula is strongly based on Section 20 of the German competition act, which also contains the elements of sufficient and reasonable possibilities of switching to competitors. Accordingly, for the Swiss practice, a significant recourse to the case law developed in Germany is to be expected.

- The wording of the law incorporates the latest amendment to Section 20 of the German act: Just as now in Germany, not only small and medium-sized enterprises are protected. Relative market power can theoretically also exist in a constellation with big companies. It will be interesting to observe whether and how large companies will make use of the concept of relative market power.

- The practice of the Competition Commission on Art. 4 para. 2 of the last decades cannot be seamlessly transferred into a practice on Art. 4 para. 2bis. In our opinion, this is not at all advisable; rather, the WEKO should quickly and from the outset create an independent practice with actual leading cases on relative market power and increase legal certainty for companies.

- In addition to the Competition Commission, its appeal bodies – the Federal Administrative Court (Bundesverwaltungsgericht) and the Federal Supreme Court (Bundesgericht) – are also called upon: In the case of the concept of relative market power, which is open to interpretation, real clarity and legal certainty can only be created by decisions of the highest courts. It is therefore necessary for the courts to conduct the corresponding appeal proceedings quickly and in a well-founded manner.

- For cases under Art. 7 para. 2 lit. g, it will be interesting to observe whether the Competition Commission will take cases of cross-border price or condition discrimination on the basis if the company with market power does not have any assets in Switzerland. From the perspective of the lack of enforcement mechanisms in international economic law, such proceedings are not to be expected. If, however, there are subsidiaries with a Swiss domicile, the BMW case (Federal Court ruling 2C_63/2016 of 24 October 2017; the WEKO imposed a fine of approximately CHF 156 million on the Munich parent company of BMW, yet the case involved an agreement) shows that the Commission is certainly prepared to take rigorous action in the case of cross-border discrimination.

- Against this background, Swiss civil antitrust law – international enforcement is unproblematic in the area of civil law – also comes into focus: The new Art. 4 Para. 2bis has some potential to reveal the weaknesses of the Swiss legal system with regard to civil antitrust enforcement on the one hand, but also to provide a remedy for this on the other: Civil courts will certainly be in great demand in the future when assessing an abuse of relative market power. After an initial warm-up phase, these could increasingly gain certainty and contribute to more efficient (civil) antitrust enforcement. In any case, the introduction of relative market power as a catalyst for (so far almost non-existent in Switzerland) civil antitrust proceedings would be desirable.

Conclusion and outlook

After a long struggle, Switzerland has now also decided to introduce the relative market power concept as established in Germany. In doing so, parliament adopted a definition of relative market power that is strongly oriented towards the wording of the GWB. However, it remains the task of practice to define the prerequisites for the determination of relative market power.

“Ever since the mathematicians fell over the theory of relativity, I myself no longer understand it” (Albert Einstein, 1907/08). In this sense, dear WEKO, do better and let us understand “your” theory of relativity! For this, Einstein gives us another maxim: “You have to make things as simple as possible. But not simpler”… because we lawyers also want to have fun with it (= argue about who is right).

Prof. Dr. Patrick L. Krauskopf, LL.M. (Harvard) is a professor at the Zurich University of Applied Sciences (ZHAW) and partner/chairman of Agon Partners (Zurich/Pfäffikon). Dominic Schopf is a trainee lawyer at Agon Partners.