Conference Debriefing (23): IKK 2021

Top-class line-up, the Commissioner chatting in the Zoom chat, breaking up GAFAs: The 20th International Cartel Conference (IKK) of the Federal Cartel Office on 4 March 2021 stood out positively from the large crowd of virtual conferences. Philipp Offergeld reports.

The thought of just another virtual conference on current topics in competition law may bore some readers who may be willing to wave goodbye with thanks. In addition to the frequently repeated topics and statements with little innovation in the market for regulatory approaches, there are often technical problems. In contrast, the 20th International Competition Conference of the German Bundeskartellamt, the Federal Cartel Office, was convincing with panellists from all over the world, smooth technical proceedings and some exciting positioning.

Trooping colours

The first star-powered panel consisted of the host and President of the German Federal Cartel Office, Andreas Mundt, Executive Vice President Margrethe Vestager, the German Minister of Economics Peter Altmaier and Isabelle de Silva, President of the French Autorité de la Concurrence. The uncrowned queen of antitrust, Margrethe Vestager, used the last seconds before the opening of the conference to reposition the EU flag behind her, “so people will recognise me”. In order not to risk any confusion, Peter Altmaier was equipped with the German flag side by side to the EU flag – and a background with Ministry branding.

Economic = political power?

The opening session was entitled “Business or Government – Who is shaping our economy? Various current topics were discussed, including of course the Digital Markets Act (DMA). Here, Andreas Mundt emphasised that national agencies must also have a strong role in enforcing the DMA. In view of the dispute between Facebook and the Australian government, he asked whether Facebook and Google wield too much political power. Vestager expressed confidence that she would be able to finalise the DMA during the French Council Presidency in the first half of 2022.

On the round’s lead topic – the role of the state in the economy – the audience enjoyed the assurances that were to be expected: Of course the state would withdraw from state involvement again, there were extraordinary reasons for investments like those in Lufthansa and Curevec, the Commission had tirelessly enforced state aid law, and the state is not the better entrepreneur. The charming Franco-German presidential duet did not spare Altmaier the memory of the failed Siemens-Alstom deal and his industrial policy strategy that was not very welcome everywhere. Vestager took the opportunity to point out that the Alstom-Bombardier merger had worked out… Of course, China also made an appearance at this summit.

Break-ups after all?

Panel I revolved around the question of whether regulation of digital platforms is sufficient or whether structural remedies, in other words, breaking up digital gatekeepers, might not also be necessary. The panelists were Cristina Caffarra, economist at CRA and well-known critic of big tech (this time she did not have her samurai by her side, her legendary companion of frequent conference appearances), Andrea Coscelli, head of the Competition & Markets Authority in London, Monika Schnitzer, economist at Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich and one of the German “Wise Economists”, Rebecca Kelly Slaughter, Acting Chairwoman of the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC), and Philipp Steinberg, Head of Economic Policy at the German Ministry of Economics in Berlin. The round was moderated by D’Kart editor Rupprecht Podszun.

Cristina Caffarra stated that the reluctance of Europeans towards structural remedies in antitrust law was astonishing. Rebecca Slaughter of the FTC may be placed in the camp of those in favour of structural measures. This is implicit in the fact that the FTC (together with a large number of US states) has filed suit against Facebook for the purchase of WhatsApp and Instagram. She stressed that structural remedies are not, in the view of many Americans, a radical but rather a moderate-conservative response to anti-competitive behaviour. After all, she said, they are done with, once unbundling is done with – in contrast to behavioural remedies where government authorities engage in long-term monitoring of companies. Monika Schnitzer also expressed a positive view of break-ups: Just as merger control prevents monopolisation, unbundling can also strengthen competition. Monopolisation demonstrably leads to less pressure to perform. Schnitzer cited the quality of Google search results as an example – she sees a decline of quality in recent years. She therefore has no great concerns that innovation will be stifled if regulation is tightened or unbundling takes place. As far as data protection is concerned, she dismissed consent as a sufficient remedy: “consumers will always give their consent”.

An interventionist panel, in other words. Slaughter, who zoomed from home with refreshing vibes, reminded her colleagues from around the world that they were, after all, obliged to stand up for the common good and democracy. Caffarra framed this in a blithe rant against the theses in the current issue of the Economist: The model of competition of the big digital giants advocated there does not correspond to her idea of competition. Andrea Coscelli was a bit more restraint in words – and needs to deliver. Fittingly for #IKK2021, the CMA had initiated proceedings against Apple over the App Store.

Sleeping participants

Contrary to what the subtitle might suggest, none of the participants (recognisably) fell asleep during the panel, which would have been surprising given the exciting topics. Rod Sims, head of the Australian government agency ACCC, nevertheless took part in the conference while sleeping. The virtual conference took place in the middle of the night according to Australian local time. Sims had prepared a video message that was played instead of his personal participation. He predicted success for Australia’s new media law (which, incidentally, is also the subject of this week’s “Bei Anruf Wettbewerb” podcast). Remarkably, he said that GAFAs share price would halve if its revenues did not continue to rise.

Fact check in the chat

With regard to European law, Philipp Steinberg spoke in favour of enabling structural measures in the DMA. This is remarkable in that the German negotiators from the Ministry of Economics are thus positioning themselves (albeit cautiously) in favour of strengthening such measures. And Germany may not be alone in this, as Steinberg has a new circle of friends, the “Friends of an Effective DMA Group”, which he says includes France, Belgium and the Netherlands as well as Germany. So the camp for the trilogue negotiations seems to be sorting itself out.

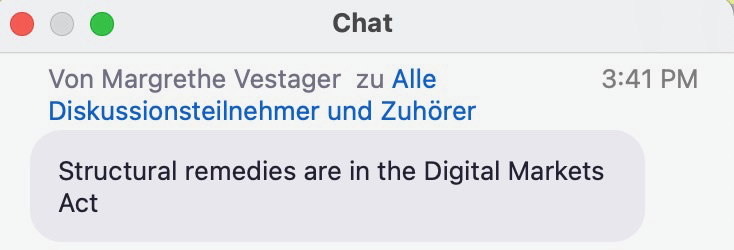

For a short time in the discussion it looked as if structural measures were not even foreseen in the DMA – but fortunately someone was around who knew better: Commissioner Vestager was apparently still interested in the conference after her own discussion slot – and had paid attention: She immediately typed into the Zoom chat window and pointed out that such measures were already provided for in the draft DMA.

That is true, see Article 16 of the draft DMA. However, it is also true that the scope of application for such measures is so narrow that it is likely to be a theoretical option, at least for the time being.

Philipp Steinberg, after highlighting the good work of the Commission, stressed the importance of national competition authorities for effective enforcement of antitrust law. Host Mundt will have been pleased to hear it. In any case, Steinberg’s line had strong echoes of the German way in Section 19a GWB, for example, he expressed doubts about the “self-executing” prohibitions in the DMA. Such bans, too, would ultimately have to be controlled by an authority. Schnitzer also doubted that this could work with the planned staffing plan.

Public policy goals?

Panel II dealt with the tension between antitrust law and other environmental and social aspects in the public interest. The discussion was moderated by Ingo Brinker, lawyer and chairman of the Studienvereinigung Kartellrecht, the group of German competition lawyers. Participants were Tembinkosi Bonakele, Head of the South African Competition Authority, Olivier Guersent, Director-General for Competition at the European Commission, Alejandra Palacios Prieto, Chair of the Mexican Competition Authority, Martijn Snoep, Chair of the Dutch Competition Authority, and Achim Wambach, economist and member of the Monopolies Commission.

The first speaker was Tembinkosi Bonakele, who gave a historical insight into the origins of South African competition law, where general interests – especially the fight against the consequences of apartheid – have always been pursued. Competition law has always been understood there as a general regulatory framework of the economy.

In the further discussion, the subject matter then focused in particular on environmental protection as a general interest – as had already been the case at the Bundeskartellamt’s Professors’ Conference (which we reported on here). Martijn Snoep, whose Dutch competition authority ACM has caused quite a stir with a draft guideline on sustainability initiatives, pointed out that European antitrust legislation is not an end in itself, but only an instrument to realise one of the Union’s goals, namely the free internal market. Thus, antitrust law does not claim priority over other Union objectives, including environmental protection, Snoep contended. Olivier Guersent also described antitrust law as an instrument for the realisation of the internal market. From his point of view, the protection of competition may nevertheless have a certain special position, as it is of outstanding importance for the European economic constitution.

European Monopolies Commission?

Achim Wambach pointed out that efficiency advantages resulting from the reduction of emissions are difficult to quantify. It is always important, he said, to check whether the emissions are not just generated by another company.

From an institutional point of view, he considers the establishment of an independent European advisory body necessary to support the Commission in the application of the law, especially in economic issues. He dreams of modelling this according to the status of the Monopolies Commission for the Bundeskartellamt.

In the first panel, Steinberg, the policymaker, who has not been living in the “antitrust bubble” for ever, had spoken of an opening up of the antitrust world and noted the breaking up of the monopoly of interpretation, so far held by competition experts. This is a double-edged sword, though. It was helpful to have the example of Mexican antitrust chief Palacios Prieto in the digital room: She is in conflict with the state president over renewable energies, and this conflict pretty much has all dimensions of independence of authorities, politicisation and pure concepts of competition law.

Conclusion

The 20th edition of the IKK was a treat for bringing a first-class and varied line-up to your home. At times, up to 1,000 participants from all over the world were present. In his closing remarks, Andreas Mundt promised a face-to-face event in Berlin next year. Will there already be a DMA, the first GAFA break up and a revived pure market economy after the pandemic? Mundt’s very own optimism is here to stay.

Philipp Offergeld is a researcher at the Chair for Civil Law, German and European Competition Law at Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf and a doctoral student with Prof. Dr Rupprecht Podszun.

One thought on “Conference Debriefing (23): IKK 2021”