Conference Debriefing (28): “Data Access for Service Providers”

Who has access to data? This has become a key question of the digital economy, which increasingly concerns industry and trade. There is a danger that individual data monopolists will decide on access to customers and opportunities in competition. Rupprecht Podszun’s team has taken a close look at the issue and – together with the Ministries of Justice and Economic Affairs of Northrhine-Westphalia – invited participants to an online workshop. Clemens Pfeifer reports.

For the recording of the entire event (in German), click here: YouTube

Name of the event:

Data Access for Service Providers | Law – Practice – Perspectives

Topic:

How must access to data, software and platforms be designed in the smart world to ensure competition and innovation?

Place & time:

2.2.2022 via Webex (it even worked!)

Hosts:

A trio: Our very own Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf (namely our chair) had allied with the NRW Ministry of Economics (correct abbreviation: MWIDE) and the NRW Ministry of Justice. NRW stands for Northrhine-Westphalia, the Land with the most inhabitants in Germany. The ministers Prof. Dr. Andreas Pinkwart (an economist, actually specialized in innovation management) and Peter Biesenbach (a lawyer) welcomed the participants.

Audience:

Almost 170 interested people, who also participated in lively discussions from their homes and asked investigative questions. Among them were antitrust lawyers like Eberhard Temme from the Federal Cartel Office, numerous lawyers with well-known names in the German bubble, academics like Axel Metzger and Simonetta Vezzoso, many people from associations, chambers and companies. (And of course the one guy who directly enriched the chat with his LinkedIn profile without being asked).

What a strong setting!

Prof. Dr Andreas Pinkwart Peter Biesenbach – a high profile welcome

Indeed, the list is long. The panels were attended by top-class people from practice, academia and politics, so it was worth logging in. Besides, it is not every day that a minister is scheduled to give a welcome address but then stays for the whole day. Apparently, Minister Biesenbach found the topic so exciting that he decided to follow it. In his house, the unit for digital legal issues (headed by Eva Lux) had taken the lead – the team had already proven itself in the Working Group “Digital New Start” of the state ministries of justice in Germany – their reports are a treasure trove for all those who want to plough digital legal issues, as the students of Prof. Podszun were already able to experience in their seminar papers… In the North Rhine-Westphalian Ministry of Economics, the unit for competition law was responsible (Head: Christopher Harrell). Jennifer Gerwing, an MWIDE officer, led the day with aplomb.

Why all the fuss?

The Ludwig Fröhler Institute for Craft Sciences had commissioned Rupprecht Podszun to conduct a study on the crafts sector in the digital economy (open access). Well, craft is the translation for “Handwerk” which seems to be a very German thing – just translate it to service providers like the plumber, the car mechanic or the chimney sweeper. The findings are worrying for those who care about free competition and independent SMEs. There is a threat of not too distant future scenarios like that of Mr K:

It is 12 October 2025. Mr K’s smart heating control system detects irregularities in the recorded data that indicate a defect is imminent. Mr K is threatened by a cold winter, but the data system operated by the heating manufacturer sounds the alarm directly on the manufacturer’s own platform – and activates a suitable service provider who can carry out the maintenance. The service provider already has the necessary spare parts, of course from the manufacturer’s production. And pays the manufacturer a hefty commission for the job. This is really practical for Mr K!

Even if Mr. K would rather hire his proven and also simply much nicer craftswoman H instead, he would not have the chance to do so: Firstly, he does not even find out that the standstill of his heating is imminent. And secondly, H would have to be connected to the manufacturer’s platform. If she is not, because the commissions are too high for her, she cannot access the log data of the heating system and therefore cannot help Mr K in a targeted way.

However, he cannot give it the data he has generated himself with his own heating system – only the manufacturer has access.

Hmm. What then becomes of the SMEs?

In the digital economy, things could look bad for service providers. Without viable access to platforms, interfaces and data, they could become mere fulfilers, taking orders from those who control the data boxes. This could be the manufacturers, but also data platforms like Alphabet or the organisers of a smart factory. With an average size of five employees, a normal Handwerk-business can hardly stand up to this on its own. The more smart products come onto the market, the further networking advances, the more important the question of who controls access becomes. Customers will lose their role as “referees” in the selection of the best providers, which is so important for competition, because not everyone will be able to offer what they want. Start-ups that want to develop innovative business models based on new data sets are also dependent on access.

Until now, access to data has been dominated by de facto control, regardless of who actually produces the data (as with Mr K’s heating system). Podszun said in the opening discussion with Eva Lux: “At the moment, it’s a pure “might is right” power system – the powerful prevail. That is not a our idea of the law.”

Surely that can be solved. After all, there were some smart lawyers on the panels.

Watch out, no bragging of our great legal supremacy, please, some panellists felt they had to apologise for not being lawyers, although the reports from business practice were particularly exciting.

There are a number of instruments for fair access, but the question of which one would be the most effective turned out to be particularly controversial. Lawyers may be inclined to simply grant a substantive right. That may work. Trade representative Alexander Barthel of the ZDH, the Handwerk-body, for example, praises the good solution of the Metering Point Act, which allows electricity customers to freely choose an electricity meter. However, pure legal claims bear the risk of not being quite as effective in practice as they are on paper. If the parties opt for confrontation, they can easily end up arguing for years through the courts and in the end the subject matter of the dispute is long outdated. This is of no help to anyone. Gerhard Klumpe, presiding judge at the Dortmund Regional Court, also confirmed that he was not aware of any proceedings under the new data access rules in the German competition act that had been introduced in 2021. Section 19 (2) No. 4 and Section 20 (1a) give far-reaching data access rights. However, litigation is probably too costly, too lengthy.

Entrepreneurs are also not fans of pure legal rights. They could perhaps be too comprehensive and then inhibit incentives for innovation, warned Stanimira Markova of construction start-up Greenbimlabs. She had to invest years of research to turn data processing into an innovative business model. The claim could also be too general, seconds Christian Els from AI company Sentin. In that case, a claim would not do justice to the individual needs of different applications and would also come to nothing. One would have to know relatively precisely in which constellations who needs which data and should also receive it. But where exactly are these areas of application, asked Rebekka Weiß from the German IT-lobby association Bitkom. And do we want to regulate them all individually?

The whole thing sounds like a cat-and-mouse game of new business ideas and the laws to make them possible. But at the speed of the legislature, one suspects how this will probably turn out. There must be another way.

Wouldn’t it be easiest if everyone sat down at the table and found a solution?

That would be the best thing, of course. And that’s probably how it works, for example with lift maintenance, said Philipp Voet Van Vormizeele, a well-known antitrust lawyer by training, who is now a board member at TK-Elevator. Lifts today already produce a lot of relevant data. The (quite lucrative) maintenance of the lifts is sometimes done by a competitor of the manufacturer. The data required for this is provided – “that is an essential facility”, PVVV knows. It seems that in the lift business no one is, well, stuck.

The EU is developing a data infrastructure for Europe for this purpose with its Gaia-X project, with which data can be exchanged simply and securely and, above all, also ported and used with other data. Gerd Hoppe, who is involved in the project with the automation company Beckhoff, is convinced of this interoperability solution. Gaia-X still sounds somewhat abstract and theoretical, but the idea has an enormous appeal.

Then all is well?

All this still stands and falls with the voluntariness of those involved. And that cannot be taken for granted. If everyone joins in, that is of course no problem. “The parties concerned must really be able to negotiate at eye level,” explained DICE economist Justus Haucap. That may be the case in the elevator industry, but different conditions prevail in many markets. Where platform economies, network effects and the large concentrations of power in GAFA+ (MAMAA or whatever you want to call it) show us how quickly a market can tip.

And even if an amicable solution is to be found, the partners still encounter enough pitfalls. Lawyer Henriette Picot described the ambiguities that still arise in data sharing and licensing agreements: The type of contract is open. To be on the safe side, one would have to regulate all consequences of defects and liability cases in detail. Those who do not do this end up playing roulette as to which rules apply. An extra contract type that addresses the interests of the data economy could perhaps help here. In German law, this could then be another paragraph of the holy Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch (BGB) with a k at the end.

Was there ever a real fight on a panel?

Oh yes! When it came to cars, of course. The example is nice because, on the one hand, sector-specific rules on data exchange already apply in the automotive sector and, at the same time, the distribution battle is in full swing – Politico recently wrote that the “Next Monopoly Game” is coming up in the industry. Joachim Göthel, representing the manufacturer association VDA had to face Marcus Büttner, who is a representative of the traders and workshops in the car industry. His colleagues are sometimes in despair of the manufacturers’ barriers. All set for a good discussion!

For the workshops, access to the data in the vehicle is absolutely essential: they need it for repairs, for the installation of a parking heater, for the official auditing test. Without access to the data box, their business simply doesn’t work.

But the manufacturers are not really keen on sharing data. Independent garages that are not tied to a selective distribution system still can’t get everything they need. According to Büttner, it is simply not feasible for some workshops to join all the systems, given the costs involved.

Economist Wolfgang Kerber was on that panel, too, right?

Exactly. The economist from the University of Marburg has been dealing with the plans of the car manufacturers for “connected cars” for a while now. In the meantime, data & cars is no longer just about repair and maintenance information, but about comprehensive communication of the car with everything. Kerber is not exactly enthusiastic about the car manufacturers’ plans. In his view, they are causing “a whole host of problems” with their handling of data from connected cars. After all, if they have their way, all the data produced will be sent exclusively to the manufacturers’ servers, and they will retain de facto control over access. And with complete control over the data, the manufacturers also control all the secondary markets associated with it. They become gatekeepers.

Oh, that’s a bad word in the competition scene now, when I think of the DMA….

We will come to European law in a moment, but another point is of course still unclear: Why should the manufacturers, of all people, profit particularly from the data that the users, the owners, who have bought the cars for a lot of money, produce with their own behaviour? “My car, my behaviour, my data”, that’s how it could be calculated for a start. And incidentally, many stakeholders want to access this data, not only car repair shops, but also insurance companies, mobility providers and the public sector.

What does the VDA representative think about Kerber’s gatekeeper diagnosis?

Mr Göthel “was not amused”, I say. He emphasised the trustworthiness and security of the data for the model preferred by the manufacturers. Against the background of the emissions scandal, the argument of “trustworthy data” by car manufacturers was accepted by the audience partly with a wink. But well, of course it is also about profit interests and, it must be fairly emphasised, about investment incentives.

But now to European law, what is happening there?

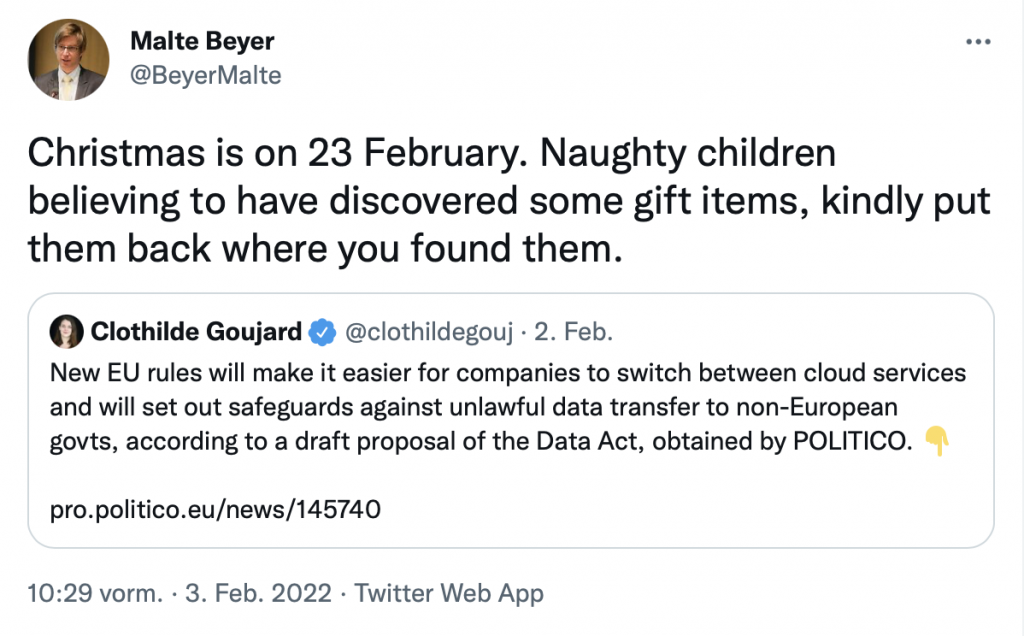

The EU Data Act is just around the corner! Is this perhaps the salvation? Malte Beyer-Katzenberger from the European Commission is of course convinced, unfortunately without going into too much detail, what exactly awaits us on 23 February 2022 when the Commission’s proposal for the Data Act is due to be presented – the first leaks have already occurred, by the way, but Beyer-Katzenberger asked in a very funny tweet that we should please, like good children who discover their Christmas presents prematurely, put them back and not let on.

In any case, there will be several ways to improve access to data. Among other things, the Data Act is to be based on the user’s right of portability. That sounds good at first, but it also reminds me of the great portability right from Article 20 of the GDPR. Don’t you know it? Exactly.

But the problems were probably seen, says Beyer-Katzenberger. If the portability right is technically well implemented and automatically available in real time, then it can work. The PSD-2 directive with the mandatory open interface for payment services demonstrates this.

What next?

Most agree that access must be created. The Data Act proposal will structure the discussion, but the search for the best means to achieve this remains a difficult project. Now it’s up to regulators and market participants to start from different angles, to try out different things and, above all, to continue exchanging ideas on whether the bold ideas of theory also live up to reality. The experimental sandboxes, set up by the NRW MWIDE Ministry, could now provide insights – i.e. legal experiments in the real-live world. Many people find this creepy, but we remain curious to see how it turns out!

For the recording of the entire event, click here: YouTube

Clemens Pfeifer is a researcher at the Chair of Civil Law, German and European Competition Law and a doctoral student with professor Podszun at Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf. He contributed to the aforementioned study “Handwerk in der Digitalisierung – Zugang zu Daten, Software und Plattformen”.

If you would like to be informed about new postings by e-mail: To the newsletter subscription!

One thought on “Conference Debriefing (28): “Data Access for Service Providers””