SSNIPpets (45): Fringe

In the traditional summer slump, there is some time to explore the fringes of antitrust law. The grass is always greener on the other side, so Rupprecht Podszun took off his blinkers for once and feasted his eyes on the little flowers left and right. Here are his SSNIPpets – small but significant news, information and pleasantries – our pet project!

Antitrust is dead

Fewer and fewer professors are doing antitrust law, at least in the US. In an article for promarket.org, Dan Crane observed that in the past five years, out of 417 new law professors in the USA, only 7 listed “antitrust” as one of a maximum of four areas of interest. “Antitrust is dead, isn’t it?”, Crane quotes the well-known colleague Richard Posner. In 2017, Posner had claimed that.

As we all know, the dead live a little longer, and especially in the USA one does not have the impression that antitrust law is dying. Posner also says in the same interview that Microsoft, Amazon and Google are the three best companies in the world and that he doesn’t see where there is a problem. Hm, hm. Lina Khan may disagree. “I spend a lot of time googling, so I don’t want to hear criticism of Google,” Posner says later, when his interviewer Luigi Zingales tells him about Google’s practices. Oh, Posner is allowed to do that, he is 82 years old today and a living legend.

Lina Khan has the makings of a legend. She is fifty years younger and now head of the Federal Trade Commission in the USA. At the age of 32! In Germany, at 32, if things go very well, you are a Oberregierungsrätin at the Federal Cartel Office. Which might not be so bad either. Now: Deliver.

Assuming Posner was right and antitrust was dead – what would we actually do then? Other nice things are on the fringes. Let’s have a look!

Fines for unfair commercial practices?

It is a revolution in unfair competition law, and it is a small defeat for the Bundeskartellamt: on one of the last days when the Bundestag was still productive this year [there is an election looming], on 10 June 2021 at 11.53 p.m., Parliament started the second and third reading of the Act to Strengthen Consumer Protection in Competition and Trade Law as agenda item 30 in its 233rd session. The speeches – except for one – were put on record, i.e. submitted in writing, as one does when eight more agenda items are pending shortly before midnight and the session is not closed until the Substitute Building Materials Ordinance has also been discussed. Wolfgang Kubicki, as Vice-President of the Bundestag, moderated these changes in unfair competition law with the speaking pace of a German notary (which is equivalent to Lamont Marcell Jacobs running).

The Unfair Competition Act (UWG in German, the German implementation of the UCP-directive) is being reformed in a revolutionary way – naturally under pressure from the EU. In future, in the case of violations of the UWG, there will be – firstly – an individual claim for damages by consumers (§ 9 (2) UWG). Previously, consumers did not have this right, because, as was emphasised mantra-like, the UWG only protects the collective interests of consumers, while individual damages were to be claimed according to the German Civil Code (BGB). Secondly, there is now a possibility to fine companies in § 19 UWG! Up to now, only cold calling was subject to a fine in Germany (§ 20 UWG). Now all kinds of consumer law violations can be fined, as far as they are – attention – “widespread” in the sense of the CPC Regulation. The CPC Regulation is a European legal act on cooperation between national authorities to ensure consumer protection.

Not really…

So now fines? Well. In the explanatory memorandum of the Federal Ministry of Justice and *for* Consumer Protection, one can almost read how grudgingly the requirements from the Brussels legislative machine are being implemented. It is not too bold a prognosis that successful consumer damage claims and fines for misleading advertising will not immediately reach antitrust dimensions. (Well, with regard to individual claims for damages, antitrust law is of course no benchmark either). At least the law on fines is predefined by antitrust law, e.g. with an upper limit based on the percentage of the company’s turnover.

Which authority then imposes these fines in Germany as of now? This brings us to the Bundeskartellamt’s small defeat. People like yours truly have been arguing for a long time that the Federal Cartel Office should also be entrusted with the powers necessary to protect fair competition (see above all our expert report for the Federal Ministry of Economics). The Federal Network Agency, which is after all responsible for fines for cold calling under § 20 UWG, also had ambitions. However, the Federal Office of Justice (Bundesamt der Justiz) in Bonn has now been awarded the competence – an authority that has so far not been particularly conspicuous either in the field of commercial law or through its investigative experience. It is probably part of the grudge not to involve the Bundeskartellamt’s bustling Decision Division V. § 19 UWG will be a lame duck. Why? Please read that in my commentary on it in “Harte Henning” (which is a wonderful German commentary on this law #ad).

Grotesque defensive performance

In any case, it is grotesque how attempts are being made not to create effective public enforcement to protect fair competition. By the way, Germany is pretty much alone in its reliance on private enforcement by consumer and business associations. It goes without saying that the Wettbewerbszentrale, the consumer association VZBV and others are doing awesome work with private enforcement in this field. But their warnings and injunctions have their limits: private parties can hardly investigate, they have little incentive to plunge into uncertain proceedings, civil law decisions only work between the parties, and the infringers usually keep their law-breaking profits.

Let’s be clear about this: I am not at all a fan of a rampantly applied UWG that sanctions every little thing. Unfair trading law lacks a “more economic approach”. But economic also means that effective action must be taken against the big messes. This would require public enforcement of the law, as we are used to from the Federal Cartel Office: Powerful, but also with a sense of proportion. I’ll put this on my wish list for the coalition negotiations at the federal level due after September 26.

An end at last

The Palandt is now called Grüneberg, the Schönfelder Habersack. The eternally right-wing Theodor Maunz no longer lends his name to a leading commentary on the German constitution. Walter Blümich’s name is removed from a commentary on tax law. We are talking here about a step undertaken by publishing house C.H. Beck that was long overdue: The names of former Nazis like Palandt that were still on very successful standard law books are to be deleted. Palandt Grüneberg, for instance, is the undisputed German No. 1 book on the civil code. It is hard to understand that up to now it had the name of Palandt, thereby commemorating a strong ideologist of national-socialist law. This comes more than 30 years after Ingo Müller’s breathtaking work “Furchtbare Juristen” [Terrible Lawyers] where Müller had chronicled the careers of Nazis in Western Germany. Since 2017, the initiative “Palandt umbenennen” [Rename Palandt] had been putting pressure on the publisher. I am ashamed how long we put up with this. After all, as early as 1964, the upright liberal politician Hildegard Hamm-Brücher had been able to bring down Theodor Maunz as Bavarian Minister of Culture because of his Nazi past.

This does not mean that we are now done with looking into the history of our trade. As antitrust lawyers, of course, we are somehow off the hook – our field of law is already anti-totalitarian to begin with, it has only really existed since the 1950s in Germany, and Franz Böhm and Walter Eucken, the intellectual godfathers of German competition law, have – according to their Wikipedia entries – a clean slate. There is no indication that a standard book on antitrust has to be renamed.

In Unfair Competition Law, things are different, as I once explained here. Wolfgang Hefermehl, who had a formative influence on the UWG for decades, was a senior court judge in Frankfurt am Main from 1941 to 1945 and a member of the SS, a particularly gruesome Nazi organisation. In 1938, he wrote an essay on “Die Entjudung der deutschen Wirtschaft” [The de-Jewification of the German economy], which appeared in “Deutsche Justiz”. In 2015, the University of Salzburg posthumously withdrew an honorary doctorate awarded to him in 1983. His famous book on unfair competition law is no longer named after him, but it still appears, now under different names, in an unbroken tradition, and Hefermehl is still mentioned on the cover page. As far as I can see, this book on the UWG has been published since 1929, initially by the publishing house of the Jewish publisher Otto Liebmann, who sold out to Beck in 1933.

When I write it down like this, it is not about exchanging names (Hefermehl still adorns the cover of a commentary on the law of payments) or about breaking the baton on decisions that my generation never had to face. But that our guild of lawyers is still quite blind to the perversions of law, that is dishonourable. As usual, I am happy to read your comments on this, but in this matter in particular, I am happy if you share your knowledge.

On the privatisation of the most private

I have always been fascinated by the business idea of the Sanifair vouchers from Tank & Rast as a brilliant rip-off model: a toilet at the motorway is made chargeable. This may not be necessary, it may even be indecent, but it is permitted, as the Rhineland-Palatinate Higher Administrative Court (OVG) ruled. In the original concession agreement of undertaking Tank & Rast with the Federal Republic of Germany, it was promised that efforts would be made to ensure free use of bathrooms… – but, well, that was a promise of good effort, as State Secretary Enak Ferlemann explained in 2012 with a shrug of his shoulders in response to a question from Anton Hofreiter in the Bundestag (BT-Drucks. 17/10460, p. 119). So much for the executive’s skill in negotiating privatisation.

Instead of simply taking 20 cents from the pinchers, they are given a voucher for 50 cents in return, which can be redeemed in the petrol station shop – where, of course, 50 cents buys next to nothing. As a result, the German money-saver is faced with an almost insoluble dilemma: does he let the voucher he has just won expire and flush 70 cents down the toilet with it? Or does he redeem it and buy something overpriced in the shop? According to surveys, Germany is torn on this question. Winner: Tank & Rast. They own the toilets, the shops and the petrol stations. Almost everywhere along the Autobahn.

I can hear German readers snorting. Podszun, we’ve known all that for a long time. With content like this, D’Kart will soon be a worn-out toilet reading like the ancient editions of Tintin next to the loo! Yes, yes, all right. At least there is a bit of news: Victor Perli, a member of the Left Party, has taken up the issue again in a question to the federal government (BT-Drucks. 19/30037). In it he quotes with relish from a Moody’s rating according to which Tank & Rast is stably dominant. The Federal Cartel Office has also provided ammunition with the Market Transparency Unit for Fuels: According to this, the prices at Autobahn filling stations for fuel are about 20-25 cents above the usual prices – and also considerably higher than those of Autohöfe, petrol stations that are a minute away from the Autobahn. We know all that. But maybe it doesn’t have to be that way. Just because people have become accustomed to exploitative practices does not mean that they are permissible.

Cleaning mania in the cartel office

Since we are on the subject of hygienic conditions. In the future, the Federal Cartel Office will clean the desks. No, no, this does not mean that the case handlers have to disinfect the tables themselves at the meetings that are now taking place in presence again if a greasy cartel brother (they are usually all male, as we learned from colleagues) has been sitting at them.

When we talk about “self-cleaning”, we are of course talking about the Wettbewerbsregister, the competition registry. It is virtually ready to go, a team led by Kai Hooghoff is tinkering with the final details at the Bundeskartellamt.

When the Registry is up and running, it can be quite a game-changer for some companies: If you’re in, you’re out. (Nice formula, actually! ) Companies that are listed due to an inglorious past (e.g. because they were involved in a cartel) are blocked from public contracts. For industries that live off such contracts, this can become significant. The remedy is self-cleaning (not sure, this is the right word in English, though). The German Federal Cartel Office had put forward guidelines on what this could look like for discussion until 20.7.2021.

Unsupplychain my heart

In future, violations of the so-called Supply Chain Act can also be registered in the Wettbewerbsregister. The Bundestag passed a law shortly before the end of its legislative period on due diligence in the supply chain. I had dealt with it because we had Franziska Humbert from Oxfam as a guest in our lecture series on commercial law, and she presented the German Supply Chain Act from an NGO perspective. She quoted an expert on the Berlin bubble who said that it is “the most heavily lobbied law” ever. Maybe, maybe not, but the number of amendments introduced even at the last minute is astonishing. The alliances were all over the place: Conservative minister Gerd Müller forged an alliance with social democrat Hubertus Heil, whose advances were rebuffed by the conservative-led Federal Ministry of Economics.

Legally, the Supply Chain Act is fascinating, especially for those who deal with modern regulatory policy. For an antitrust lawyer, the basic idea can be quickly understood: We don’t want products to enter the market when they are infected by a cartel – no matter where that cartel was instigated. And now many people also do not want products to be traded when in the process, human rights were infringed – no matter where. I suppose that’s not controversial for now. (If you think cartels or human rights abuses are okay, please unfollow this blog).

The how

The controversy probably starts more with the how. Should companies active in Germany, e.g. the retail chains, be held responsible for what happens in the supply chain? Questions of attribution have always been one of the delicacies of the civil lawyer. For me, it is first logical that I cannot reap the benefits of the division of labour without also assuming the risks. If these risks are so cleverly externalised that I end up profiting from unpunished child labour, then something is amiss in terms of regulation.

The non-prosecution of child labour in State X is due to an enforcement deficit in State X (and not to other substantive standards – human rights are a universal standard). Is it now permissible to bring in a distant jurisdiction, say ours, to address this enforcement deficit in X? In antitrust law, we do this with the help of the effects principle, which I have always seen as a necessary legal equivalent to business globalisation. At the same time, we have also seen in antitrust law that with the help of an excessively interpreted effects doctrine, cross-border usurpations are possible.

If one is prepared to assign responsibility to a company in this country, the question arises as to how to do this in concrete legal terms. The German legislator has responded with a rich kit that mirrors some of what we know in antitrust law. It is a “regulatory mix” of the highest order: there are compliance regulations, documentation and reporting obligations. There are fines (up to 2% of company turnover). There is tort liability, which can be implemented through litigation by non-governmental organisations. It remains to be seen whether, and if so, which of the many mechanisms will ultimately lead to success.

An educated guess: The fines are not at first. They are to be imposed by BAFA, the Federal Office of Economics and Export Control, overseen by the more hesitant Federal Ministry of Economics. It is the small adjusting screws that will decide how strong the Supply Chain Act will be.

Patent party

What I can only touch on now: Patent law is being changed. You can’t think of patents without their flip side, free access to knowledge and thus free competition. In any case, I kept thinking about questions of the market and competition when I followed the debate about the suspension of intellectual property rights on vaccines or the stories about the settlement of the patent dispute between Nokia and Daimler.

Hats on

For us competition lawyers, the primacy of European law is an old hat, without which we do not go out the door. Some German constitutional judges prefer to go bareheaded. I don’t want to push the linguistic image too far, but the European Commission, putting on its hat as the guardian of the Treaties, has sent a “letter of formal notice” to Germany to remind it of that old hat. With it, the Federal Constitutional Court (Bundesverfassungsgericht) is told it was beanie-th (sorry for that one) its usual quality. The whole affair had started with the Second Senate of the German Constitutional Court located in Homburg Karlsruhe, stating in 2020 that the European Court of Justice had spoken ultra vires in the Heinrich Weis case, related to the European Central Bank. The Commission tries to cap that since it is worried that other courts in the EU will follow the example of the renowned German institution, calling in question the status of the ECJ.

Peter Meier-Beck, hat head of the Cartel Senate at the Federal Supreme Court (Bundesgerichtshof), a neighbouring top court, criticised the view of the constitutional judges very early on in this blog. He was one of the first prominent critics. You heard it here, first! It’s a feather in his cap, or as I would say: Chapeau!

Next level compliance

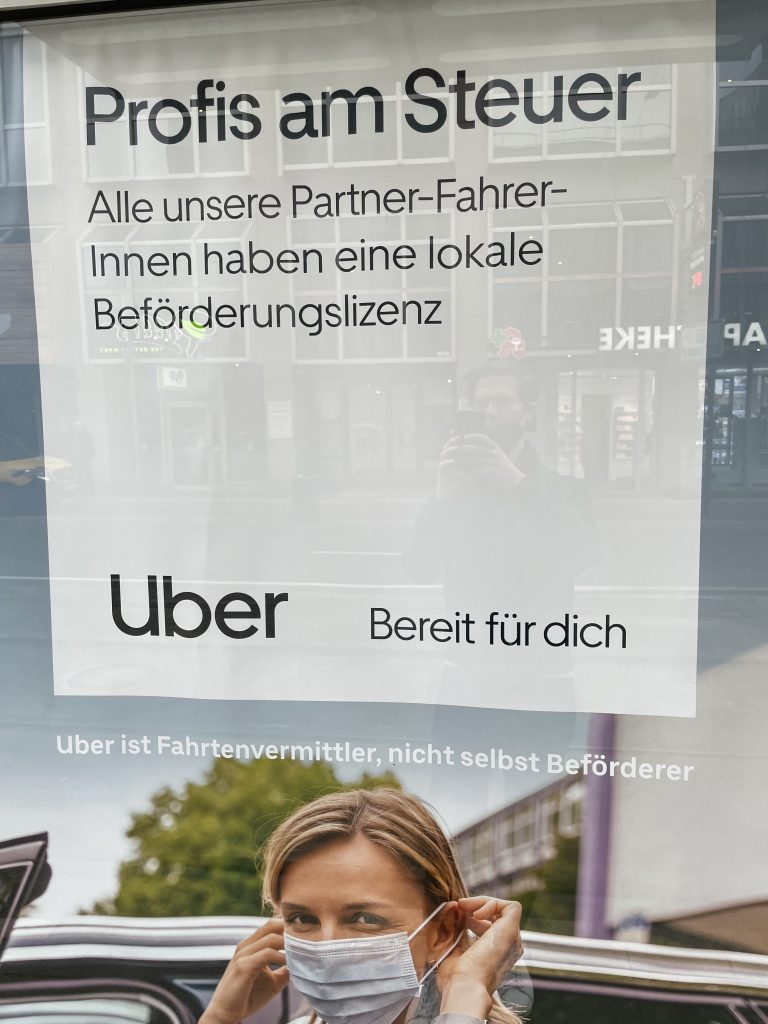

We started with unfair commercial practices, and so let me end there: The beautiful § 3a UWG, “Vorsprung durch Rechtsbruch”, still exists: If there is a breach of law, you may try to use private enforcement under unfair competition law to get a quick injunction, e.g. as a competitor – even if that infringement of the law is in completely other fields where usually public enforcement would tak place. Since public enforcement often takes a while, the option to run the case via § 3a UWG is a great choice. UBER can tell you a thing or two about it: The violations of the Passenger Transportation Act in Germany repeatedly slowed down the company here, and enforcement was partly carried out with the help of the UWG.

Now, UBER advertises that they are legally compliant in a big campaign in Germany: “All our partner drivers have a local transport licence”. I find this so touching. I’m curious, however, when other companies will start advertising that they observe German law. Facebook, Google, Amazon, Apple? Anyone? Observe the law and talk about it. Is this still advertising with self-evident facts – or is it next level compliance?

Please head into the weekend now! – Yours Rupprecht Podszun

PS: We have “suspended” our Facebook account. You should try that too. It didn’t hurt at all. Of course, you don’t have to do without Facebook – we have a big Facebook page here on the blog where we constantly post information on the most exciting German antitrust case in years.