In court: Pharmacy customer magazines

PDF-Version: Click here

Suggested Citation: Podszun, DKartJ 2023, 107-112

It’s about elderly ladies, an arrow diagram and has somethig to do with media: the German Bundeskartellamt defended a merger clearance decision before the Düsseldorf Higher Regional Court – a competitor would have preferred a prohibition. Rupprecht Podszun was at the oral hearing of the 1st Cartel Senate and reports.

Wednesday mornings at the OLG

When lawyer Till Steinvorth is given the floor, it is 11:27 a.m. on Wednesday, 15 November 2023, it is clear that he could pack his stuff and leave. It had taken presiding Judge Jürgen Breiler exactly 17 minutes to summarise the facts and the legal situation of the case to be heard from the perspective of the 1st Cartel Senate. There doesn’t seem to be much to negotiate from the senate’s point of view. Judge Breiler – he is the successor to the legendary Jürgen Kühnen – had made it clear in his opening statement that the plaintiff’s request would not be granted. And then he also warned all lawyers that they may confine themselves to comments that are not in the written pleadings.

That is of course a killer argument: it is hard to believe that there are still things that have not yet been addressed in writing in these proceedings. But Steinvorth (who has been missing in Düsseldorf since he moved to Hamburg in 2020) would of course not be a lawyer if he allowed himself to be intimidated by such remarks. With composure, he therefore once again makes the points that he probably considers essential. When he makes a correction to the statement of facts, Judge Breiler interrupts him: “It’s in the preparatory vote, but I have to present a condensed version here.”

The Chairman

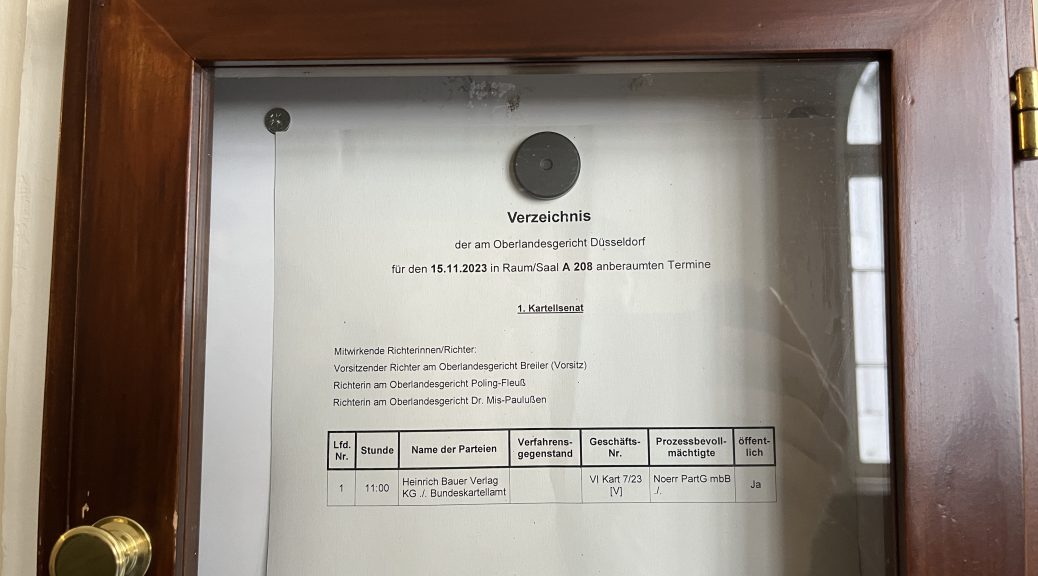

The prep vote relates to case VI Kart 7/23 [V] – Heinrich Bauer Verlag KG v. Bundeskartellamt. After less than an hour, the “condensed version” of this exciting media competition case is over, just as if the 1st Cartel Senate still had to rush through several other hearings in order to somehow manage the day’s workload.

Presiding Judge Breiler has Judges Alexandra Poling-Fleuß and Ursula Mis-Paulußen at his side. This is the first time I’ve seen him on the bench; he’s a tall man, commanding respect. Very serious, reading glasses. It is impossible to tell from his facial expression what he thinks of what is being said. He can, as he makes clear right at the beginning, be a little peeved: Anyone who wants to appear before this Senate should please have told us in advance who is representing the parties. However, not all party representatives have done so. So names and their spelling still have to be painstakingly noted down in the minutes. Breiler disapproves of this negligence.

Some backs of heads

These names belong to the numerous respectably coiffed backs of heads with black robes or at least dark clothing that I can see from the stalls. If you look up towards the judges’ table, you might overlook the fact that room A208 of the Düsseldorf Higher Regional Court is packed: the thick rain coats and large suitcases are cramped in the corners of the wood-panelled room, and the spectator benches are also quite packed, mainly with young people from the participating institutions and my competition law class. The only eye-catcher in the room is the large blue and white labelled glass bottle of mineral water that lawyer Donata Beck has confidently placed on the table in front of her. Beck, together with Ulrich Klumpp and Annika Witte Paz, is there for the parties to the merger that is being called into question today.

The case

If one were to conclude from the dark clothing that something is being laid to rest here, that would be a false conclusion, on the contrary: the birth of an advertising marketing machine is being approved here. Funke Mediengruppe is participating in a joint venture with Burda Verlag, BCN is the name of the baby. Both are important German publishing groups, still very active in print journals. BCN has so far marketed the so-called “advertising inventory”, i.e. the advertising space, for Burda and the Klambt Group. Now the marketing for Funke’s media is also to be added. Competitors such as plaintiff Heinrich Bauer Verlag, Axel Springer and Wort & Bild are not amused. The Bundeskartellamt had cleared the merger in a lengthy decision (186 pages) and did not object (case V-31/22, 16 March 2023).

When I first heard about the case, two thoughts flashed through my mind: Firstly, I thought of the exception in Section 30 (2b) of the German competition act GWB. We had introduced the rule to fulfil the wishes of the press. It was to receive an exemption from the ban on cartels for “co-operation in the publishing industry insofar as the agreement enables the parties involved to strengthen their economic basis for inter-media competition”. At the time, we had already discussed what repercussions this legislative commitment to co-operation between publishers would have for merger control. In this case, however, I was able to confidently put this idea to one side:

“The planned joint marketing of advertisements as a publishing co-operation would in principle be exempt from the application of Section 1 GWB [the ban of restrictive agreements] pursuant to Section 30 (2b) GWB. In the present case, however, in view of the amount of sales with customers from other EU countries, it can be assumed that trade between Member States is affected and thus Article 101 TFEU is applicable.” (Decision of the BKartA, para. 17)

Of course, when two industry giants like Burda and Funke join forces, it will be scrutinised under European law, so the gifts from German politicians won’t help much. You can make a note of this for the planned 12th GWB amendment.

Advertising in the age of big tech

The second thought was: Can such a co-operation really be a problem when it is so obvious that advertising revenues are migrating to the Internet?

Perhaps I was a little biased, as I had just heard a lecture by Martin Andree, who wrote the book “Big Tech muss weg” (Big Tech must go), a slogan that I generally sympathise with. Andree assumes that media with a real editorial team (as opposed by intermediaries simply displaying third-party content) will account for less than 25% of the media landscape by 2029. A negative tipping point would then be passed, according to Andree. Game over for traditional media – unless there is a major change of direction: “Big Tech must go”.

At the Higher Regional Court: Not a word about Big Tech in the entire hearing. Not a word about the fact that Meta rakes in over 100 billion dollars a year in advertising revenue or Alphabet over 200 billion dollars. (However, Google also has to cede around a third of its revenue from advertising on Google Search to Apple, as we have just learnt from the Google trial…) Just for comparison: Hubert Burda Medien generated revenues of 2.92 billion euros with all Group businesses in 2022. So are the digital intermediaries systematically eating up the advertising revenues of the beloved German publishers?

However, it is not quite as clear as one might think just how dramatic the figures are for German publishers at this point of time. And the market definition under competition law is not so simple that keyword advertising on Google and an advert in the printed TV magazine Prisma can easily be equated.

The Bundeskartellamt does its work soberly, and it goes like this: “We look at the people,” explains Dirk Möller from the Amt, who investigated the case. What he means by this is that the services must be exchangeable for the customers (i.e. the people) according to the known criteria, and the markets are defined accordingly without regard to hype.

SuperIllu, SuperBranche

Those who work at the Bundeskartellamt can be lucky or unlucky with their industries. The job that Möller got here is probably one of the more pleasant ones (although, of course, merger control in dental milling machines (current case: B3-107/23) or manure cultivators (B5-129/23) is also fun). In the present case, Decision Division V was allowed to delve into magazines and delineate who reads what and who advertises where. Burda alone publishes 150 magazines in print (including Bunte, SuperIllu, TV Spielfilm), Funke 38 (e.g. HörZu, TV-Digital and Bild der Frau).

Until this hearing, I honestly hadn’t realised where the music is played in the German print market, which is the cash cow of these companies, a pearl of the journalistic guild, for which we love and respect the freedom of the press: It is the “pharmacy customer magazines” (In German, that is of course one word with nine syllables. Judge Breiler: “Excuse me, but that word is a real tongue twister.”) When I wanted to study this segment in more detail after the hearing at the Higher Regional Court, I discovered that the pharmacies in Düsseldorf were on strike that Wednesday, so my market research had to be cancelled for the time being. The next day, I learnt that pharmacies have their own shelf with free magazines, information brochures and flyers, which I had previously ignored, and which really doesn’t have to hide behind the shelf with comfrey root fluid extracts.

His flame is called Karina

Germans learn to love pharmacy magazines at young age when they start reading medizini, a kids’ journal. The lovely posters of young animals covered the walls of all classrooms when I went to school. (Medizini is still around today, and the November issue features a very cute ibex!) Medizini is part of Apotheken Umschau (Verlag Wort & Bild), the magazine for which the Bundeskartellamt claims a circulation of 7.4 million and which is the market leader in this segment with 69 % of advertising revenues. As an editor of “Wirtschaft und Wettbewerb” (WuW), a journal that – in my view – is not too bad either, I am more or less a specialist in this field and I am green with envy! The number of editors listed in the masthead of Apotheken Umschau (I stopped counting at 50) exceeds that of WuW (3 in a very generous counting) many times over. Perhaps WuW should also feed young readers with cute animal posters and give seasoned readers an interview with aging entertainment stars like German TV legend Thomas Gottschalk? (Gottschalk is dating a controller named Karina from Baden-Baden who dragged him to a singing shaman, even though he doesn’t believe “in all this fumigation and yoga wisdom”! That’s what I learned from my market study!)

Health additives and/or mail order business

Companies that apparently have few alternative options advertise in this environment of high-quality editorial content. The Bundeskartellamt’s decision on the definition of advertising markets states:

“The Bundeskartellamt’s investigations in the present case and in the more recent proceedings of the last four years confirm that, from the advertisers’ point of view, there is no interchangeability between the different media types. However, the investigations have certainly shown that the customers surveyed book different types of media (…).” (para. 148)

There is also no single print advertising market. A distinction is made between newspapers and magazines. In the relevant segment of general-interest magazines, the agency states that

“The investigations have shown that there are clusters of advertising customers with regard to advertising priorities in various magazine categories. It can be seen that advertisers from the “health additives” and/or “mail order” sectors are particularly relevant customer groups in the categories of TV programme guides, TV supplements, yellow press and pharmacy magazines (b). The net CPMs [cost per thousand] of these magazine categories at least do not require allocation to different markets (c); the four magazine categories are also sufficiently interchangeable from the customer’s point of view (d), so that the assumption of a uniform advertising market is justified. The limited flexibility in switching offers also does not justify a further delimitation of the relevant market (e).” (para. 203)

This means that anyone who wants to advertise chewable tablets for cold sores or ginkgo pills for memory loss is unlikely to do so in SPIEGEL which is not read by the elderly ladies to be addressed here [I am quoting from the hearing.] But will certainly choose between FreizeitRevue (yellow press), myLife (pharmacy customer magazine) or FunkUhr (TV magazine). This market definition (too narrow, according to the parties to the merger; too broad, according to the competition) results in BCN’s market leadership.

No prohibition

This is a case with considerable risks and side effects. This becomes clear when reading the summarising assessment of the agency:

“The relevant advertising market is oligopolistic (aa), but not without competition (bb). Although potential competition hardly plays a role (cc) and the market is not monopolistic (dd), BCN will become the market leader as a result of the merger, but without achieving a dominant position on a single market (ee). Likewise, despite the fulfilment of the statutory presumption thresholds, no creation of a collective dominant position is to be expected (ff). The examination of unilateral, horizontal effects beyond market dominance (the so-called “SIEC” test) revealed indications of the risk of a significant impediment to effective competition. As a result, however, this risk did not manifest itself sufficiently clearly after the investigations carried out (gg).” (para. 307)

An oligopoly, a new market leader, indications for a risk – and yet no prohibition. No wonder Bauer is fighting. The arrow diagram in para. 255 of the official decision becomes the centrepiece of the 54 minutes before the Cartel Senate. It visualises which “chains of substitution” are at work. Chains of substitution, dear students, exist if product A and product C are no substitutes, but both are substitutes with product B. Then the possibility of substitution via B can lead to all three products being allocated to the same product market (see para. 57 of the 1997 Guidelines on market definition). This is also the Bundeskartellamt’s view here: Pharmacy customer magazines have a certain substitution with the yellow press, which in turn has a certain substitution effect on TV magazines, it makes a chain. Irene Sewczyk, the head of the decision-making division, once again explains very clearly how these chains came about. Somewhere, she says, you have to make the cut, of course. Yes. Market definition is not just empirical, but also has a grain of normative judgement in it.

No complaint

The Senate states that there is much to suggest that this is not objectionable and that nothing significant has been overlooked. The aspects mentioned by the agency also argue against the market shares being too problematic here. There is no gap case for the SIEC test; this can only be considered if there is an oligopolistic structure and there are non-coordinated effects.

The Heinrich Bauer publishing house sees things differently, as lawyer Steinvorth (who came with associate Jan-Hendrik Fitzl) explains with the necessary urgency. In his comments on the SIEC test, Ludger Breuer from the Bundeskartellamt’s litigation department also gently hints that the Senate could perhaps adjust its wording. The SIEC test is still a “delicate plant”, Breuer says. Incidentally, it seems to me in this hearing that Breuer is following in the footsteps of his superior Jörg Nothdurft, the Office’s star pleader, in terms of eloquence, speed of speech and a fine touch of irony.

Done

Only once does Breuer slip up when he talks about “forced labour” that could be imposed on the Bundeskartellamt. Of course, this is far from the minds of both the court and any well-meaning observer who knows how hard the officials in Bonn are working (and what the connotations of the German word “Zwangsarbeit” are). The background is as follows: the plaintiff had not only challenged the clearance decision and demanded that the merger application be prohibited or in any case reconsidered, but Bauer had also asked for action against a separate marketing agreement. This agreement is subject to scrutiny under Art. 101 TFEU. According to the plaintiff, the officials should be obliged to prohibit it – even though they enjoy discretionary powers. According to Breuer, this would have been “forced labour”. The indignant undertone is very audible in his voice. After all, the plaintiff could go to court by way of private enforcement and obtain an injunction against this marketing agreement. Breuer is probably right that there is no basis for such a claim to force the Bundeskartellamt to look into a matter. The Court has repeatedly rejected similar requests.

You can now browse past contributions to this blog in the DKartJ – and it is easier to quote from there, too: http://d-kart-journal.hhu.de/

After the cartel office team, Donata Beck is allowed to speak briefly on behalf of BCN. She sees “immense substitutive movements” at work and rubs it in to Bauer that the company itself is part of a similar marketing cooperation and is the market leader here and there anyway. After her brief remarks (the chairman had already taken a critical look at the clock on the wall), she didn’t even have to touch the large blue and white bottle of water in front of her. The BCN team with in-house counsellors Maximilian Preisser (Burda) and Carsten Bronny and Eva Heneweer (Funke) can sit back and relax. Gerald Mai and Christoph Vaske, their colleagues from Heinrich-Bauer-Verlag, did not land a scoop for their papers today.

The Senate whispers briefly, then the date of the announcement is set for 6 December 2023. You can guess how that will turn out. After Judge Breiler has closed the hearing on BCN, the lawyers shake hands and switch on their mobiles again. In their inboxes they find a new media release by the Bundeskartellamt: The cooperation between OpenAI and Microsoft is not a case for German merger control.

Disclaimer: I had to present the trial here in a condensed version.

Prof Dr Rupprecht Podszun holds the Chair for Civil Law, German and European Competition Law at Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf.

One thought on “In court: Pharmacy customer magazines”