Two Christmas gifts: DMA and GWB10

At the end of the year, the legislators have mercy with the competition law community: The EU Commission published the draft for the Digital Markets Act right in time to take it into the Christmas break. The German Parliament left the stage to the lawmakers in Brussels and did not pass the 10th amendment of the German competition act. The MPs seem to hesitate. Dr. Thomas Lübbig and Ole Schley take a closer look.

2020 was a year in which “Big Tech” was put through a lot in terms of competition law. Almost every week, competition authorities around the globe opened new proceedings. In the EU, everything was heading for the climax at the end of the year with the presentation of the draft regulation on the Digital Markets Act (DMA-D) in a joint effort by the Commission’s Executive Vice President Margrethe Vestager and her Commissioner colleague Thierry Breton. As recently as summer 2020, a New Competition Tool (NCT) had been announced to make time-honoured competition law fit for the digital age.

After several delays, the time for the publication of the new rules had come on 15 December 2020, and the result was rather surprising. According to Competition Commissioner Vestager at the accompanying press conference, the NCT has been integrated into the DMA-D. The draft law also provides for enforcement powers that are more than somewhat reminiscent of the competition instruments contained in Regulation 1/2003. However, the NCT is no longer mentioned in the draft regulation itself. Instead, the DMA-D, now based solely on the internal market competence of Art. 114 TFEU, makes it clear that it is not competition law in the classic sense, nor does it want to be.

A new regulatory approach

Cumbersome, case-specific, ineffective – the accompanying materials to the DMA-D are not exactly full of praise for the previous competition practice under Art. 102 TFEU in the digital sector. For this reason, the paradigm shift in enforcement – the subject of much speculation in the run-up to publication – is now likely to take place.

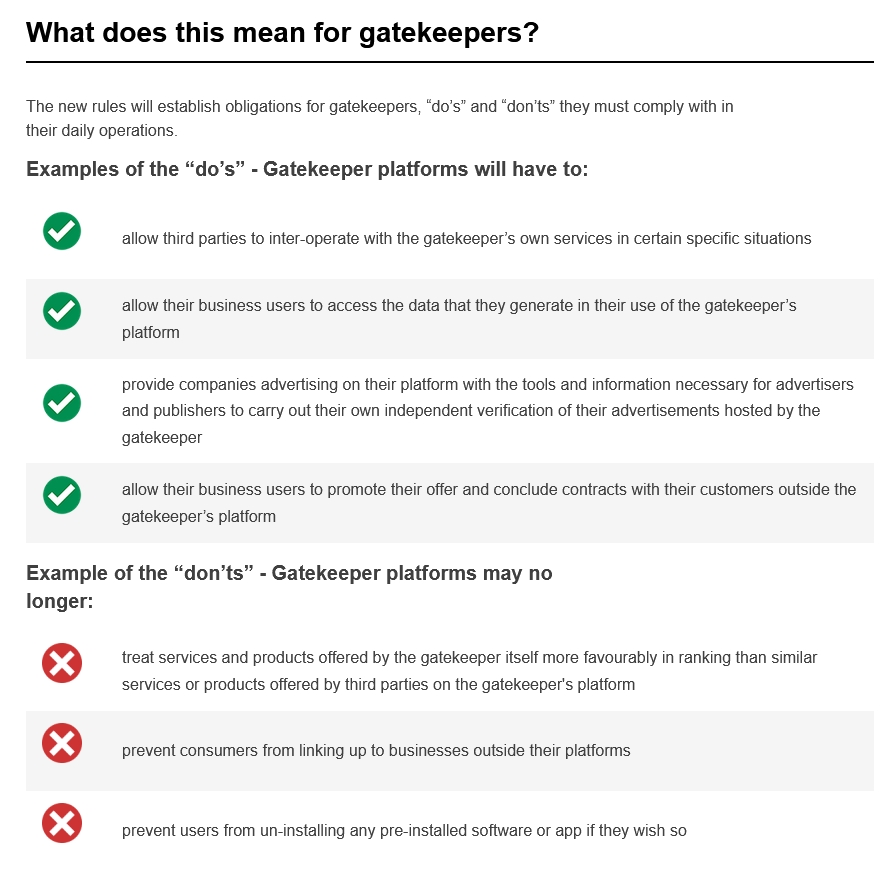

Current and emerging gatekeepers will no longer only be subjected to an ex-post examination of individual cases based on prior abuses of dominance. Rather, the Commission will adopt an ongoing system of monitoring. Once a company has been classified as a gatekeeper by the Commission on the basis of the criteria outlined in more detail in Art. 3 DMA-D, it will be subject to the more extensive behavioural requirements in Art. 5 and 6 DMA-D. Under these requirements, gatekeepers are prohibited by law from engaging in certain practices, such as self-preferencing their own services in relation to those of their competitors.

The interesting question now is what object of protection the DMA-D is meant to pursue. The Commission has not chosen Art. 103 TFEU as its legal basis. Protecting competition in the classic sense of Art. 101, 102 TFEU, as known and appreciated by antitrust lawyers, is not at the core of the new set of rules.

Rather, the DMA-D proposes a new concept of market openness, which ultimately relates to the “contestability” of existing market positions at any one time. Recital 10 of the DMA-D states:

“This Regulation [aims] to ensure that markets where gatekeepers are present are and remain contestable and fair, independently of the actual, likely or presumed effects of the conduct of a given gatekeeper.”

The ultimate aim of this Regulation is therefore to create sector-specific regulatory law, similar to the specific approach taken in sectors such as telecommunications.

And what will become of competition law?

In Recital 9 of the draft text, the European Commission emphasises that the new gatekeeper regulation is “complementary” to the application of European and national competition rules, and that the application of these regulations is “without prejudice” to the DMA. This wording is similarly adopted in Art. 1(6) DMA-D.

But the devil may be in the details. Art. 1 (5) DMA-D, the accompanying materials and the chosen legal basis make it clear that it is seeking full harmonisation within the scope of the gatekeeper regulation:

“Member States shall not impose on gatekeepers further obligations by way of laws, regulations or administrative action for the purpose of ensuring contestable and fair markets.”

Accordingly, a clause to the effect of Art. 3 Para. 2 Sentence 2 of Regulation 1/2003, which permits the application of stricter provisions of national law on the abuse of dominance in competition law, is sought in vain.

The Commission evidently considers isolated solutions that could arise as a result of national regulatory regimes imposing stricter requirements on gatekeepers, to be both a danger to the digital single market as well as a reason for the comparatively small number of large European companies in the digital sector (Lübbig, NZKart 2020, 494 (495); SWD 2019, 444 final, p. 45 et seq.).

Ultimately, this could mean that divergent, above all stricter, national approaches to regulating platforms could only have a limited scope of application for national gatekeepers. The European Commission, in any event, seems to be preparing (for now?) for this scenario, with a unit with 80 full-time staff to be set up for gatekeeper regulation to enforce the DMA. A system of parallel national units with similar DMA-related responsibilities, akin to the network of national and European competition authorities, is not currently envisaged.

Possible effects on the 10th amendment of the German competition bill

With changing perspectives from Brussels to Berlin, there are potential implications for the 10th amendment to the German Act against Restraints of Competition (ARC), the “ARC Digitization Act” (or #GWB10 as it is often called in this blog). This piece of legislation also contains a number of new provisions on the platform economy, such as those relating to “undertakings with paramount significance for competition across markets” (§ 19a), the concept of intermediary power (§ 18 (3b)), and an element of intervention to prevent the so-called tipping of markets (§ 20 (3a)). The practical scope of application of these standards will largely depend on how the specific responsibilities of the DMA-D are negotiated in the further legislative process involving the European Parliament, the Council and the Member States – and perhaps also on how responsibility within the Commission will ultimately be distributed between the involved Directorates General involved so far, namely Competition, Grow and Connect.

The effects on the ARC Digitization Act are already becoming apparent. Final discussions in the German Parliament, planned for 17 December 2020, were cancelled at short notice. The primary reason for the postponement was likely attributable to a constitutional concern about the permissibility of shortening legal protection for, of all things, the new “undertakings with paramount significance for competition across markets” pursuant to section 19a of the draft Act. It had been planned, in the final minutes, to cut out a judicial level by directing the appeal to the Federal Supreme Court (BGH). But in addition, the Government factions in the German Parliament have clearly identified the conflict with Brussels in a motion for a resolution (printed matter of the Committee for Economic Affairs and Energy 19(9)905 of 15 December 2020). There, they call for an “opening clause” in European law, and demand for the German Government to work within the legislative process for the DMA-E to grant national regulations and competition authorities a role in implementing European rules.

This gives a forewarning of the political disputes that are likely to be encountered in the course of the further proceedings. The competition and regulatory law agenda for 2021 thus seems to be set – and “Big Tech” remains front and centre.

Dr. Thomas Lübbig is Of Counsel in the antitrust practice in Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer’s Berlin office as well as Head of the Austrian antitrust practice.

Ole Schley is an Associate in the antitrust practice in Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer’s Dusseldorf office.

The article reflects the personal views of the authors only.

3 thoughts on “Two Christmas gifts: DMA and GWB10”

Sehr instruktiver Beitrag