SSNIPpets 39: Basteln und bauen

The time of working from home is for many people a time for DIY – the author of these lines met a well-known Düsseldorf antitrust law partner in the very long queue to a DIY store on a Corona-Saturday. The European Commission is also currently working on all kinds of things. And the courts are anyway. Time for a workshop report by Rupprecht Podszun. Here are his SSNIPpets – small but significant news, information and pleasantries – our pet project!

Virologists vs. ultra virologists

While the ordinary world indulges in the competition of the virologists, we do ultra-virology at D’Kart. (Excuse me, but this pun had to be done!) Peter Meier-Beck, chairman of the Cartel Senate of the German Federal Supreme Court, had put his fellow judges of the Federal Constitutional Court to the test in this blog after they had made their ultra-vires decision with a 7:1 majority. As a reminder, the German Bundesverfassungsgericht had described a ruling of the European Court of Justice, which it had requested itself, as “not at all comprehensible” and then declared it to be non-binding. The subject matter of that case had concerned decisions of the European Central Bank.

[Since I know that the readers of this blog include proven Latin experts, I will make it clear right away: Virus goes back to virus – the poison, ultra-vires on the other hand to vis, vires – the power. Ecce!]

Meier-Beck’s intervention caused a sensation, his contribution in D’Kart was taken up in such exquisite media as the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, the Politico newsletter, German law magazines such as JUVE and LTO, and numerous European blogs and newspapers. Judge-rapporteur Peter M. Huber apparently felt compelled to explain his verdict in two German newspapers, and that is very very unusual for a judge to explain a judgment just made in the media (instead letting it speak for itself). (For those reading German, the SZ interview is really interesting).

In view of our success in the market with expertise in constitutional law, we are considering a change in our product portfolio. This would also be supported by the fact that demand for antitrust law will decline significantly in the years to come (more on this in a second). However, the fact that there is a market leader dominating the field (the excellent Verfassungsblog) speaks against this. We would be too afraid of being crushed by the grand ordinaries of constitutional law or eliminated by a killer acquisition.

The schism in legal doctrine

However, a change to constitutional law is also not necessary in this case. Although the word “competition” does not appear in the contribution by Peter Meier-Beck, he did write about antitrust law in the end. For what the Second Senate of the Federal Constitutional Court criticised about the judicial control of the ECB can be easily transferred one-to-one to European competition law. This is spelled out in detail in a text in the June issue of the journal NZKart by competition law professor Thomas Ackermann, who – an interesting parallel to the “judges brawl” (Politico) – is a faculty colleague of Peter M. Huber at Munich’s Ludwig Maximilian University. (Huber is a sitting judge and a law professor at the same time). Let it sink in for a second that the German Bundesverfassungsgericht (or any constitutional court in Europe) could question the application of EU competition law on this basis.

In my view, the case reveals a schism between business law experts and some scholars of constitutional law: for some, European law is a daily bread-and-butter business, a matter of course. “We constantly live in Union law”, as cartel judge Jan Tolkmitt of Bundesgerichtshof once put it in the competition law journal WuW. For part of the doctrine of constitutional law, on the other hand, European law is an institutionally independent subject matter that raises questions of sovereignty, legitimacy and nation – ideas that others have overcome or suppressed. The complex relationship between EU law and national law, which eludes conventional categorizations, has certainly not yet been finally unraveled, and is constantly evolving. However, as Meier-Beck has very aptly pointed out: The key to resolving this complexity is certainly not to deny a court that one considers to have jurisdiction oneself (the ECB question was referred to the ECJ for a preliminary ruling!) this very jurisdiction on the grounds of inadequate reasoning on an issue of proportionality.

For the time being, last word on the “judges brawl”

I spent one semester listening to public law with the then-constitutional judge Udo Di Fabio in Munich. To judgments which, in his opinion, were misguided, he exclaimed in high dudgeon: “That’s pretty steep!”

His statement in the daily Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung recently was not so emotional. But Di Fabio did formulate a nice last sentence, which we are appropriating here:

“So let us strengthen the Union as an area of freedom, prosperity and peaceful cohesion by not exaggerating its latent conflicts and by seeking a final strike in this matter where negotiation processes, networks and flexible hierarchies have hitherto characterised everyday life.”

That is very much in line with my wishful thinking. The fact that Di Fabio in the text blames the EU Commission for the escalation of the conflict is okay for a former constitutional court judge who paved exactly this way with his Lisbon ruling in 2009.

Cartel Office as a model

I’ll get to antitrust law now. Some have interpreted the decision of the German Bundesverfassungsgericht as the rise of an institution that realises its loss of importance. The seven judges, so some people assume, who accused the ECJ of incompetence and a lack of competence are angry with submitting to a European court.

The constellation is known from competition law: In the Bundeskartellamt, once the antitrust enforcement pride of the world, it was noticed at some point that the big, exciting cases are increasingly being dealt with in Brussels, and that the EU Commission can even take cases away if the national competition authority does not play according to its rules (Article 11 (6) of Regulation 1/2003). This caused nervous nagging self-doubt with some people in the Bundeskartellamt, or so it was my impression in the years surrounding the adoption of Regulation 1/2003. In the meantime the Bundeskartellamt has found its role. Of course, there are tensions with EU Commission, but on the whole the relationship seems amicable and competition of the enforcers is a productive one: the Bonn authority takes on a pioneering role with many breath-taking interesting proceedings; it is concocting statements and concepts with other national enforcers; it influences the International Competition Network. The German legislator assists, for example with the transaction volume threshold in the 9th amendment to the German act or with the plans for the 10th amendment. The Commission, not to be outsmarted, seems to get along well with that.

The abolition of antitrust law

The question of the hour is: Who needs it competition law any more? Who still needs competition when it comes to reviving the European economy post-Corona? Apparently Mrs Merkel and Mr Macron do not. They have spoken out quite unequivocally in favour of European champions and changes to competition law that may go to the very roots of our discipline.

A first test case for championism was the fight for the competitive conditions for Lufthansa. When the German government decided to enter the cockpit of Lufthansa in an act of saving the national carrier, The EU Commission decided it was time to break the dominance of this now partly state-owned airline at the hubs of Frankfurt and Munich. Yet, the airline resented, and the EU Commission was only partially successful. The reports on the matter testify to a certain chutzpah on the part of the close-to-failed company.

It would now be easy to sing the high song of free competition here. I don’t want to make it that easy for myself. But if we are to think about a new industrial policy, I would find it much easier if the calls for protectionism were accompanied by

- the emphasis on a truly European approach,

- proposals to revive the ailing multilateral trading system,

- a tough innovation and digitisation initiative.

Yeah, yeah, I’m sure it’s all in conceptual papers. Still, an innocent bystander like me can’t get rid of a stale taste in his mouth.

Ad personam: EVP Vestager

Since we were just at Margrethe Vestager’s place – a little bit from our glamourous “People section” is all you can ask for, and there we start with the most important one: Vestager will give the keynote speech at the conference of antitrust law scholars, organised by the Academic Society for Competition Law (ASCOLA) on 26 June 2020. As a co-organizer of this digital substitute for the meeting that was actually planned for Porto, I am really looking forward to it. Apart from this one highlight among many, around 90 lectures by scholars from all over the world will be flicking through the internet in three days. You may give a “wow”!

German media analyst Kress recently ranked Vestager as the most powerful string-puller in the media business – ahead of Nathanael Liminski (a politician) and Mathias Döpfner, the boss of Springer, the publisher-turned-digital company. Andreas Mundt ended up in sixth place. Not too bad, either.

Vestager is also present in the media in other formats: “Borgen”, the Danish series that tells the story of the rise of a Danish politician and has a real-life role model, is being continued. Probably soon in the in-flight entertainment programme of an airline of your choice (or the one available at your hub).

Finally, this message electrifies us: Margrethe Vestager was a guest judge on the Greek TV show “Greek MasterChef”, where they cook against each other. An obvious cast! Who, if not the competition commissioner, should please decide a cooking competition? Here you can find the trailer of the show. We are curious in which German TV show Vestager will award points soon!

From farm to fork

In addition to the flood of state aid decisions, Brussels remains active in the field of antitrust law. The Policy Division is making progress with the revision of the vertical BER and is working on horizontal issues. A small request from the scientific community: documents (such as the summaries of the consultations) should indicate a date, perhaps even the author. And, while I’m at it: the DG’s website could be reorganised, cleaned up and equipped with a helpful search function. Or is it just me?

Another Directorate-General of the Commission has presented the “Farm-to-Fork” strategy. The aim of this strategy is to establish “sustainable food systems” that will halt climate change etc. It reveals as a plan for the 3rd quarter of 2022:

“Clarification of the scope of competition rules in the TFEU with regard to the sustainability in collective actions”.

Enjoy it. Maybe that can also make an entry under the heading of “The abolition of antitrust law”.

The new tool

The real bang is a consultation launched by the Commission, which could set up a whole new European competition system. Ladies and Gentlemen, please rise for “a possible new competition tool”.

This is a Brussels spike – an attempt to overtake the German competition bill amendment (which is currently still idle) and the British CMA. The press release describes the idea of this tool in this way:

“After establishing a structural competition problem through a rigorous market investigation during which rights of defence are fully respected, the new tool should allow the Commission to impose behavioural and where appropriate, structural remedies. However, there would be no finding of an infringement, nor would any fines be imposed on the market participants.”

The Commission thus envisages a kind of sector inquiry, as a result of which it imposes behavioural or structural remedies. No infringement necessary, no dominance. Of course, the rights of defence are fully respected. A first reaction could look something like this.

(The link leads you to Giphy, by the way. The company behind this website is currently being acquired by Facebook. This is where the Commission could show, if it can and wants to, how to handle traditional tools in its toolbox).

As chance would have it, a few days ago I got the PhD thesis of one of my students for review entitled “Market structure abuse in the platform economy”. Dear author L., I am hurrying with the review so that I am able to speak about the “new competition tool” – and so that this thesis is published before it is too late. (Disclaimer: Statements of this kind by doctoral supervisors are always non-binding declarations of intent).

Phase III

The Commission also was also active in cases: at the end of May, it withdrew the obligations it had imposed on the pharmaceutical company Takeda in the context of a merger control review in 2018. A business unit for a drug was to be divested, which apparently proved to be difficult and Takeda requested that the commitment be lifted. This waiver was granted by the Commission. The decision is not yet out, only a press release.

Amendments to remedies are possible – an ICN document from 2016 cites two Italian cases as examples, and a book which I happen to have at hand, refers to the Bombardier/Adtranz merger of 2001 as an example. Revocation is possible only under “exceptional circumstances” (see paragraph 73 of the Remedies Notice).

The Takeda case casts a spotlight on the post-merger control phase, phase III, if you wish so, which is too seldom the focus of attention. Which conditions work? How long does it take? What are the relevant parameters? A systematic ex-post evaluation of decisions by competition authorities would be helpful.

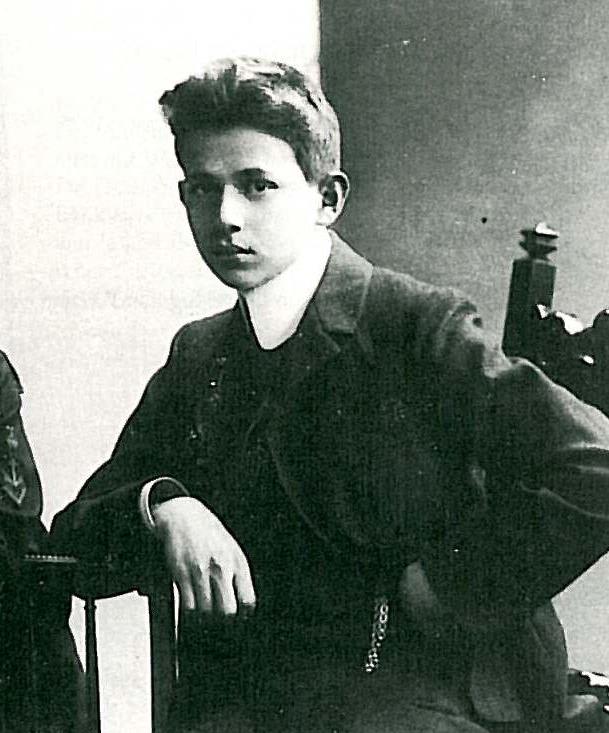

The grand German author (and lawyer) Kurt Tucholsky once wrote in his inimitable style about the end of merger proceedings. Or, to be exact about the point when in movies the man and the wife finally merge. This is a translation by Kurt Ross, you get the idea:

“Most movies in their final scene,

fade happy-ending from the screen.

One briefly sees the lady’s lips,

brushed by the hero’s mustache tips.

So now, at last, they tie the knot –

and then what?”

For more see here.

No end in sight

If you were hoping for a happy ending here (Podszun, now stop for today, I want to go, eh, well, home!), I have to disappoint you once again. Because with these first SSNIPpets after our excursion into constitutional law, the last word belongs to the courts:

- Today, the EU Court is hearing the ISU case on ice skating. The always entertaining Lewis Crofts (MLex) reports on Twitter about an “obsessed judge”. Could be an exciting decision.

- On the ruling, in which the Court overturned the prohibition of a British telco-merger, we let Pablo Ibanez Colomo of Chillin Competition take the lead, who speaks of a new “Airtours” moment.

- Two major proceedings are still pending before the German Bundesgerichtshof: The Cartel Senate has allowed dominant ticketing platform CTS Eventim to seek redress for a banned merger with the agency Four Artists. The intention is to examine whether the strengthening of a dominant position must be significant for the Bundeskartellamt to stop a merger.

- In the Facebook saga (that’s right, we could also hear something new about that!) the Bundesgerichtshof will hear the case in summary proceedings on 23 June 2020. Fun fact: In the announcement, the relevant rules mentioned are first of all those of the GDPR (which the Düsseldorf Higher Regional Court had not examined at all).

The German competition act has been amended. Sometimes that goes really fast. This was by the Act on Mitigating the Consequences of the COVID 19 Pandemic in Competition Law and for the Self-Governing Organisations of the Commercial Sector of 25 May 2020 (BGBl I 2020 1067), which came into force on 29 May 2020.