Conglomerate foreclosure in the metaverse

The concept of the metaverse has received a lot of attention over the last year. Some assume it will revolutionize the way we live, others believe that it merely constitutes the mainstreamization of video gaming. This uncertain outcome has not discouraged undertakings to invest substantially in the metaverse. These investments, accompanied by the increasing concentration in gaming markets, warrant a closer antitrust discussion of the metaverse. Whilst interoperable platforms and ecosystems tend to provide significant value to consumers, their layered markets are increasingly challenging for antitrust law to address. Dwayne Bach and Fabian Ziermann discuss concerns related to conglomerate foreclosure that may arise in the metaverse.

First, what is the metaverse?

Intuitively, one associates the metaverse with Mark Zuckerberg and his decision to rename Facebook Meta. In doing so, Zuckerberg shared his vision of what the metaverse may look like in the future. Zuckerberg sees the metaverse as the next stage of the internet, where almost every real-life interaction can take place virtually through an avatar. Whether shopping, team meetings, events, gaming, learning, working, watching movies, planning home furnishings – everything takes place in the metaverse. This vision includes the possibility – in the context of sports – to train with others as holograms by utilizing VR glasses. However, this is not the only approach towards creating a metaverse. Some platforms adopt a gaming approach (e.g., Roblox). Others focus on virtual real estate purchasable as non-fungible tokens (e.g., Decentraland), or on customized metaverse experiences for businesses (e.g., Rave Space).

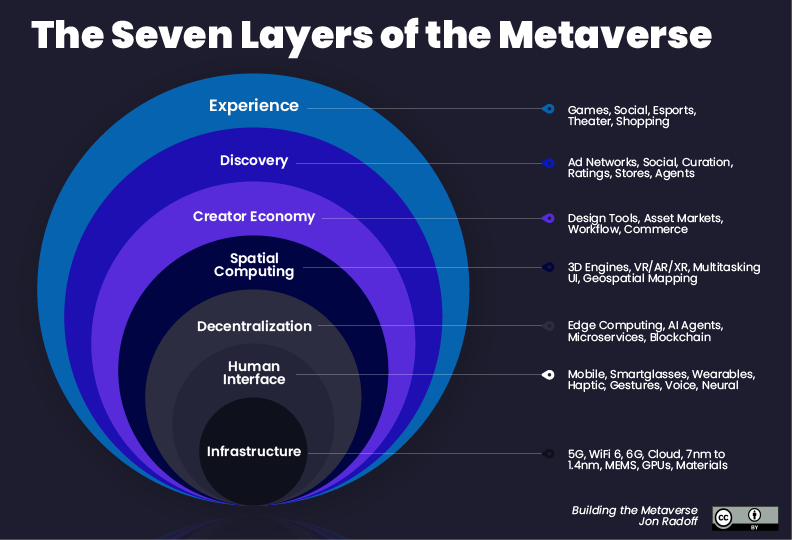

Due to this variety of approaches, no universal definition of the metaverse has been adopted. Some compare it to the beginnings of the internet. However, while the current projects provide a glimpse of the opportunities associated with the metaverse, it is also possible that a fully interoperable metaverse will never come to be. Instead, we may be faced with a multitude of platforms, operated by various companies, which may obtain gatekeeper status for the purposes of the DMA. As it is uncertain which platform or technology will prevail, a precise definition of the metaverse does not seem feasible at this stage. However, the existing approaches provide likely structures of metaverse ecosystems. These structures include different layers, which are comprised of multiple building blocks. As greater certainty exists in this regard, we shall focus on these different layers for a first antitrust analysis.

Building blocks of the metaverse layers as antitrust markets?

As the graphic above illustrates, a metaverse platform usually has seven layers. Each layer consists of several building blocks. For instance, the experience layer is comprised of the building blocks gaming, virtual concerts, virtual fashion, virtual real estate, and virtual work. In terms of antitrust market definition, these building blocks may constitute separate – yet complementary – relevant product markets or, as illustrated by Epic Games’s metaverse platform Fortnite, may be merged into one relevant cluster market. The building blocks and the layers together form the metaverse value chain.

What is clear is that the layers themselves cannot be used to delineate the relevant product markets, since this method would substitute markets that are not universally interchangeable from a consumer’s perspective on every metaverse platform. For example, the building blocks shopping and gaming address different consumers, whereas the building blocks virtual concerts and gaming may be complementary or interchangeable, as is the case for Fortnite. Alternatively, the building blocks (or markets) of virtual concerts and virtual fashion constitute upstream and downstream markets for the Fortnite platform. The upstream market being concerned with the competition between artists to perform on the Fortnite platform, the bottleneck being Epic Games’s regulation of such concerts on the platform. Thereby Epic can control the downstream virtual fashion market, as it decides which artists will be featured on the virtual fashion market, for instance through in-game skins.

Thus, building blocks will serve as a more useful basis than layers when determining the relevant product market. However, not every metaverse platform is built like Fortnite; hence, the market relationships of layers and building blocks under antitrust law differ, demanding a case-by-case analysis for each metaverse platform.

How these layers and building blocks may become relevant in the context of mergers will be outlined by analyzing a case of input foreclosure. Whilst input foreclosure may also arise in the context of Article 102 TFEU, due to the recent increase in concentrations in the gaming industry we will exclusively focus on merger control.

Input foreclosure

The EU merger regime distinguishes between horizontal and non-horizontal mergers. The latter are subdivided into vertical and conglomerate mergers. Whereas vertical mergers involve undertakings operating at different levels of the supply chain, conglomerate mergers concern undertakings that are in a relationship which is neither purely horizontal nor vertical.

Input foreclosure generally only appears in the context of non-horizontal mergers. According to para 31 of the Guidelines on the assessment of non-horizontal mergers, input foreclosure occurs when “the new entity would be likely to restrict access to the products or services that it would have otherwise supplied absent the merger, thereby raising its downstream rivals’ costs by making it harder for them to obtain supplies of the input under similar prices and conditions as absent the merger. […] The relevant benchmark is whether the increased input costs would lead to higher prices for consumers.”

The following example serves as an illustration of input foreclosure: A produces chips for the automotive industry and supplies them to automotive manufacturers B and C. B acquires A and raises the chip price for C. As a result, C’s input (chips) becomes more expensive, or B may even foreclose C from obtaining its chips entirely. As a result of the increased costs for inputs, C’s vehicles become more expensive, providing B with an anti-competitive advantage, namely higher revenues from C’s inputs, as well as potentially more consumers for B’s vehicles due to the increasingly more expensive vehicles by C. The consumer is harmed in this scenario through increased prices and potentially a reduction in choice, as some consumers may no longer be able to afford C’s more expensive vehicles.

To assess such an input foreclosure, three criteria must be met:

- the undertaking’s ability to foreclose access to inputs;

- the undertaking’s incentive to foreclose access to inputs; and

- whether there are significant detrimental effects on competition downstream.

Whilst input foreclosure regarding vertical mergers is common, it has been difficult to establish in the context of conglomerate mergers. This may change due to the metaverse.

Conglomerate input foreclosure in the metaverse

Whilst foreclosure is mentioned by the non-horizontal merger guidelines as the main concern in conglomerate mergers, it seems to be limited to tying and bundling. However, given the integration of digital conglomerates in multiple layers and building blocks of the metaverse, the following example demonstrates that input foreclosure may become one of the main concerns in relation to the metaverse, as conglomerate acquisitions can distort the entire metaverse value chain.

Assume that two undertakings, A and B, each develop a multi-device metaverse platform. For our purposes this is a game-like platform on which users interact with each other on the experience layer – the first layer of the metaverse. Both platforms monetize in the same way, through a premium model (as is common for such platforms, e.g., Second Life) – requiring users to pay 10€/month – or through a freemium model – requiring users to watch advertisements every 15 minutes.

At some point, platform A decides to acquire a cloud infrastructure provider C, an undertaking which forms part of the seventh layer of the metaverse. A and C will not cooperate for A’s metaverse development. Prima facie this may be an unrelated and unproblematic conglomerate acquisition. C, however, is part of B’s value chain. Following the acquisition, it is assumed that A has the ability to implement input foreclosure through either restricting B’s access to C’s cloud storage or providing such at less advantageous conditions. The question then needs to be asked whether there is an incentive for A to engage in such conduct and whether this has a detrimental effect on the downstream metaverse value chain.

To illustrate, cloud storage is used as part of the human interface, the sixth layer of the metaverse, e.g., virtual reality (VR) glasses. By increasing the cost or decreasing the capacity of cloud storage in B’s value chain, VR glasses will become more expensive or be of lower quality. This in turn affects the virtualization tool’s (Spatial Computing) layer, namely 3D modelling and avatar development, which the user visualizes through VR glasses. In turn, as either the cost or the capacity of cloud storage is affected, the virtualization may become more expensive or be reduced in quality. This makes game development, the first layer, more expensive, as costs have been passed on through the other layers of the metaverse.

Due to the cost increase in its value chain, B is faced with two options. The first option is to be exposed to slow marginalization or changing its business models to compensate for the change in circumstances. Given that metaverse platforms are multi-device products, any offsetting of costs needs to take app store commission fees (as a potentially cost-aggravating factor) into account. This could mean that B either has to increase the price of its premium model more substantially from 10€ to 12€/month or decrease the ad-frequency from 15 to 12 minutes. Alternatively, B may seek to offset its increased value chain costs through nearly undetectable exploitative practices against consumers through the discovery and economic layers of the metaverse, e.g., loot boxes. In any scenario, this results in a more expensive or lower quality experience for consumers on B’s platform, without gaining any improvements. As a result, consumers may switch to A’s platform as it offers a cheaper, less ad-heavy or higher quality user experience, again resulting in the marginalization of B and inducing market tipping in the long-term.

Hence, after a careful examination, the prima facie unproblematic minor conglomerate acquisition may provide a major strategic incentive for A to distort B’s value chain, which as it affects ‘choice or quality of goods and services’ of the platform, negatively influences parameters of competition, as per recital 10 of the non-horizontal merger guidelines. However, given the spread of effects across multiple layers and building blocks of the metaverse value chain, the anticompetitive conduct may be more difficult to establish, or remain entirely undetected. In this context, the question ought to be asked whether antitrust regulators are equipped to detect such behaviour.

Regulatory outlook

The Commission and national competition authorities arguably face a predicament in responding to the challenges of the metaverse. On the one hand, it may not be reasonable to expect the Commission to conduct market inquires or launch investigations in a developing space. On the other hand, the Commission’s late interventions may be the very reason that has set regulators behind in responding to the challenges of digital markets and Big Tech. Letting the metaverse expand and hastily regulating it at a later stage is a laissez-faire regulatory approach that may be unsuitable to address the complexity of the metaverse. At the same time, a premature overenforcement may discourage investments and equally hamper innovation. The current assumption that the DMA will apply to the regulatory issues of the metaverse must be countered with the fact that a multitude of metaverse platform operators are unlikely to meet the quantitative criteria to be designated as gatekeepers under Article 3(2) DMA. Hence, requiring a different approach.

In this context, Vice-President of the Commission Margrethe Vestager recently stated, that it is worth pursuing novel antitrust cases. The approach of combining commitment and interim decisions, as done in the Broadcom case, may provide the Commission with the tools to flexibly regulate the development phase of the metaverse. On the one hand, this provides speedier legal certainty as regulators and undertakings have an increased incentive to engage in a regulatory dialogue to address arising concerns. On the other hand, interim measures provide the Commission with the ability ‘to test the efficacy of a particular remedy’ enabling it to understand the complexities of a sector and avoiding unsuitable remedies.

Dwayne Bach wrote his doctoral thesis on the limitations in copyright and competition law for publishers in esports. He is currently working as a Legal Trainee at Baker McKenzie in Düsseldorf. The views expressed in this post solely reflect the author’s opinion.

Fabian Ziermann is a Pre-Doc Fellow of The Competition Law Hub and a Doctoral Researcher at the WU Vienna, supervised by Vicky Robertson and Andrew Murray (LSE). His research focuses on the regulation of eSports, gaming and the metaverse through comparative competition and IP law. He holds an LL.M. in Competition, Innovation and Trade Law from the LSE.