Miba/Zollern: Ministerial authorisation revisited

Actually, there are no longer any legal disputes about the German special instrument of ministerial permission for mergers blocked by the Bundeskartellamt since the right of appeal was effectively cut off in 2017. Or so we thought. Now the Düsseldorf Higher Regional Court heard the case Miba/Zollern. Philipp Offergeld reports of an entertaining oral hearing.

The legal dispute regarding the establishment of the joint venture between Miba AG and Zollern GmbH & Co KG entered the next round on Wednesday, August 19, 2020, before the Düsseldorf Higher Regional Court (Oberlandesgericht, OLG). As a reminder, the German Federal Cartel Office (Bundeskartellamt) had prohibited the planned acquisition in January 2019 because further concentration in the market for engine bearings was to be feared. We reported here.

The merging parties then applied to the Federal Minister of Economics, Peter Altmaier, for ministerial approval under Section 42 of the German competition act – a special instrument where the Minister may trump the Bundeskartellamt for reasons of public welfare (however ill-defined that term may be). Altmaier granted the requested ministerial approval a year ago, but with some – legally and economically controversial – ancillary provisions. At the same time, he deviated from the Monopolies Commission’s opinion, which had not identified any overriding reasons of public good. The parties completed the merger after the ministerial authorisation was granted, in compliance with the ancillary provisions. The unbiased reader may therefore now possibly ask why there is talk here of a continuation of the legal dispute. For third parties, the granting of a ministerial authorisation is probably no longer contestable after the amendment of Section 63 (2) sentence 2 of the German act anyway (the 2017 reform cut off this possibility after Ministers performed poorly in the Düsseldorf court). Merging parties who receive a ministerial authorisation have no reason to sue. So what did Miba/Zollern want at the OLG?

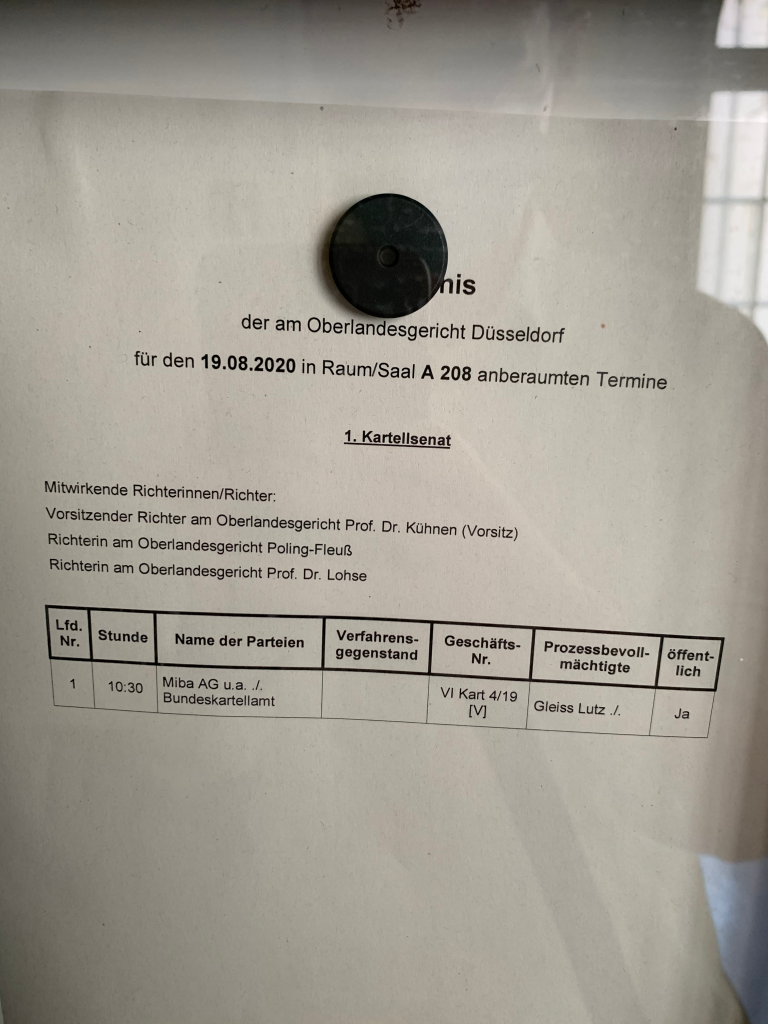

The parties to the merger have filed an appeal with the Düsseldorf Higher Regional Court against the original prohibition order of the Federal Cartel Office – which is actually no longer relevant due to the ministerial approval. The oral proceedings on Wednesday, chaired by Prof. Dr. Jürgen Kühnen (yes, he is the one from that Facebook decision), therefore basically revolved exclusively around the admissibility of the appeal requests. Law firm Gleiss Lutz represented the merging parties, led by Dr Matthias Karl, while the Bundeskartellamt was represented by Jörg Nothdurft, Chief Legal Officer, and Eva-Maria Schulze, Head of the relevant Decision Division.

Unusual negotiation

The oral hearing was unusual in two respects. On the one hand, of course, due to the Corona pandemic, which resulted in a smaller audience area and greater distances between the parties to the proceedings. On the other hand, even before entering the hall it was noticeable that the lawyers had brought along several bearings, which probably made a good weight even for more gym-familiar lawyers. The bearings were initially “dragged” into the hall by two people upon entry. Although the entire hearing was concerned with the admissibility of the complaint and in particular with the interest in the continuation of the proceedings, attorney Karl did not want to be deprived of the opportunity to lift the weighty piece of metal onto the table during the hearing and to reprimand the BKartA for what he considered to be an incorrect market definition. It was wrong to regard plain bearings of completely different sizes as one market, so he said. Industrial antitrust law, with no digital touch – this led to photos being taken with the giant plain bearing in a short interruption of the process.

Why are you even here?

Presiding Judge Kühnen began the hearing with the statement that according to the preliminary assessment of the Senate (Kühnen was flanked by Ms. Poling-Fleuß and Professor Lohse), both the main motion to revoke the prohibition order and the subsidiary motions for a declaratory judgment of illegality (appeal for continuation of proceedings) were inadmissible.

The annulment could not be sought since, due to the ministerial authorisation which has now been granted and the enforcement by the parties on this basis, there is no longer any impact by the prohibition order. An appeal is no longer necessary, so Kühnen’s thought. Due to the execution of the ancillary duties, the execution in the form prohibited by the BKartA was also no longer possible.

Determination interest?

In accordance with general administrative procedural principles, an interest in the continuation of the proceedings must be shown in order to file an appeal for such a decision, which the Senate did not see. Precedent discussed were mainly the preparation of a state liability lawsuit and the risk of recurrence.

If the serious intention of the parties is to assert a claim for state liability, then according to the case law of the Federal Administrative Court this does not justify any interest in a continuation determination if such a claim obviously does not exist. This was the case here, according to the preliminary opinion of the court, since the ancillary provisions issued by the Minister could not be regarded as causal damage if the parties had voluntarily agreed to them. Moreover, they could have first contested the prohibition and, pursuant to Section 42 (2) sentence 3 of the competition act, could only then have applied for ministerial authorisation. The parties could not first obtain the ministerial authorisation and then still take action against the prohibition order, which has meanwhile become obsolete. The discussion revolved much around the relationship between the prohibition order and the ministerial authorisation. Karl asked what would happen if the parties to the merger did not fully comply with the ancillary duties and “blew the ministerial permission”. Then the minister would probably revoke it and the original prohibition order would have to be revived. This model annoyed Judge Kühnen, who described such behaviour as “wanton” and completely out of question. The Senate would not write “legal opinions” for the completely unlikely case of the unbundling of a merger.

Risk of recurrence due to further merger projects?

Nor was there any danger of a similar prohibition order being repeated, since a comparable project would have to be assessed completely differently, at least with regard to market conditions, because of the merger that has now been completed. Moreover, a mere assertion would not suffice for this purpose, but further projects would have to be presented in concrete terms, so the Judge said.

In response to the visible and also communicated annoyance of the Presiding Judge, the merger parties apparently explained in a surprising manner that other comparable merger projects were in the pipeline, which, however, could not be disclosed in a public hearing for reasons of confidentiality. It appeared that this had not been put forward in the written submissions so far. The parties to the merger therefore requested that they be allowed to submit the relevant facts within a period of two weeks. However, no decision on this request was made on that day. Kühnen interrupted the meeting with the words “I will now calm down a little”.

Ministerial authorisation in need of reform?

The procedure shows once again that the ministerial authorisation in its current form is associated with uncertainties. It is unclear whether it will overtake the decision of the cartel office, i.e. whether the ministerial intervention will render it legally invalid. Nevertheless, the minister should be bound by the findings of the Bundeskartellamt, e.g. regarding market definition. Whether this is true is questionable, but in any case the existence of a prohibition decision is a prerequisite for the granting of the ministerial approval. The logical way seems to be to first challenge the prohibition order and, if unsuccessful, to ask the minister for help (a variant that was also discussed in this and similar ways during the reform of the ministerial authorisation in 2017). However, this is not compatible with the reality that mergers cannot be postponed for years until the Higher Regional Court and possibly the Federal Supreme Court have made a legally binding decision on the case. It is possible that this is one of the reasons why Miba and Zollern applied for and made use of the ministerial approval earlier.

Effective legal protection?

However, this raises a problem with regard to the provision of effective legal protection. The possibility of bringing an action against the prohibition order is useless if it cannot be exercised de facto without thereby abandoning the merger. The parties are put in a dilemma either to challenge the prohibition order and wait for the outcome of the proceedings, which may often lead to the failure of the merger for reasons of time, or to agree to a ministerial authorisation, which may be based on erroneous findings and may be associated with highly onerous ancillary provisions. The ministerial approval therefore constitutes a de facto waiver of legal protection. However, if a prohibition order no longer has any factual effect, this could be bearable. In view of the dynamic growth in all sectors, the precedence of a decision by the Federal Cartel Office (which would also be overtaken by a ministerial approval) is likely to be low in the next merger.

The legislator could clarify the relationship between prohibition order and ministerial authorisation for reasons of legal certainty. However, this would not be easy: If it is made clear that despite the (executed) ministerial authorisation, the prohibition order can be challenged and that the ministerial authorisation would also become invalid in the event of judicial annulment, the reversal of ancillary provisions would remain a huge problem. The ministerial authorisation remains an instrument that causes difficulties – and in some cases even annoyance.

Philipp Offergeld is a research assistant at the Chair of Civil Law, German and European Competition Law at the Heinrich-Heine-University Düsseldorf and a doctoral candidate under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Rupprecht Podszun.

2 thoughts on “Miba/Zollern: Ministerial authorisation revisited”

Sehr lebhafter Bericht, der mal wieder klar macht, wie spannend das Kartellrecht sein kann. Vielen Dank

Den Spruch „Rechtsgutachten schreiben wir keine.“ habe ich mir seinerzeit auch eingefangen (EDEKA/Plus). Immerhin hat Kühnen aber damals (zähneknirschend) die Rechtsbeschwerde zugelassen. Beim BGH haben wir dann allerdings auch verloren. Vgl.

https://research.owlit.de/document/1116ba12-a8a6-3c46-bd35-380ccce3517f