Tchibo vs. Aldi-Süd: Coffee Prices in Court

May food retailers offer products below production cost? This question was discussed on Tuesday before the Higher Regional Court (Oberlandesgericht, OLG) Düsseldorf in the proceedings between Tchibo, a leading coffee company in Germany, and Aldi-Süd, one out of the group of four big food retailers in Germany. Klara Dresselhaus reports from the oral hearing.

Dieser Beitrag ist auch auf Deutsch verfügbar!

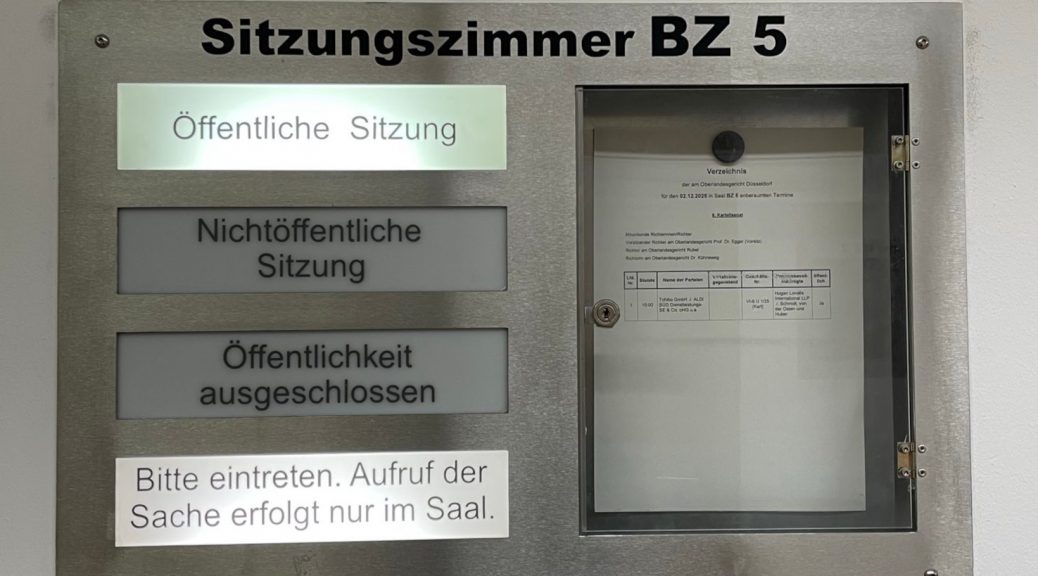

After the Regional Court (Landgericht, LG) Düsseldorf had dismissed the claim in the first instance, the legal dispute went into the second round before the 6th Cartel Senate, chaired by Prof. Dr. Ulrich Egger, on December 2, 2025.

Tchibo demands that Aldi-Süd cease selling its self-produced own-brand coffee “Barissimo” below its production costs. Tchibo is represented by Hogan Lovells, led by Dr. Marc Schweda, while the Essen law firm SOH (formerly: Schmidt, von der Osten & Huber) entered the ring for Aldi-Süd. In the nearly one-hour hearing, it quickly became clear that it was about fundamental legal questions. One thing can already be established: a successful appeal would be surprising.

Rising food prices are on everyone’s lips, these days. The German Monopolies Commission, an independent government advisory board, had recently dedicated an entire special report to competition in the food supply chain. Yet, Tuesday’s proceedings focused on the antitrust permissibility of excessively low prices. Specifically: the prohibition of predatory pricing strategies under Section 20(3) of the German Act against Restraints of Competition (GWB) (see the English version here).

At its core, the case concerns discount campaigns, through which Aldi-Süd repeatedly offered various self-produced coffee products below production cost starting in December 2023. It is undisputed that the offers significantly undercut the cost of the products. In 2024, the discount campaigns affected 7 out of 52 calendar weeks. Tchibo is of the opinion that Aldi-Süd’s business practice violates Section 20(3) GWB. According to Section 20(3) Sentence 1 GWB, undertakings with superior market power over small and medium-sized competitors may not abuse their market power to unfairly hinder such competitors. Such a hindrance of competitors arises from the exclusionary effect of the low-price offers.

Haggling over the Value in Dispute

Prof. Dr. Egger opened the hearing with an exchange about the scope of the plaintiff’s interest so as to determine the value in dispute. “How much less coffee was sold? How should we imagine this?”, the chairman inquired at the beginning.

While the requirement of a drop in sales for Tchibo’s impairment pursuant to Section 33(3) GWB was initially discussed, the appellant and the court agreed that any loss of sales by Tchibo must at least be considered for the value in dispute. Tchibo had originally stated a value in dispute of €150,000, which the LG had set at €300,000 in its judgment. However, the higher court did not find this sum realistic. This should be “far from what the claimed damage is likely to be”.

While lawyer Schweda for the plaintiff emphasized that Tchibo’s specific sales decline was not of greater weight due to the fundamental importance of the matter, the court did not relent. “Are you in agreement with €5 million?”, Prof. Dr. Egger asked emphatically. However, the Tchibo lawyers did not allow themselves to be pinned down. If more specific information about the sales decline were required, they would have to submit it later. The defendant’s side could largely remain reserved in this regard—as in many contentious points. From their perspective, the originally stated value of €150,000 would be closest to the value in dispute, as there had been no sales declines for Tchibo at all, so they said.

General Clause or Standard Example?

The actual core of the hearing revolved around whether, and under what conditions, the sale of self-produced goods below production price in food retail violates Section 20(3) GWB. Particularly controversial is whether the present case constellation is comparable to the standard example in Section 20(3) Sentence 2 No. 1 GWB, according to which the sale of food below cost price is categorically classified as an unfair hindrance. According to Section 20(3) Sentence 3 GWB, this price (the “Einstandspreis” in German) is the price agreed between the undertaking with superior market power and its supplier for the procurement of the goods or service. The standard example therefore initially only covers the acquisition of products from third-party suppliers, not in-house production. Since Aldi produces the coffee itself, an unfair hindrance does not result from a direct application of this standard example.

The start of this part of the hearing was conspicuously theoretical—the participants referred several times to the “legal methodology”. The court initially raised the question of how the plaintiff intended to integrate the evaluations of the standard example into the legal interpretation. Chairman Egger enjoyed this discussion; one could sense that he is also the chairman of the Judicial Examination Office at the OLG Düsseldorf.

The court quickly indicated that it did not consider the requirements for an analogy to Section 20(3) Sentence 2 No. 1 GWB to be met—it lacked an unintended regulatory gap (planwidrige Regelungslücke). Schweda, on the other hand, repeatedly emphasized that a hindrance was not supported by analogy to the standard example —rather, the general clause of Section 20(3) Sentence 1 GWB was violated. Nevertheless, the evaluations of the standard example should be considered: the “negative content” of the business practice in question was identical.

The court countered that an application of the general clause would consequently mean that its prerequisites would also have to be demonstrated—especially an intent to push Tchibo out of the markt on the part of Aldi-Süd. However, this had not been demonstrated. Schweda repeatedly stressed that unequal treatment of self-produced and supplier-acquired products under the predatory pricing rules was not justified. The business strategy was the same, he argued, and characterized by the possibility of mixed calculation in food retail. Capturing this unequal treatment was precisely, so he said, the purpose of the general clause.

The negotiation ran into this duality: either the violation is based on the general clause—with a demonstration of all its prerequisites—or on an analogous application of the broader standard example. A modification of the general clause in light of the standard example, bypassing the analogy requirements, would contradict the normative system. The plaintiff’s side briefly added that intent to exclude could probably be assumed as a subsidiary argument in this case, as it should not be understood too narrowly in the form of what they called dolus directus of the first degree in ancient Rome.

What did the legislator intend?

Irrespective of the “technical” questions of interpretation, the comparability of the behaviour in question with the sale below cost price was discussed. In particular, the will of the legislator when regulating the prohibition of sales below cost price occupied the participants for a large part of the hearing. The defendant’s representative concluded that he had rarely conducted a procedure “in which so much was discussed about the legislator’s intentions”.

While the plaintiff’s representatives primarily emphasized that excluding sales below production costs could not have been intended due to the operational similarity, associate judge Stefan Rubel stressed that the phenomenon of vertical integration in retail has long been known. Nevertheless, the legislator had not adapted Section 20(3) GWB accordingly. The plaintiff’s side, in turn, stressed that the tendency towards in-house production by food retailers did not play such a major role during the last amendment of the standard example in 2007. Egger stated: “We cannot look into the head of the legislator”.

Both sides also cited the Monopolies Commission report for their position. While the defendants’ side emphasized that the Monopolies Commission had expressed a negative view of Section 20(3) GWB, the plaintiffs’ side argued that at the same time, unequal treatment of the case constellations was criticized. Both are true, as a look at para 357 of the report shows.

Overall, the Senate, like the Chamber of the Düsseldorf Regional Court, was skeptical of the comparison between selling below production costs of the own product and selling below the price paid to a third-party supplier. In addition to any legislative considerations, the differences in the value chains had to be considered, which are structured more complexly in the constellation of in-house production by retailers. Furthermore, it was increasingly discussed in the hearing that establishing whether a product is sold below production costs involves even greater difficulties of proof than in the case of selling below cost price.

Coffee is a great product to lure consumers into the supermarket. Consumers like to compare coffee prices, especially when coffee prices—as is currently the case—raise one’s pulse like a strong espresso due to poor harvests and other factors. In the present case, Tchibo had conducted comprehensive chemical analyses to demonstrate the manufacturing quality of the affected coffee. For the lay barista, this part of the hearing offered an instructive, albeit brief, excursus on the merits of different bean varieties. However, the sale below production costs was not disputed in this case, which is why this aspect was not substantially addressed. With a view to similar cases, however, a success for Tchibo before the OLG could lead to a wave of further complex procedures.

Tchibo as a Medium-Sized Undertaking?

The last point of contention for the day was the classification of Tchibo as a medium-sized undertaking within the meaning of Section 20(3) GWB. With about €3 billion in worldwide annual sales, this could certainly be questioned. This aspect had been left open by the LG. Presiding Judge Egger described Section 20 GWB in this context as “Section 19 GWB for the protection of the little people” (Section 19 is the German equivalent to Article 102 TFEU).

The plaintiff’s side emphasized that the absolute size of the company could not be decisive. The crucial factor was the relative relationship to Aldi-Süd. Here, the focus should not be on the position in the coffee market, but on the power position in the individual case. A “static view” was wrong. In particular, the possibility of cross-subsidization by Aldi-Süd must be considered. Retailers have a considerably greater scope to offset short-term loss-making transactions with profits from other goods.

Have you checked the 2025 D’Kart Antitrust Advent Calendar? It’s Disszember, and you should not miss this entertaining day-by-day adventure!

Critical Stance of the Court

Overall, a successful appeal by Tchibo seems unlikely. The court has indicated that it considers the existence of several prerequisites to be questionable. Tchibo itself already admitted this. Arnd Liedtke, Tchibo’s company spokesman, commented in a press release: “We regret that the OLG is inclined to this view. The court would thus miss an opportunity to halt a structural aberration in the German food retail trade”.

The political dimension of the proceedings also resonated in the hearing, with the plaintiff’s representatives raising a generally critical fundamental legal-political attitude towards the prohibition of Section 20(3) Sentence 2 No. 1 GWB. The appellants repeatedly emphasized the fundamental importance of the proceedings in this context. The defendant’s side also took up this aspect, stating that “judicial restraint is appropriate”.

It remains to be seen whether the proceedings—regardless of the outcome in Düsseldorf—will continue before the Federal Court of Justice (BGH). The judgment is scheduled to be announced on January 13, 2026.

Klara Dresselhaus is a research associate and doctoral candidate at the Chair of Civil Law, German and European Competition Law at Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf.

If you do not want to miss updates to our blog, subscribe to our newsletter here (and check your spam folder for the confirmation e-mail).

2 thoughts on “Tchibo vs. Aldi-Süd: Coffee Prices in Court”